Key information

Publication type: The London Plan

Publication status: Adopted

Publication date:

Contents

14 sections

Policy D1 London’s form, character and capacity for growth

3.1.1 This Plan provides a policy framework for delivering Good Growth through good design. Part A of this policy sets out the requirements for assessing an area’s characteristics and Part B sets out the steps for using this information to establish the capacity for growth of different areas and ensure that sites are developed to an optimum capacity that is responsive to the site’s context and supporting infrastructure.

3.1.2 Understanding the existing character and context of individual areas is essential in determining how different places may best develop in the future. An evaluation of the current characteristics of a place, how its past social, cultural, physical and environmental influences have shaped it and what the potential opportunities are for it to change will help inform an understanding of an area’s capacity for growth and is crucial for ensuring that growth and development is inclusive.

3.1.3 It is important to understand how places are perceived, experienced and valued. Those involved in commissioning or undertaking area assessments should consider how they can involve the widest range of people appropriate depending on the scope and purpose of the work.

3.1.4 Area assessments should be used to identify the areas that are appropriate for extensive, moderate, or limited growth to accommodate borough-wide growth requirements. This analysis should form the foundation of Development Plan preparation and area-based strategies. This process will be fundamental to inform decision making on how places should develop, speeding up the Development Plan process and bringing about better-quality development. It will also help speed up planning decision making by providing an easily accessible knowledge-base about an area that is integrated in Development Plan policies.

3.1.5 When identifying the growth potential of areas and sites the sequential spatial approach to making the best use of land set out in GG2 Parts A to C should be followed.

3.1.6 The process set out in this policy, of evidence gathering and establishing the location and scale of growth in an area, provides the opportunity to engage and collaborate with the local community and other stakeholders as part of the plan making process, enabling them to help shape their surroundings. The requirements of Parts A and B help to inform the identification of locations that may be suitable for tall buildings, see Policy D9 Tall buildings.

3.1.7 As change is a fundamental characteristic of London, respecting character and accommodating change should not be seen as mutually exclusive. Understanding of the character of a place should not seek to preserve things in a static way but should ensure an appropriate balance is struck between existing fabric and any proposed change. Opportunities for change and transformation, through new building forms and typologies, should be informed by an understanding of a place’s distinctive character, recognising that not all elements of a place are special and valued.

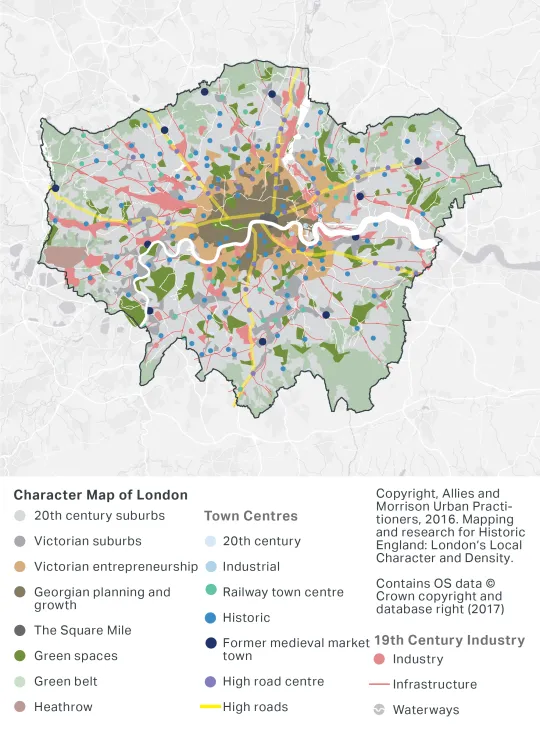

3.1.8 The Mayor will provide supplementary planning guidance to provide additional support for boroughs when implementing the policy. Figure 3.1 illustrates the broad characteristics of London as derived from its historical development, which can be used to inform area-based strategies.

Figure 3.1 - Outline Character Map of London

Policy D2 Infrastructure requirements for sustainable densities

3.2.1 Infrastructure provision should be proportionate to the scale of development. The locations and scale of growth will be identified through boroughs’ Development Plans, particularly through site allocations. Infrastructure capacity, having regard to the growth identified in the Development Plan, should be identified in boroughs’ infrastructure delivery plans or programmes. Boroughs and infrastructure providers should also consider the cumulative impact of multiple development proposals in an area.

3.2.2 If development comes forward with a capacity in excess of that which could be supported by current or future planned infrastructure, a site-specific infrastructure assessment will be required. This assessment should establish what additional impact the proposed development will have on current and planned infrastructure, and how this can be appropriately mitigated either on the site, or through an off-site mechanism, having regard to the amount of CIL generated.

3.2.3 The capacity of existing and future public transport services, and the connections they provide, should be taken into consideration, as should the potential to increase this capacity through financial contributions and by joint working with Transport for London. In general, the higher the public transport access and connectivity of the site, and the closer it is to a town centre or station, the higher the density and the lower the car parking provision should be. The ability to support higher densities through encouraging increased levels of active travel should be taken into account.

3.2.4 Minor developments will typically have incremental impacts on local infrastructure capacity. The cumulative demands on infrastructure of minor development should be addressed in boroughs’ infrastructure delivery plans or programmes. Therefore, it will not normally be necessary for minor developments to undertake infrastructure assessments or for boroughs to refuse permission to these schemes on the grounds of infrastructure capacity.

3.2.5 In certain circumstances, development will be contingent on the future provision of public transport, walking and cycling infrastructure. In many areas of London higher densities could be supported by maximising the potential of active travel. Those limited circumstances for which Part B of the policy could apply include development being brought forward in areas where planned public transport schemes will significantly improve accessibility and capacity of an area, such as Crossrail 2, DLR extensions, extension of the Elizabeth line, and the Bakerloo line Extension. It may be necessary to require the phasing of development proposals to maximise the benefits from major infrastructure and services investment whilst avoiding any unacceptable impacts on existing infrastructure prior to the new capacity being available.

3.2.6 In order to support the Healthy Streets Approach, development proposals should take account of the existing and planned connectivity of a site via public transport and active modes to town centres, social infrastructure and other services and places of employment. Opportunities to improve these connections to support higher density development should be identified.

Policy D3 Optimising site capacity through the design-led approach

3.3.1 For London to accommodate the growth identified in this Plan in an inclusive and responsible way every new development needs to make the most efficient use of land by optimising site capacity. This means ensuring the development’s form is the most appropriate for the site and land uses meet identified needs. The optimum capacity for a site does not mean the maximum capacity; it may be that a lower density development – such as gypsy and traveller pitches – is the optimum development for the site.

3.3.2 A design-led approach to optimising site capacity should be based on an evaluation of the site’s attributes, its surrounding context and its capacity for growth to determine the appropriate form of development for that site.

3.3.3 The area assessment required by Part A of Policy D1 London’s form, character and capacity for growth, coupled with an area’s assessed capacity for growth as required by Part B of Policy D1 London’s form, character and capacity for growth, will assist in understanding a site’s context and determining what form of development is most appropriate for a site. Design options for the site should be assessed to ensure the proposed development best delivers the design outcomes in Part D of this policy.

3.3.4 Designating appropriate development capacities through site allocations enables boroughs to proactively optimise the capacity of strategic sites through a consultative design-led approach that allows for meaningful engagement and collaboration with local communities, organisations and businesses.

3.3.5 Developers should have regard to designated development capacities in allocated sites and ensure that the design-led approach to optimising capacity on unallocated sites is carefully applied when formulating bids for development sites. The sum paid for a development site is not a relevant consideration in determining acceptable densities and any overpayments cannot be recouped through compromised design or reduced planning obligations.

3.3.6 Good design and good planning are intrinsically linked. The form and character of London’s buildings and spaces must be appropriate for their location, fit for purpose, respond to changing needs of Londoners, be inclusive, and make the best use the city’s finite supply of land. The efficient use of land requires optimisation of density. This means coordinating the layout of the development with the form and scale of the buildings and the location of the different land uses, and facilitating convenient pedestrian connectivity to activities and services.

3.3.7 Developments that show a clear understanding of, and relationship with, the distinctive features of a place are more likely to be successful. These features include buildings, structures, open spaces, public realm and the underlying landscape. Development should be designed to respond to the special characteristics of these features which can include: predominant architectural styles and/or building materials; architectural rhythm; distribution of building forms and heights; and heritage, architectural or cultural value. The Mayor will provide further guidance on assessing and optimising site capacity through a design led approach.

3.3.8 Buildings should be of high quality and enhance, activate and appropriately frame the public realm. Their massing, scale and layout should help make public spaces coherent and should complement the existing streetscape and surrounding area. Particular attention should be paid to the design of the parts of a building or public realm that people most frequently see or interact with in terms of its legibility, use, detailing, materials and location of entrances. Creating a comfortable pedestrian environment with regard to levels of sunlight, shade, wind, and shelter from precipitation is important.

3.3.9 Measures to design out exposure to poor air quality and noise from both external and internal sources should be integral to development proposals and be considered early in the design process. Characteristics that increase pollutant or noise levels, such as poorly-located emission sources, street canyons and noise sources should also be designed out wherever possible. Optimising site layout and building design can also reduce the risk of overheating as well as minimising carbon emissions by reducing energy demand.

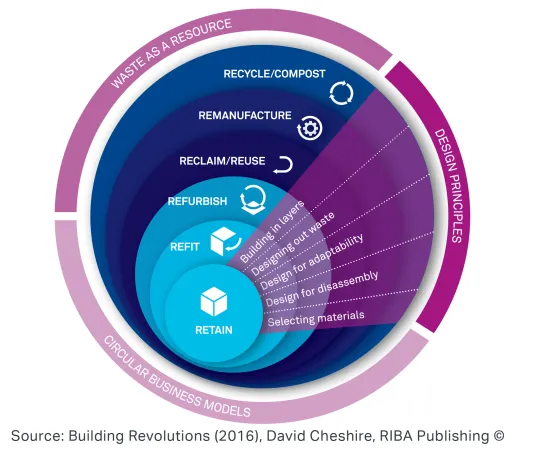

3.3.10 To minimise the use of new materials, the following circular economy principles (see also Figure 3.2) should be taken into account at the start of the design process and, for referable applications or where a lower local threshold has been established, be set out in a Circular Economy Statement (see Policy SI 7 Reducing waste and supporting the circular economy):

- building in layers – ensuring that different parts of the building are accessible and can be maintained and replaced where necessary

- designing out waste – ensuring that waste reduction is planned in from project inception to completion, including consideration of standardised components, modular build and re-use of secondary products and materials

- designing for longevity

- designing for adaptability or flexibility

- designing for disassembly

- using systems, elements or materials that can be re-used and recycled.

3.3.11 Large-scale developments in particular present opportunities for innovative building design that avoids waste, supports high recycling rates and helps London transition to a circular economy, where materials, products and assets are kept at their highest value for as long as possible. Further guidance on the application of these principles through Circular Economy Statements will be provided.

3.3.12 Figure 3.2 shows a hierarchy for building approaches which maximises use of existing materials. Diminishing returns are gained by moving through the hierarchy outwards, working through refurbishment and re-use through to the least preferable option of recycling materials produced by the building or demolition process. The best use of the land needs to be taken into consideration when deciding whether to retain existing buildings in a development.

3.3.13 Maximising urban greening and creating green open spaces provides attractive places for Londoners to relax and play, and helps make the city more resilient to the effects of climate change. Landscaping and urban greening should be designed to ecologically enhance and, where possible, physically connect, existing parks and open spaces.

3.3.14 Measures to design out crime should be integral to development proposals and be considered early in the design process. Development should reduce opportunities for anti-social behaviour, criminal activities, and terrorism, and contribute to a sense of safety without being overbearing or intimidating. Developments should ensure good natural surveillance, clear sight lines, appropriate lighting, logical and well-used routes and a lack of potential hiding places.

3.3.15 Development should create inclusive places that meet the needs of all potential users.

3.3.16 The design and layout of development should reduce the dominance of cars and provide permeability to support active travel (public transport, walking and cycling), community interaction and economic vitality.

Figure 3.2 - Circular economy hierarchy for building approaches

3.3.17 New developments should be designed and managed so that deliveries can be received outside of peak hours and if necessary in the evening or night-time without causing unacceptable nuisance to residents. Appropriate facilities will be required to minimise additional freight trips arising from missed deliveries.

3.3.18 Shared and easily accessible storage space supporting separate collection of dry recyclables, food waste and other waste should be considered in the early design stages to help improve recycling rates, reduce smell, odour and vehicle movements, and improve street scene and community safety.

3.3.19 Buildings and spaces should be designed so that they can adapt to changing uses and demands now and in the future. Their lifespan and potential uses or requirements should be carefully considered, creating buildings and spaces that are easy to maintain, and constructed of materials that are safe, robust and remain attractive over time.

3.3.20 Masterplans and strategic frameworks should be used when planning large-scale development to create welcoming and inclusive neighbourhoods, promote active travel, enable the successful integration of the built form within its surrounding area, and deliver wider benefits to residents, such as access to shared amenity space and high-quality public realm.

Monitoring density and site capacity

3.3.21 Comparing density between schemes using a single measure can be misleading as it is heavily dependent on the area included in the planning application site boundary as well as the size of residential units. Planning application boundaries are determined by the applicant. These boundaries may be drawn very close to the proposed buildings, missing out adjacent areas of open space, which results in a density which belies the real character of a scheme. Alternatively, the application boundary may include a large site area so that a tall building appears to be a relatively low-density scheme while its physical form is more akin to schemes with a much higher density.

3.3.22 To help assess, monitor and compare development proposals several measures of density are required to be provided by the applicant. Density measures related to the residential population will be relevant for infrastructure provision, while measures of density related to the built form and massing will inform its integration with the surrounding context. The following measurements of density should be provided for all planning applications that include new residential units:

- number of units per hectare

- number of habitable rooms per hectare

- number of bedrooms per hectare

- number of bedspaces per hectare.

3.3.23 Measures relating to height and scale should be the maximum height of each building or major component in the development. Boroughs should report each of the required density measures provided by the applicant when they submit details of the development to the London Development Database. The following additional measurements should be provided for all major planning applications:

- the Floor Area Ratio (total Gross External Area of all floors / site area)

- the Site Coverage Ratio (Gross External Area of ground floors /site area)

- the maximum height in metres above ground level of each building and at Above Ordinance Datum (above sea level).

Policy D4 Delivering good design

3.4.1 The processes and actions set out in the policy will help ensure development delivers good design. The responsibility for undertaking a particular process or action will depend on the nature of the development or plan; however, the outcome of this process must ensure the most efficient use of land is made so that the development on all sites is optimised.

3.4.2 Applicants will primarily be responsible for undertaking design analysis through the use of various digital modelling techniques as part of a wide range of design and presentation techniques. These techniques can also be used as part of the plan-making process to assess growth options and forms of development, as described in Part B of Policy D1 London’s form, character and capacity for growth.

3.4.3 To enable the design of a proposed development to be fully assessed, applicants must provide the necessary technical information in an agreed format. The detail and nature of this should be commensurate with the scale of the development. All outline applications referred to the Mayor should be accompanied by thorough design codes, ensuring exemplary design standards are carried through the planning process to completion.

3.4.4 The Mayor’s Design Advocates (MDAs) will play a key role in helping to deliver good design. They will help champion design across the GLA Group and beyond, through research, design review, capacity building, commissioning and advocacy. MDAs are also members of the London Review Panel, which the Mayor has set up to provide design scrutiny. This review panel is primarily focused on the review of Mayoral investments, but can provide design review sessions for development proposals referred to the Mayor where they have not previously been subject to review, or for schemes of particular significance.

3.4.5 All development proposals should be subject to a level of scrutiny appropriate to the scale and/or impact of the project. This design scrutiny should include work by planning case officers and ongoing and informal review by qualified urban design officers and conservation officers. Development proposals required to undergo design review as set out under Part D will form a small portion of overall planning applications in London. The Mayor may require that other referable developments undergo design review. Boroughs are encouraged to use design review to support their scrutiny of development proposals.

3.4.6 The Mayor has published a London Quality Review Charter, with accompanying guidance. The Charter promotes a consistent approach across London’s design review sector and promotes transparency of process. The Charter builds on the established 2013 guidance[27] which calls for reviews to be independent, expert, multidisciplinary, accountable, transparent, proportionate, timely, advisory, objective and available. The Charter includes guidance on how panels and processes should be managed and records kept. It also clarifies that the purpose of the design review process is not to dictate the design of a scheme or contradict planning policy, but to guide better design outcomes. More widely, the Mayor’s Good Growth by Design Programme, is developing a support offer to London’s boroughs and London’s review sector, for example, offering advice to boroughs wishing to put in place a design review function.

3.4.7 The scrutiny of a proposed development’s design should cover its layout, scale, height, density, land uses, materials, architectural treatment, detailing and landscaping. The design and access statement should explain the approach taken to these design issues (see also requirements of Policy D5 Inclusive design).

3.4.8 For residential development it is particularly important to scrutinise the qualitative aspects of the development design described in Policy D6 Housing quality and standards. The higher the density of a development the greater this scrutiny should be of the proposed built form, massing, site layout, external spaces, internal design and ongoing management. This is important because these elements of the development come under more pressure as the density increases. The housing minimum space standards set out in Policy D6 Housing quality and standards help ensure that as densities increase, quality of internal residential units is maintained.

3.4.9 Higher density residential developments[28] should demonstrate their on-going sustainability in terms of servicing, maintenance and management. Specifically, details should be provided of day-to-day servicing and deliveries, longer-term maintenance implications and the long-term affordability of running costs and service charges (by different types of occupiers).

3.4.10 It is important that design quality is maintained throughout the development process from the granting of planning permission to completion of a development. What happens to a design after planning consent can be instrumental to the success of a project and subsequent quality of a place. Changes to designs after the initial planning permission has been granted are often allowable as minor amendments, or in the case of outline applications in the form of additional necessary detail. However, even minor changes can have a substantial effect on design quality, environmental quality and visual impact. The cumulative effect of amendments can often be significant and should be reviewed holistically. Sufficient design detail needs to be provided in approved drawings and other visual material, as well as in the wording of planning permissions to ensure clarity over what design has been approved, and to avoid future amendments and value engineering resulting in changes that would be detrimental to the design quality.

3.4.11 Design codes submitted with outline planning applications for large developments can be one such way to ensure that design quality is upheld throughout the planning process. Their main purpose is to describe the key design principles of a development proposal in a simple, concise and mainly graphical format, and they should draw on the proposal’s layout, massing and heights to define the principal features that make up the overall design integrity of the scheme. Assessment of the design of large elements of a development, such as landscaping or building façades, should be undertaken as part of assessing the whole development and not deferred for consideration after planning permission has been granted.

3.4.12 Having a sufficient level of design information, including key construction details provided as part of the application, can help to ensure that the quality of design will be maintained if the permitted scheme is subject to subsequent minor amendments. However, it is also generally beneficial to the design quality of a completed development if the architectural design team is involved in the development from start to finish.[29]Securing the design team’s ongoing involvement can be achieved in a number of ways, such as through a condition of planning permission, as a design reviewer, or through an architect retention clause in a legal agreement.

Policy D5 Inclusive design

3.5.1 The built environment includes the internal and external parts of buildings, as well as the spaces in between them. Despite recent progress in building a more accessible city, too many Londoners still experience barriers to living independent and dignified lives, due to the way the built environment has been designed and constructed or how it is managed. An inclusive design approach helps to ensure the diverse needs of all Londoners are integrated into Development Plans and proposals from the outset. This is essential to ensuring that the built environment is safe, accessible and convenient, and enables everyone to access the opportunities London has to offer.

3.5.2 Inclusive design is indivisible from good design. It is therefore essential to consider inclusive design and the development’s contribution to the creation of inclusive neighbourhoods at the earliest possible stage in the development process – from initial conception through to completion and, where relevant, the occupation and on-going management and maintenance of the development.

3.5.3 Inclusive design principles should be discussed with boroughs in advance of an application being submitted, to ensure that these principles are understood and incorporated into the original design concept. To demonstrate this, and to inform decision making, speed up the process and bring about better-quality development, an inclusive design statement is required as part of the Design and Access Statement. The inclusive design statement should:

- explain the design concept and illustrate how an inclusive design approach has been incorporated into this

- detail what best practice standards and design guidance documents have been applied in terms of inclusive design

- show that the potential impacts of the proposal on people and communities who share a protected characteristic and who will be affected by it have been considered

- set out how access and inclusion will be maintained and managed, including fire evacuation procedures

- detail engagement with relevant user groups, such as disabled or older people’s organisations, or other equality groups.

3.5.4 The detail contained in the Design and Access Statements, including the inclusive design statement, should be proportionate to the scale and type of development.

3.5.5 The social factors that influence inclusion have a direct impact on well-being and are an important component in achieving more inclusive communities. Many factors that influence potential barriers to inclusion can be mitigated by ensuring the involvement of local communities in the planning policies and decisions that will affect them.

3.5.6 Inclusive design creates spaces and places that can facilitate social integration, enabling people to lead more interconnected lives. Development proposals should help to create inclusive neighbourhoods that cumulatively form a network in which people can live and work in a safe, healthy, supportive and inclusive environment. An inclusive neighbourhood approach will ensure that people are able to easily access services, facilities and amenities that are relevant to them and enable them to safely and easily move around by active travel modes through high-quality, people-focused spaces, while enjoying barrier-free access to surrounding areas and the wider city.

3.5.7 Links to the wider neighbourhood should be carefully considered, including networks of legible, logical, safe and navigable pedestrian routes, dropped kerbs and crossing points with associated tactile paving.

3.5.8 Where security measures are required in the external environment, the design and positioning of these should not adversely impact access and inclusion.

3.5.9 Entrances into buildings should be easily identifiable and should allow everyone to use them independently without additional effort, separation or special treatment. High and low level obstructions in buildings and in the public realm should be eliminated. The internal environment of developments should meet the highest standards in terms of access and inclusion, creating buildings which meet the needs of the existing and future population.

3.5.10 Buildings should be designed and built to accommodate robust emergency evacuation procedures for all building users, including those who require level access. All building users should be able to evacuate from a building with dignity and by as independent means as possible. Emergency carry down or carry up mechanical devices or similar interventions that rely on manual handling are not considered to be appropriate, for reasons of user dignity and independence. The installation of lifts which can be used for evacuation purposes (accompanied by a management plan) provide a dignified and more independent solution. The fire evacuation lifts and associated provisions should be appropriately designed, constructed and include the necessary controls suitable for the purposes intended. See also Policy D12 Fire safety.

3.5.11 When dealing with historic buildings and heritage assets, careful consideration should be given to inclusive design at an early stage. This is essential to securing successful schemes that will enable as many people as possible to access and enjoy the historic environment now and in the future.

3.5.12 The Mayor will assist boroughs and other agencies in implementing an inclusive design approach by providing further guidance where necessary, continuing to contribute to the development of national technical standards and supporting training and professional development programmes. Further guidance on inclusive design standards can be found in the following British Standard documents:

- BS8300-1:2018 Design of an accessible and inclusive built environment. External environment. Code of practice. January 2018

- BS8300-2:2018 Design of an accessible and inclusive built environment. Buildings. Code of practice. January 2018.

Policy D6 Housing quality and standards

F Housing developments are required to meet the minimum standards below which apply to all tenures and all residential accommodation that is self-contained.

Private internal space

1) Dwellings must provide at least the gross internal floor area and built-in storage area set out in Table 3.1.

2) A dwelling with two or more bedspaces must have at least one double (or twin) bedroom that is at least 2.75m wide. Every other additional double (or twin) bedroom must be at least 2.55m wide.

3) A one bedspace single bedroom must have a floor area of at least 7.5 sq.m. and be at least 2.15m wide.

4) A two bedspace double (or twin) bedroom must have a floor area of at least 11.5 sq.m..

5) Any area with a headroom of less than 1.5m is not counted within the Gross Internal Area unless used solely for storage (If the area under the stairs is to be used for storage, assume a general floor area of 1 sq.m. within the Gross Internal Area).

6) Any other area that is used solely for storage and has a headroom of 0.9-1.5m (such as under eaves) can only be counted up to 50 per cent of its floor area, and any area lower than 0.9m is not counted at all.

7) A built-in wardrobe counts towards the Gross Internal Area and bedroom floor area requirements, but should not reduce the effective width of the room below the minimum widths set out above. Any built-in area in excess of 0.72 sq.m. in a double bedroom and 0.36 sq.m. in a single bedroom counts towards the built-in storage requirement.

8) The minimum floor to ceiling height must be 2.5m for at least 75 per cent of the Gross Internal Area of each dwelling.

Private outside space

9) Where there are no higher local standards in the borough Development Plan Documents, a minimum of 5 sq.m. of private outdoor space should be provided for 1-2 person dwellings and an extra 1 sq.m. should be provided for each additional occupant, and it must achieve a minimum depth and width of 1.5m. This does not count towards the minimum Gross Internal Area space standards required in Table 3.1

G The Mayor will produce guidance on the implementation of this policy for all housing tenures.

Table 3.1 - Minimum internal space standards for new dwellings

Minimum gross internal floor areas and storage in square metres

Notes to Table 3.1

Key

b: bedrooms

p: persons

New dwelling in this context includes new build, conversions and change of use.

* Where a studio / one single bedroom one person dwelling has a shower room instead of a bathroom, the floor area may be reduced from 39 sq.m. to 37 sq.m., as shown bracketed.

The Gross Internal Area (GIA) of a dwelling is defined as the total floor space measured between the internal faces of perimeter walls that enclose a dwelling. This includes partitions, structural elements, cupboards, ducts, flights of stairs and voids above stairs. GIA should be measured and denoted in square metres (sq.m.).

Built-in storage areas are included within the overall GIA and include an allowance of 0.5 sq.m. for fixed services or equipment such as a hot water cylinder, boiler or heat exchanger.

GIAs for one storey dwellings include enough space for one bathroom and one additional WC (or shower room) in dwellings with five or more bedspaces. GIAs for two and three storey dwellings include enough space for one bathroom and one additional WC (or shower room). Additional sanitary facilities may be included without increasing the GIA, provided that all aspects of the space standard have been met.

3.6.1 Housing can be delivered in different physical forms depending on the context and site characteristics. Ensuring homes are of adequate size and fit for purpose is crucial in an increasingly dense city; therefore this Plan sets out minimum space standards for dwellings of different sizes in Policy D6 Housing quality and standards and Table 3.1. This is based on the minimum gross internal floor area (GIA) relative to the number of occupants and takes into account commonly required furniture and the spaces needed for different activities and moving around. This means applicants should state the number of bedspaces/ occupiers a home is designed to accommodate rather than simply the number of bedrooms. When designing homes for more than eight bedspaces, applicants should allow approximately 10 sq.m. per extra bedspace.

3.6.2 The space standards are minimums which applicants are encouraged to exceed. The standards apply to all new self-contained dwellings of any tenure, and consideration should be given to the elements that enable a home to become a comfortable place of retreat. The provision of additional services and spaces as part of a housing development, such as building management and communal amenity space, is not a justification for failing to deliver these minimum standards. Boroughs are, however, encouraged to resist dwellings with floor areas significantly above those set out in Table 3.1 for the number of bedspaces they contain due to the level of housing need and the need to make efficient use of land.

3.6.3 To address the impacts of the urban heat island effect and the fact that the majority of housing developments in London are made up of flats, a minimum ceiling height of 2.5m for at least 75 per cent of the gross internal area is required so that new housing is of adequate quality, especially in terms of daylight penetration, ventilation and cooling, and sense of space. The height of ceilings, doorways and other thresholds should support the creation of an inclusive environment and therefore be sufficiently high to not cause an obstruction. To allow for some essential equipment in the ceilings of kitchens and bathrooms, up to 25 per cent of the gross internal area of the dwelling can be lower than 2.5 m. However, any reduction in ceiling height below 2.5 m should be the minimum necessary for this equipment, and not cause an obstruction.

3.6.4 Dual aspect dwellings with opening windows on at least two sides have many inherent benefits. These include better daylight, a greater chance of direct sunlight for longer periods, natural cross-ventilation, a greater capacity to address overheating, pollution mitigation, a choice of views, access to a quiet side of the building, greater flexibility in the use of rooms, and more potential for future adaptability by altering the use of rooms.

3.6.5 Single aspect dwellings are more difficult to ventilate naturally and are more likely to overheat, and therefore should normally be avoided. Single aspect dwellings that are north facing, contain three or more bedrooms or are exposed to noise levels above which significant adverse effects on health and quality of life occur, should be avoided. The design of single aspect dwellings must demonstrate that all habitable rooms and the kitchen are provided with adequate passive ventilation, privacy and daylight, and that the orientation enhances amenity, including views. It must also demonstrate how they will avoid overheating without reliance on energy intensive mechanical cooling systems.

3.6.6 A variety of approaches to housing typologies and layout of buildings should be explored to make the best use of land and create high quality, comfortable and attractive homes. For example, increasing ceiling heights and having bay windows can optimise daylight and sunlight and allow buildings to be closer together than can otherwise be achieved.

3.6.7 Housing developments should be designed to maximise tenure integration, and affordable housing units should have the same external appearance as private housing. All entrances will need to be well integrated with the rest of the development and should be indistinguishable from each other.

3.6.8 Development should help create a more socially inclusive London. Gated forms of development that could realistically be provided as a public street are unacceptable and alternative means of security should be achieved through utilising the principles of good urban design and inclusive design (see Policy D5 Inclusive design).

3.6.9 Private outside space should be practical in terms of its shape and utility, and care should be taken to ensure the space offers good amenity. All dwellings should have level access to one or more of the following forms of private outside spaces: a garden, terrace, roof garden, courtyard garden or balcony. The use of roof areas, including podiums, and courtyards for additional private or shared outside space is encouraged.

3.6.10 Communal play space should meet the requirements of Policy S4 Play and informal recreation.

Table 3.2 Qualitative design aspects to be addressed in housing developments

* See also the London Waste and Recycling Board’s Waste Management Planning Advice for New Flatted Properties 2014. http://www.lwarb.gov.uk/what-we-do/resource-london/successes-to-date/efficiencies-programme-outputs/

3.6.10 Other components of housing design are also important to improving the attractiveness of new homes as well as the Mayor’s wider objectives to improve the quality of Londoners’ environment. The Mayor intends to produce a single guidance document which clearly sets out the standards which need to be met in order to implement Policy D6 Housing quality and standards for all housing tenures, as well as wider qualitative aspects of housing developments. This will include guidance on daylight and sunlight standards. This will build on the guidance set out in the 2016 Housing SPG and the previous London Housing Design Guide.

Policy D7 Accessible housing

3.7.1 Many households in London require accessible or adapted housing to lead dignified and independent lives. In addition, Londoners are living longer and with the incidence of disability increasing with age, older people should have the choice of remaining in their own homes rather than moving due to inaccessible accommodation. To address these and future needs, Policy D7 Accessible housing should apply to all dwellings which are created via works to which Part M volume 1 of the Building Regulations applies,[30] which, at the time of publication of this Plan, generally limits the application of this policy to new build dwellings.

3.7.2 Where any part of an approach route – including the vertical circulation in the common parts of a block of flats – is shared between dwellings of different categories (i.e. M4(2) and M4(3)), the design provisions of the highest numbered category of dwelling served should be applied, to ensure that people can visit their neighbours with ease and are not limited by the design of communal areas. For residential disabled persons parking requirements – see Policy T6 .1 Residential parking.

3.7.3 To ensure that all potential residents have choice within a development, the requirement for M4(3) wheelchair user dwellings applies to all tenures. Wheelchair user dwellings should be distributed throughout a development to provide a range of aspects, floor level locations, views and unit sizes.

3.7.4 Standard M4(3) wheelchair user dwellings distinguishes between ‘wheelchair accessible’ (a home readily usable by a wheelchair user at the point of completion) and ‘wheelchair adaptable’ (a home that can be easily adapted to meet the needs of a wheelchair user). Planning Practice Guidance[31] states that Local Plan policies for wheelchair accessible homes should only be applied to those dwellings where the local authority is responsible for allocating or nominating a person to live in that dwelling, otherwise M4(3) dwellings should be wheelchair adaptable.

3.7.5 As set out in Approved Document M of the Building Regulations, Volume 1: Dwellings, to comply with requirements M4(2) or M4(3), step-free access into the dwelling must be provided.

3.7.6 In exceptional circumstances the provision of a lift to dwelling entrances may not be achievable. In the following circumstances – and only in blocks of four storeys or less – it may be necessary to apply some flexibility in the application of this policy:

- Specific small-scale infill developments (see Policy H2 Small sites)

- Flats above existing shops or garages

- Stacked maisonettes where the potential for decked access to lifts is restricted

3.7.7 If it is agreed at the planning stage (for one of the reasons listed above) that a specific development warrants flexibility in the application of the accessible housing standards M4(2) and M4(3), affected dwellings above or below ground floor would be required to satisfy the mandatory building regulations requirements of M4(1) via the Building Control process. M4(2) and M4(3) dwellings should still be required for ground floor units.

3.7.8 M4(2) and M4(3) dwellings should be secured via planning condition to allow the Building Control body to check compliance of a development against the optional Building Regulations standards. Planning conditions should specify:

- Number of dwellings per size typology (i.e. x no. of y bed units) which must comply with Part M4(2)

- Number of dwellings per size typology (i.e. x no. of y bed units) which must comply with Part M4(3)(2)(a) wheelchair adaptable standards

- Number of dwellings per size typology (i.e. x no. of y bed units) which must comply with Part M4(3)(2)(b) wheelchair accessible standards,

Policy D8 Public realm

3.8.1 The public realm includes all the publicly-accessible space between buildings, whether public or privately owned, from alleyways and streets to squares and open spaces, including the Thames and London’s waterways. Some internal or elevated spaces can also be considered as part of the public realm, such as markets, shopping malls, sky gardens, viewing platforms, museums or station concourses. Such forms of public realm are particularly relevant in areas of higher density.

3.8.2 The quality of the public realm has a significant influence on quality of life because it affects people’s sense of place, security and belonging, as well as having an influence on a range of health and social factors. For this reason, the public realm, and the buildings that frame those spaces, should be attractive, accessible, designed for people and contribute to the highest possible standards of comfort, good acoustic design, security and ease of movement. Higher levels of comfort should be sought in places where people will wish to sit, play, relax, meet, and dwell outside compared to other parts of the public realm that are primarily used for movement. As London’s population grows, the demands on London’s public realm to accommodate a greater variety and intensity of uses will increase. It is particularly important to recognise these demands in higher density development.

3.8.3 The public realm should be seen as a series of connected routes and spaces that help to define the character of a place. Around eighty per cent of public realm in London is in the form of streets and roads. A small proportion (less than eight per cent) of these have the primary purpose of moving large numbers of vehicles through them, while most are intended to be quiet residential streets used for play, recreation and local access. The remaining streets are places which function as key centres for leisure, shopping, culture, social interaction and accessing services and employment, such as high streets or public squares.

3.8.4 The specific balance between the different functions of any one space, such as its place-based activities, its function to facilitate movement and its ability to accommodate different uses of the kerbside, should be at the heart of how the space is designed and managed. The Mayor’s Healthy Streets Approach explains how the design and management of streets can support a wide range of activities in the public realm as well as encourage and facilitate a shift to active travel.

3.8.5 Pedestrian crossings should be accessible and provide tactile paving and associated dropped kerbs or level access in accordance with national guidance.

3.8.6 Places should be distinctive, attractive and of the highest quality, allowing people to meet, congregate and socialise, as well as providing opportunity for quiet enjoyment. Public realm is valuable for London’s cultural activity, providing a stage for informal and everyday culture and for organised cultural activity. The opportunity to incorporate these uses should be identified and facilitated through community engagement, careful design and good acoustic design. Careful consideration is needed of the benefits of using the public realm for particular events and the impact of the events on the use and enjoyment of the space by the public.

3.8.7 Legibility and signposting make an important contribution to whether people feel comfortable in a place, and are able to understand it and navigate their way around. Transport for London’s Streets Toolkit provides detailed design guidance for creating high quality streets and public spaces.

3.8.8 Even when a development does not include the creation of new public realm it will have an impact on neighbouring public realm. Therefore, any impact or change to the conditions, use or nature of existing public space brought about by a development should meet the requirements of this policy.

3.8.9 The effective management and ongoing maintenance of public realm should be a key consideration in the design of places and secured through the planning system where appropriate. Whether publicly or privately owned, public realm should be open, free to use and offer the highest level of public access. These spaces should only have rules restricting the behaviour of the public that are considered essential for safe management of the space. The Mayor will develop a ‘Public London Charter’ which will set out the rights and responsibilities for the users, owners and managers of public spaces irrespective of land ownership. The rules and restrictions on public access and behaviour covering all new or redeveloped public space and its management should be in accordance with the Public London Charter, and this requirement should be secured through legal agreement or planning condition.

3.8.10 The lighting of the public realm needs careful consideration to ensure it is appropriate to address safety and security issues, and make night-time activity areas and access routes welcoming and safe, while also minimising light pollution.

3.8.11 The provision of accessible free drinking water fountains helps improve public health, reduces waste from single-use plastic bottles and supports the circular economy through the use of reusable water bottles. Free drinking water fountains that can both refill water bottles directly and be drunk from should be provided in appropriate locations in new or redeveloped public realm. Appropriate locations for these water fountains should be identified by boroughs during the planning process. These locations include areas with high levels of pedestrian activity, such as in town centres and inside shopping malls, as well as areas of the public realm used for play, exercise and relaxing, such as parks and squares. The ongoing management and maintenance of facilities should be secured and agreed at the planning stage to ensure long-term provision is achievable.

3.8.12 Opportunities should be identified by boroughs and applicants for the meanwhile (temporary) use of phased development sites to create attractive public realm. Parameters for any meanwhile use, particularly its longevity and associated obligations, should be established from the outset and agreed by all parties. Whilst the creation of temporary public realm makes the best use of land and provides visual, environmental and health benefits to the local community, planning permission for more permanent uses is still required.

Policy D9 Tall buildings

3.9.1 Whilst high density does not need to imply high rise, tall buildings can form part of a plan-led approach to facilitating regeneration opportunities and managing future growth, contributing to new homes and economic growth, particularly in order to make optimal use of the capacity of sites which are well-connected by public transport and have good access to services and amenities. Tall buildings can help people navigate through the city by providing reference points and emphasising the hierarchy of a place such as its main centres of activity, and important street junctions and transport interchanges. Tall buildings that are of exemplary architectural quality, in the right place, can make a positive contribution to London’s cityscape, and many tall buildings have become a valued part of London’s identity. However, they can also have detrimental visual, functional and environmental impacts if in inappropriate locations and/or of poor quality design. The processes set out below will enable boroughs to identify locations where tall buildings play a positive role in shaping the character of an area.

3.9.2 Boroughs should determine and identify locations where tall buildings may be an appropriate form of development by undertaking the steps below:

- based on the areas identified for growth as part of Policy D1 London’s form, character and capacity for growth, undertake a sieving exercise by assessing potential visual and cumulative impacts to consider whether there are locations where tall buildings could have a role in contributing to the emerging character and vision for a place

- in these locations, determine the maximum height that could be acceptable

- identify these locations and heights on maps in Development Plans.

3.9.3 Tall buildings are generally those that are substantially taller than their surroundings and cause a significant change to the skyline. Boroughs should define what is a ‘tall building’ for specific localities, however this definition should not be less than 6 storeys or 18 metres measured from ground to the floor level of the uppermost storey. This does not mean that all buildings up to this height are automatically acceptable, such proposals will still need to be assessed in the context of other planning policies, by the boroughs in the usual way, to ensure that they are appropriate for their location and do not lead to unacceptable impacts on the local area. In large areas of extensive change, such as Opportunity Areas, the threshold for what constitutes a tall building should relate to the evolving (not just the existing) context. This policy applies to tall buildings as defined by the borough. Where there is no local definition, the policy applies to buildings over 6 storeys or 18 metres measured from ground to the floor level of the uppermost storey.

3.9.4 The higher the building the greater the level of scrutiny that is required of its design. In addition, tall buildings that are referable to the Mayor, must be subject to the particular design scrutiny requirements set out in Part D of Policy D4 Delivering good design.

3.9.5 The Mayor will work with boroughs to provide a strategic overview of tall building locations across London and will seek to utilise 3D virtual reality digital modelling to help identify these areas, assess tall building proposals and aid public consultation and engagement. 3D virtual reality modelling can also help assess cumulative impacts of developments, particularly those permitted but not yet completed.

3.9.6 A tall building can be considered to be made up of three main parts: a top, middle and base. The top includes the upper floors, and roof-top mechanical or telecommunications equipment and amenity space. The top should be designed to make a positive contribution to the quality and character of the skyline, and mechanical and telecommunications equipment must be integrated in the total building design. Not all tall buildings need to be iconic landmarks and the design of the top of the building (i.e. the form, profile and materiality) should relate to the building’s role within the existing context of London’s skyline. Where publicly-accessible areas, including viewing areas on upper floors, are provided as a public benefit of the development, they should be freely accessible and in accordance with Part G of Policy D8 Public realm. Well-designed safety measures should be integrated into the design of tall buildings and must ensure personal safety at height.

3.9.7 The middle of a tall building has an important effect on how much sky is visible from surrounding streets and buildings, as well as on wind flow, privacy and the amount of sunlight and shadowing there is in the public realm and by surrounding properties.

3.9.8 The base of the tall building is its lower storeys. The function of the base should be to frame the public realm and streetscape, articulate entrances, and help create an attractive and lively public realm which provides a safe, inclusive, interesting, and comfortable pedestrian experience. The base should integrate with the street frontage of adjacent buildings and, where appropriate, enable the building to transition down in height.

3.9.9 Any external lighting for tall buildings should be minimal, energy efficient and designed to minimise glare, light trespass, and sky glow, and should not negatively impact on protected views, designated heritage assets and their settings, or the amenity of nearby residents.

3.9.10 The list of impacts of tall buildings in Policy D9 Tall buildings is not exhaustive and other impacts may need to be taken into consideration. For example, the impact of new tall buildings in proximity to waterbodies supporting notable bird species upon the birds’ flight lines may need to be considered.

3.9.11 Safety considerations must be central to the design and operation of tall buildings. Policy D11 Safety, security and resilience to emergency provides information on how to ensure the design of buildings follows best practice to minimise the threats from fire, flood, terrorism, and other hazards and Policy D12 Fire safety sets out specific requirements to address fire risk.

Policy D10 Basement development

3.10.1 High residential land values and development constraints have led to increasing levels of basement development beneath existing buildings, particularly within central and inner London boroughs.

3.10.2 The construction of basements can cause significant disturbance and disruption if not managed effectively, especially where there are cumulative impacts from a concentration of subterranean developments. Large-scale basements (i.e. those that are multi-storey and/or those that extend significantly beyond the existing building footprint) can cause particular issues, especially when located in residential or higher density mixed-use areas. Such basement development can impact on land and structural stability as well as causing localised flooding or drainage issues. The extent and duration of construction of large-scale basements can also lead to a large number of HGV trips, as well as noise and vibration issues, causing disturbance to local residents. Measures such as requiring Construction Method and Management Plans can help protect neighbours during construction. Other consents and regulatory regimes may also be involved, such as Environmental Health in regard to noise and contamination, and Highways in relation to licences for skips and temporary structures.

3.10.3 The Mayor supports boroughs in restricting large-scale basement excavations under existing properties where this type of development is likely to cause unacceptable harm. Local authorities are advised to consider the following issues, including any cumulative impacts, alongside other relevant local circumstances when developing their own policies for basement developments: local ground conditions; flood risk and drainage impacts; land and structural stability; protection of trees, landscape, and biodiversity; archaeology and heritage assets; neighbour amenity; air and light pollution; and the impacts of noise, vibration, dust and site waste. Where particular and cumulative flood risk issues exist, boroughs should consider restricting the use of basements for non-habitable uses. The Agent of Change Principle (Policy D13 Agent of Change) should be applied to basement development to limit the impact of ground-borne noise and vibration from existing uses and infrastructure. Further guidance will be provided in Supplementary Planning Guidance.

3.10.4 Most proposals for the construction of a basement will require planning permission. These proposals need to be managed sensitively through the planning application process to ensure that their potential impact on the local environment and residential amenity is acceptable.

3.10.5 Basement development (small or large) can also cause significant noise and vibration disturbance through the reflection/focusing of ground-borne vibration originating from existing infrastructure, such as London Underground infrastructure, if this issue is not considered and managed effectively during its design and construction. Impact assessments prior to construction should consider the effects on the ground-borne vibration environment and propose appropriate mitigation, especially for surrounding residents.

3.10.6 The Mayor considers that smaller-scale basement excavations, where they are appropriately designed and constructed, can contribute to the efficient use of land, and provide extra living space without the costs of moving house. In areas where basement developments could cause particular harm, boroughs can consider introducing Article 4 Directions to require smaller-scale proposals to obtain planning permission.

Policy D11 Safety, security and resilience to emergency

3.11.1 Londoners look to the Mayor as a civic leader for support, advice and reassurance in the event of a major incident taking place. The role of the Mayor in an attack is an interconnected one and is clarified via his attendance at COBR[32] meetings about incidents affecting, or potentially affecting, London. The London Resilience Partnership maintains the London Risk Register[33]. The London Risk Register provides a summary of the main risks affecting London and identifies the existing risk management arrangements for the risks.

3.11.2 New developments, including building refurbishments, should be constructed with resilience at the heart of their design. In particular they should incorporate appropriate fire safety solutions and represent best practice in fire safety planning in both design and management. The London Fire Commissioner should be consulted early in the design process to ensure major developments have fire safety solutions built-in. Flooding issues and designing out the effects of flooding are addressed in Chapter 9.

3.11.3 Measures to design out crime, including counter terrorism measures, should be integral to development proposals and considered early in the design process, taking into account the principles contained in guidance such as the Secured by Design Scheme[34] published by the Police. Further guidance is provided by Government on security design[35]. This will ensure development proposals provide adequate protection, do not compromise good design, do not shift vulnerabilities elsewhere, and are cost-effective. Development proposals should incorporate measures that are proportionate to the threat of the risk of an attack and the likely consequences of one.

3.11.4 By drawing upon current Counter Terrorism principles, new development, including streetscapes and public spaces, should incorporate elements that deter terrorists, maximise the probability of their detection, and delay/disrupt their activity until an appropriate response can be deployed. Consideration should be given to physical, personnel and electronic security (including detailed questions of design and choice of materials, vehicular stand off and access, air intakes and telecommunications infrastructure). The Metropolitan Police (Designing Out Crime Officers and Counter Terrorism Security Advisors) should be consulted to ensure major developments contain appropriate design solutions, which mitigate the potential level of risk whilst ensuring the quality of places is maximised.

Policy D12 Fire safety

3.12.1 The fire safety of developments should be considered from the outset. Development agreements, development briefs and procurement processes should be explicit about incorporating and requiring the highest standards of fire safety. How a building will function in terms of fire, emergency evacuation, and the safety of all users should be considered at the earliest possible stage to ensure the most successful outcomes are achieved, creating developments that are safe and that Londoners can have confidence living in and using.

3.12.2 The matter of fire safety compliance is covered by Part B of the Building Regulations. However, to ensure that development proposals achieve the highest standards of fire safety, reducing risk to life, minimising the risk of fire spread, and providing suitable and convenient means of escape which all building users can have confidence in, applicants should consider issues of fire safety before building control application stage, taking into account the diversity of and likely behaviour of the population as a whole.

3.12.3 Applicants should demonstrate on a site plan that space has been identified for the appropriate positioning of fire appliances. These spaces should be kept clear of obstructions and conflicting uses which could result in the space not being available for its intended use in the future.

3.12.4 Applicants should also show on a site plan appropriate evacuation assembly points. These spaces should be positioned to ensure the safety of people using them in an evacuation situation.

3.12.5 Developments, their floor layouts and cores need to be planned around issues of fire safety and a robust strategy for evacuation from the outset, embedding and integrating a suitable strategy and relevant design features at the earliest possible stage, rather than features or products being applied to pre-determined developments which could result in less successful schemes which fail to achieve the highest standards of fire safety. This is of particular importance in blocks of flats, as building users and residents may be less familiar with evacuation procedures.

3.12.6 Suitable suppression systems (such as sprinklers) installed in buildings can reduce the risk to life and significantly reduce the degree of damage caused by fire, and should be explored at an early stage of building design.

3.12.7 The provision of stair cores which are suitably sized, provided in sufficient numbers and designed with appropriate features to allow simultaneous evacuation should also be explored at an early stage and provided wherever possible.

3.12.8 Policy D5 Inclusive design requires development to incorporate safe and dignified emergency evacuation for all building users, by as independent means as possible. In all developments where lifts are installed, Policy D5 Inclusive design requires as a minimum at least one lift per core (or more, subject to capacity assessments) to be a suitably sized fire evacuation lift suitable to be used to evacuate people who require level access from the building. Fire evacuation lifts and associated provisions should be appropriately designed and constructed, and should include the necessary controls suitable for the purposes intended.

3.12.9 Fire statements should be submitted with all major development proposals. These should be produced by a third-party independent, suitably-qualified assessor. This should be a qualified engineer with relevant experience in fire safety, such as a chartered engineer registered with the Engineering Council by the Institution of Fire Engineers, or suitably qualified and competent professional with the demonstrable experience to address the complexity of the design being proposed. This should be evidenced in the fire statement. Planning departments could work with and be assisted by suitably qualified and experienced officers within borough building control departments and/or the London Fire Brigade, in the evaluation of these statements.

3.12.10 Fire safety and security measures should be considered in conjunction with one another, in particular to avoid potential conflicts between security measures and means of escape or access of the fire and rescue service. Early consultation between the London Fire Brigade and the Metropolitan Police Service can successfully resolve any such issues.

3.12.11 Refurbishment that requires planning permission will be subject to London Plan policy. Some refurbishment may not require planning permission; nevertheless, the Mayor expects steps to be taken to ensure all existing buildings are safe, taking account of the considerations set out in this policy, as a matter of priority.

Policy D13 Agent of Change

3.13.1 For a long time, the responsibility for managing and mitigating the impact of noise and other nuisances on neighbouring residents and businesses has been placed on the business or activity making the noise or other nuisance, regardless of how long the business or activity has been operating in the area. In many cases, this has led to newly-arrived residents complaining about noise and other nuisances from existing businesses or activities, sometimes forcing the businesses or other activities to close.

3.13.2 The Agent of Change principle places the responsibility for mitigating the impact of noise and other nuisances firmly on the new development. This means that where new developments are proposed close to existing noise-generating uses, for example, applicants will need to design them in a more sensitive way to protect the new occupiers, such as residents, businesses, schools and religious institutions, from noise and other impacts. This could include paying for soundproofing for an existing use, such as a music venue. The Agent of Change principle works both ways. For example, if a new noise-generating use is proposed close to existing noise-sensitive uses, such as residential development or businesses, the onus is on the new use to ensure its building or activity is designed to protect existing users or residents from noise impacts.

3.13.3 The Agent of Change principle is included in the National Planning Policy Framework, and Planning Practice Guidance provides further information on how to mitigate the adverse impacts of noise and other impacts such as air and light pollution.[36]

3.13.4 The Agent of Change principle predominantly concerns the impacts of noise-generating uses and activities but other nuisances should be considered under this policy. Other nuisances include dust, odour, light and vibrations (see Policy SI 1 Improving air quality and Policy T7 Deliveries, servicing and construction). This is particularly important for development proposed for co-location with industrial uses and the intensification of industrial estates (see Part D4 of Policy E7 Industrial intensification, co-location and substitution). When considering co-location and intensification of industrial areas, boroughs should ensure that existing businesses and uses do not have unreasonable restrictions placed on them because of the new development.

3.13.5 Noise-generating cultural venues such as theatres, concert halls, pubs, night-clubs and other venues that host live or electronic music should be protected (see Policy HC5 Supporting London’s culture and creative industries). This requires a sensitive approach to managing change in the surrounding area. Adjacent development and land uses should be brought forward and designed in ways which ensure established cultural venues remain viable and can continue in their present form without the prospect of licensing restrictions or the threat of closure due to noise complaints from neighbours.

3.13.6 As well as cultural venues, the Agent of Change principle should be applied to all noise-generating uses and activities including schools, places of worship, sporting venues, offices, shops, industrial sites, waste sites, safeguarded wharves, rail and other transport infrastructure.

3.13.7 Housing and other noise-sensitive development proposed near to an existing noise-generating use should include necessary acoustic design measures, for example, site layout, building orientation, uses and materials. This will ensure new development has effective measures in place to mitigate and minimise potential noise impacts or neighbour amenity issues. Mitigation measures should be explored at an early stage in the design process, with necessary and appropriate provisions secured through planning obligations.

3.13.8 Ongoing and longer-term management of mitigation measures should be considered, for example through a noise management plan. Policy T7 Deliveries, servicing and construction provides guidance on managing the impacts of freight, servicing and deliveries.

3.13.9 Some permitted development, including change of use from office to residential, requires noise impacts to be taken into consideration by the Local Planning Authority as part of the prior approval process. Boroughs must take account of national planning policy and guidance on noise, and therefore the Agent of Change principle would apply to these applications.

3.13.10 Noise and other impact assessments accompanying planning applications should be carefully tailored to local circumstances and be fit for purpose. That way, the particular characteristics of existing uses can be properly captured and assessed. For example, some businesses and activities can have peaks of noise at different times of the day and night and on different days of the week, and boroughs should require a noise impact assessment to take this into consideration. Boroughs should pay close attention to the assumptions made and methods used in impact assessments to ensure a full and accurate assessment.

3.13.11 Reference should be made to Policy D14 Noise which considers the impacts of noise-generating activities on a wider scale and Policy SI 1 Improving air quality which considers the impacts of existing air pollution. Further guidance on managing and mitigating noise in development is also provided in the Mayor’s London Environment Strategy.

Policy D14 Noise

3.14.1 The management of noise is about encouraging the right acoustic environment, both internal and external, in the right place at the right time. This is important to promote good health and a good quality of life within the wider context of achieving sustainable development. The management of noise should be an integral part of development proposals and considered as early as possible. Managing noise includes improving and enhancing the acoustic environment and promoting appropriate soundscapes. This can mean allowing some places or certain times to become noisier within reason, whilst others become quieter. Consideration of existing noise sensitivity within an area is important to minimise potential conflicts of uses or activities, for example in relation to internationally important nature conservation sites which contain noise-sensitive wildlife species, or parks and green spaces affected by traffic noise and pollution. Boroughs, developers, businesses and other stakeholders should work collaboratively to identify the existing noise climate and other noise issues to ensure effective management and mitigation measures are achieved in new development proposals.

3.14.2 The Agent of Change Principle places the responsibility for mitigating impacts from existing noise-generating activities or uses on the new development. Through the application of this principle existing land uses should not be unduly affected by the introduction of new noise-sensitive uses. Regard should be given to noise-generating uses to avoid prejudicing their potential for intensification or expansion.

3.14.3 The management of noise also includes promoting good acoustic design of the inside of buildings. Section 5 of BS 8223:2014 provides guidance on how best to achieve this. The Institute of Acoustics has produced advice, Pro:PG Planning and Noise (May 2017), that may assist with the implementation of residential developments. BS4214 provides guidance on monitoring noise issues in mixed residential/industrial areas.

3.14.4 Deliberately introducing sounds can help mitigate the adverse impact of existing sources of noise, enhance the enjoyment of the public realm, and help protect the relative tranquillity and quietness of places where such features are valued. For example, playing low-level music outside the entrance to nightclubs has been found to reduce noise from queueing patrons, leading to an overall reduction in noise levels. Water features can be used to reduce the traffic noise, replacing it with the sound of falling water, generally found to be more pleasant by most people.[37]

3.14.5 Heathrow and London City Airport Operators have responsibility for noise action plans for airports. Policy T8 Aviation sets out the Mayor’s approach to aviation-related development.

3.14.6 The definition of Tranquil Areas, Quiet Areas and spaces of relative tranquillity are matters for London boroughs. These are likely to reflect the specific context of individual boroughs, such that Quiet Areas in central London boroughs may reasonably be expected not to be as quiet as Quiet Areas in more residential boroughs. Defra has identified parts of Metropolitan Open Land and local green spaces as potential Quiet Areas that boroughs may wish to designate.[38]

[26] PTAL and Time Mapping (TIM) catchment analysis is available on TfL’s WebCAT webpage. TIM provides data showing access to employment, town centres, health services, and educational establishments as well as displaying the population catchment for a given point in London (see PTAL in glossary for more information on WebCAT and Time Mapping).

[27] Design Review Principles and Practice, The Design Council, et al, 2013, available at: https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/sites/default/files/asset/document/DC%20Cabe%20Design%20Review%2013_W_0.pdf

[28] Higher density residential developments are those with a density of at least 350 units per hectare

[29] Shaping London: How can London deliver good growth?, Mayor's Design Advisory Group, 2016

[30] This is governed by the Building Regulations 2010: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2010/2214/pdfs/uksi_20102214_en.pdf and the Building Regulations &c. (Amendment) Regulations 2015: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2015/767/pdfs/uksi_20150767_en.pdf

[31] https://www.gov.uk/guidance/housing-optional-technical-standards

[32] COBR (often referred to as COBRA) stands for Cabinet Office Briefing Rooms, these are the locations the Government’s emergency response committee set up to respond to major events and emergencies.

[33] For further details see http://www.london.gov.uk/mayor-assembly/mayor/london-resilience

[34] For further details see http://www.securedbydesign.com/

[35] Crowded Places Guidance, National Counter Terrorism Security Office, 2017: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/crowded-places-guidance; Crowded Places: The Planning System and Counter-Terrorism, Home Office and DCLG, 2012; and Protecting crowded places: design and technical issues, Home Office, Centre for the Protection of National Infrastructure and the National Counter-Terrorism Security Office, 2014: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/crowded-places

[36] National Planning Policy Guidance, Ministy of Housing, Communities & Local Government, 2014, https://www.gov.uk/guidance/noise--2

[37] For more information on approaches to minimise noise related to road and rail traffic, aircraft, water transport and industry see the Mayor’s Environment Strategy

[38] Noise Action Plan: Agglomerations Environmental Noise (England) Regulations 2006 (as amended), Department for Environment Food & Rural Affairs, 2014: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/276228/noise-action-plan-agglomerations-201401.pdf

Notes and Errata