Key information

Publication type: London Plan Guidance

Publication status: Draft

Contents

5 sections

1. Introduction

1.1 Purpose

The purpose of this London Plan Guidance is to help interpret and implement the Intend to Publish London Plan (London Plan) policies on housing design, optimising site capacity on all scales of site and enabling housing supply through smaller housing developments, with the wider purpose of supporting Good Growth. The document sets out a design-led approach to intensification, using residential types to quickly identify the indicative capacity of a site or area, with careful consideration of housing design standards that protect quality of life for residents.

The document provides guidance on assessing the capacity of land and buildings to accommodate housing by optimising site capacity at all stages of the planning process (plan-making, site allocation, area-based strategies, pre- application discussions and application determination). The National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF, 2019) encourages the use of ways of proactively granting permission for new housing. This document provides guidance to boroughs and neighbourhood forums for bringing forward high-quality homes by way of development orders and Permission in Principle (PiP).

The Government and the Mayor recognise that small housing development should play a greater role in the provision of additional homes. This guidance provides advice on how opportunities to deliver new homes on small housing developments should be identified, shaped and permitted to meet London’s housing needs and deliver contextually appropriate, better quality design (London Plan Policy H2: Small sites).

Housing is the most common land use in London, yet there is not enough. Its inclusion as part of mixed-use developments in town centres, high streets, and some industrial areas, can enliven places and make them more attractive and safer, as well as providing much needed additional homes. This guidance provides advice on how housing can be successfully integrated with a range of uses and building types to provide successful places and high-quality additional homes. The guidance focuses on general needs housing across tenures, including Build to Rent. However, it does not provide advice on specialist forms of housing such as housing for students or older people. Relevant London Plan policies and other guidance are referenced throughout the document.

1.2 Structure

This London Plan Guidance is constructed as a series of modules.

Foreword: Good Quality Homes For All Londoners

The foreword communicates the Mayor’s vision for high-quality housing, particularly housing delivering improved quality of life through design-led processes of site optimisation. This narrative situates the purpose and content of the Housing Design London Plan Guidance within the wider context of the Greater London Authority’s mission to ensure Good Growth and provide good quality housing for all Londoners.

Module A: Optimising Site Capacity - A Design-led Approach

Module A advocates a design led methodology for optimising site capacity at the plan making stage. It is aimed at borough policy officers when calculating capacity on strategic and non-strategic site allocations. It sets out an approach to assessing sites’ suitability for development and offers a tool for assessing site capacity.

The module provides a range of residential types to test site capacity. The most common existing and emerging housing types are categorised based on their typical characteristics, access and circulation arrangements and their ability to meet Module C’s housing design quality standards. Each type is described in terms of its inherent qualities, characteristics, flexibility to accommodate different tenure and type mixes and suitability for integration with mixed uses. Module A provides guidance on the residential type suitable for a s site, in order to determine potential capacity.

Module B: Small Housing Developments - Assessing Quality and Preparing Design Codes

Providing guidance on both assessing the quality of small sites schemes and preparing design codes, Module B will help boroughs to optimise development opportunities on sites below 0.25 of a hectare and deliver on their small sites housing targets set out in London Plan Policy H2 (Small sites). To do this, the module explores the typical conditions found across London which might be suitable for small site development and offers examples of how a borough could write design codes linked to the Housing Design – Quality and Standards identified in Module C, offering template design codes Case studies of successful small sites development are included in Module D and can be referenced when writing codes as best practice examples.

Module C: Housing Design - Quality and Standards

Module C updates the London Housing Design Guide (2010). It is aimed at borough development management officers and developers and their design teams seeking planning permission. The guidance is categorised under the broad themes of Shaping Good Places, Designing for a Diverse City, From Street to Front Door, Dwelling Space Standards, Home as a Place of Retreat, Living Sustainably and Future Proofing. In addition to providing technical standards where applicable, Module C provides qualitative guidance, with reference to best practice examples (in Module D: Housing Design- Case Studies and Appendices), to demonstrate where good design has been critical to a positive resident experience.

Module D: Housing Design - Case Studies and Appendices

Module D is a library of best practice case studies, additional information on the planning process and a glossary of terms used within the London Plan Guidance.

1.3 Who is it for?

The document comprises four modules that seek to provide helpful guidance and increased certainty for all Londoners that good growth is possible and will happen. This guidance is aimed at landowners, prospective developers, architects and wider design teams, planners and decision-makers across the public, private and community sectors. The different modules will be of different levels of interest to different parties. The guidance also hopes to provide local communities with confidence that the Mayor is determined to work with development partners to deliver growth that safeguards amenity and helps ensure that all Londoners have a good quality of life.

Module B is principally aimed at borough policy officers tasked with writing local policy.

1.4 Introduction to Module B

Good growth across London requires high quality residential development at all scales of delivery. Londoners living in existing communities deserve to experience the benefits of growth and change irrespective of its scale. Community support for intensification of existing neighbourhoods through conversion, extension, additional development on underused land, and demolition and redevelopment on brownfield land, will only be achieved at scale if boroughs enable character-specific, good quality design and construction. Where borough planning policy and design guidance is clear and up to date, development on small sites can realise the incremental growth needed within existing neighbourhoods, whilst offering developers and communities increased sight of and certainty about planning outcomesReference:1.

This module directly contributes to the wider good growth by design programme by setting standards and articulating best practice for the delivery of smaller developments. It seeks to ensure such developments support the creation of successful, inclusive and sustainable places by providing a flexible, template design code that boroughs can immediately apply to small housing development sitesReference:2.

This module also provides guidance to enable boroughs to prepare their own design codes to reflect the specific characteristics or opportunities for smaller housing developments in their area. This includes advice on how to prioritise the production of design codes for smaller housing developments and how to define aspects of design codes in relation to street-facing and backland conditions. To explain how the housing design standards (Housing Design- Quality and Standards Module C) may be applied within these design codes, the document concludes with two illustrative design codes for an upward extension and a street-facing infill development. These examples can then be adapted by the boroughs to suit the local context.

Further guidance on residential types suitable for smaller housing development, housing design standards and case studies demonstrating how existing residential design in London has enhanced local character and improved quality of life can be found in Module A (Section 3.2, Types A-C), Module C and D respectively.

2. Design Coding for Small Housing Developments for Incremental Growth

2.1 Design codes

Design code: describes the key design principles of a development proposal in a simple, concise and mainly graphic format. By drawing on the proposal’s approach to layout, massing and height, the code defines the principal features that make up the overall design integrity of the scheme.

Good growth is best served by setting clear design requirements that aren’t overly prescriptive or unnecessarily frustrating for development, and that take account of affordability and wellbeing. This is especially important when delivering new homes within existing neighbourhoods.

To create certainty and stimulate high quality, residential development, design codes should be proportionate, context specific and support the realisation of London-wide and borough-wide planning policy and design governance. Undertaking effective design coding that interprets the character of existing neighbourhoods and establishes place-specific design principles requires time, design capacity and expertise.

The fundamental approach and principles presented in this guide may be used as a basis for the development of more context-specific design codes by boroughs. Boroughs should develop design codes in line with the Housing Design Quality and Standards (Module C). These aim to avoid matters of style to encourage the level of architectural innovation and diversity required to tackle complex issues such as dealing with small sites. However, if the design code is being written for a conservation area or an area that has a valued prevalent architectural character, boroughs may wish to address sensitive local issues when developing their code under design quality and standards category

C1.1 ‘Response to character and context’. These could incorporate issues such as boundary treatments, architectural treatment and materiality into adapted design codes to support a contextual approach to development. Characterisation and contextual analysis undertaken as part of borough-wide area-assessments provides an understanding of the character of existing neighbourhoods and their capacity for growth (Module A, Section 1.4).

Boroughs should use judgement about the level of prescription contained within codes to ensure design principles direct a context-based response, without limiting the innovation necessary to successfully realise good design and optimise housing delivery within constrained sites. Where appropriate, design codes may be combined with Local Development Orders (LDOs) to enable positive growth and incentivise appropriate investment through added certainty. The potential of design codes to stimulate development and deliver good design is most likely to be realised when implemented as part of a borough-led approach to design governance and scrutiny across scales (London Plan Policy D4). Where available, boroughs should engage relevant design experts at the borough-level during the preparation of design codes. Boroughs should undertake meaningful community engagement, in accordance with up to date Statements of Community Involvement, to support the development of design codes that reflect the concerns and aspirations of Londoners living in existing neighbourhoods likely to be affected by and benefit from change.

2.2 Small housing developments

Small housing developments: residential developments on sites up to 0.25 hectares. This may include new build; infill development on vacant or under- used sites; upward extensions of existing buildings (including non-residential developments); residential conversions, redevelopment and extension of existing sites.

Small housing developments offer an opportunity to increase optimum residential density of an area while providing Londoners with homes that are respectful of local character. Boroughs are responsible for promoting good design, and proactively increasing housing provision, through small housing developments. These can be delivered through the use of plan-making and decision-making informed by area-wide design coding, masterplans and site- specific design briefs (London Plan Policy H2 B).

2.3 Forms of small housing development

Residential types appropriate for the development of small housing developments are outlined in Module A (Section 3.2, Types A-C). Small housing development may occur on small sites of below 0.25 hectares and will contribute to borough-wide small site net housing completion targets (H2: Table 4.2).

2.4 Design code prioritisation

Boroughs will likely have to produce several design codes to address multiple and differing character areas. It is therefore important to prioritise coding for areas most likely to benefit from small development sites. Incremental intensification of existing residential areas with higher connectivity - afforded by proximity to transport infrastructure or town centres - is expected to play an important role in the delivery of small site development. As such, boroughs are advised to consider town and edge of centre classifications, higher PTAL areas (3-6 in particular), and future potential for growth through small housing developments when prioritising design coding.

Creating design codes in a timely way provides boroughs with an opportunity to drive the supply of well-designed, additional homes of diverse types and tenures on smaller sites. This process can also contribute to economic development by supporting small and medium-sized housebuilders and encouraging forms of community-led housing. Failure to prepare a design code in a timely way could result in small housing developments not realising their potential or being of poor design quality (London Plan Policy H2 B).

Once adopted, design codes should be reviewed as part of the development plan monitoring and evaluation process, and revised as required to reflect implementation and any changing circumstances.

2.5 Design codes responding to character and context

London does not have a homogenous character. Instead, it has a diverse range of characters, each with unique challenges and opportunities for good growth. Understanding the quality and character of the neighbourhood in which small housing development will be located is key to judging what constitutes an appropriate form and layout for the development, and also how best to secure a positive experience for existing and new residents. Small housing development is most likely to be successful where it responds to, and complements, the existing character of an area. In this way it can support the conservation or evolution of the area as identified by the local authority.

Small housing development will most commonly occur within existing neighbourhoods where characterisation and area assessment has identified a capacity for limited or moderate growth (Module A, Section 1.6). As small housing development occurs on smaller, constrained sites near to existing dwellings, it is critical that it is the product of careful design. It is important to balance growth with the protection of existing amenity. When optimised in this way, small housing development can add value to existing neighbourhoods and deliver good growth.

Small housing development will succeed where it complements and responds innovatively to the predominant character of the neighbourhood. Importantly, complementing means that the new development should draw from, and contribute to, the evolution of the existing context (where evolution has been identified as appropriate). It may not be necessary to closely replicate existing forms of development. Innovation may be necessary to realise well-designed small housing development and quality of life. This will require reinterpretation, rather than simple imitation.

London provides a rich source of established planning practice in relation to managing change and incremental intensification through small housing development. A close reading of built form, massing, material choice, detailing and style within the neighbourhood will inspire an innovative proposal that seeks to complement, or potentially contrast, with existing buildings. Where this is executed well, small housing developments may come to express the best of change by offering residents, both new and existing, a positive quality of life.

Boroughs should prepare design codes and broader forms of design governance that clarify the character of a place and the elements that are important for new development to respect. This encourages reinterpretation of place to promote innovation, and maximises the capacity of new development to successfully integrate with existing neighbourhoods.

Relevant case studies:

D3.2 Sheendale

D3.3 Caudale

3. Identifying Opportunities for Small Housing Development

3.1 Small housing development conditions

Encouraging well-designed small housing developments is best understood though an exploration of the opportunities that arise for development in street- facing sites and backland sites. These are most frequently associated with terraces (Illustration B.1) and semi-detached houses (Illustration B.2). Street-facing conditions and backland conditions produce differing design challenges and opportunities. In turn, these create different requirements for design codes. A range of small housing developments can occur in both street-facing (Section 3.3) and backland conditions (Section 3.4).

Types of small housing developments:

- Street-facing conditions: site with direct access to the street.

- Backland conditions: site behind development, commonly underused rear land and in some cases brownfield land.

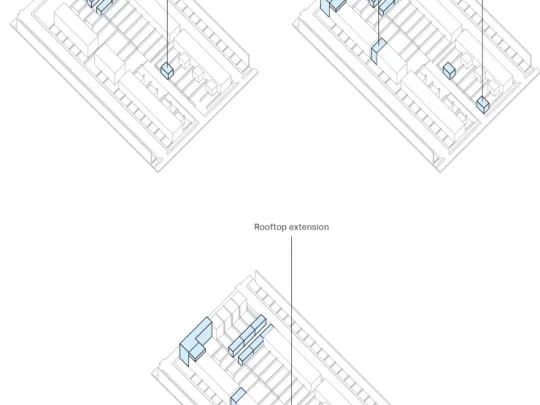

Figure 3.1: Illustration B.1 Opportunities for small housing development within terraced context

Figure 3.2: Illustration B.2 Opportunities for small housing development within semi-detached contexts

3.2 Assessing the potential for small housing developments

Following area assessment, characterisation and assessment of land supply, it is recommended that boroughs undertake an initial assessment of the character of existing neighbourhoods for their potential to accommodate different forms of small housing development (in accordance with Module A). Street-facing conditions and backland conditions provide broad categories for initial searches. Categories of infill development within the curtilage of a house, residential conversions, demolition, and redevelopment or extension of existing buildings, provide useful subcategories.

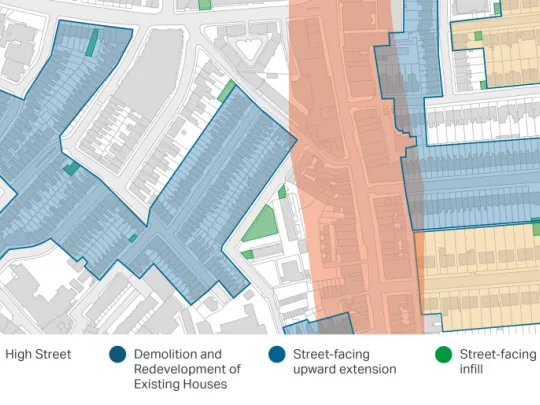

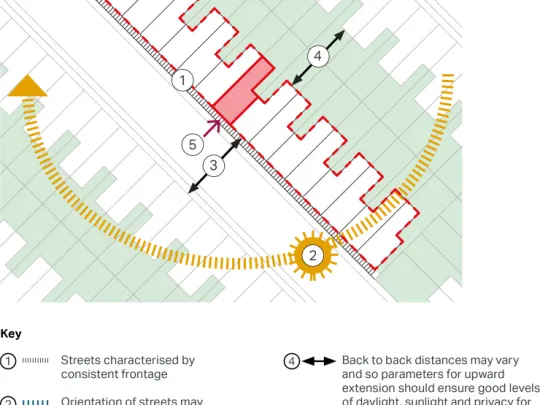

Illustration B.3 shows a high street (shaded red) of a town centre. The other shaded areas have been identified as being able to accommodate three potential forms of small housing development: street-facing upward extension (blue), street- facing infill (green), and demolition and redevelopment (yellow). A design code could be produced for each of these types (Module B, Section 2.4).

Where small housing development occurs in street-facing conditions, design codes should emphasise guidance in relation to frontage line, front-to-front distances, building heights and rear building line projects (Section 3.3.1-3.3.4). For backland conditions, design codes should focus on guidance related to light and privacy, building heights and roof form (Section 3.4.1-3.4.3).

Figure 3.3: Illustration B.3 Potential for the integration of different forms of small housing development

3.3 Street-facing conditions

On a street-facing plot, the character of the existing street scene will closely inform the relationship between the proposed development and the existing surrounding buildings. This character will guide formal considerations such as frontage line, front-to-front distances, building heights, rear projections and roof forms.

The same considerations will apply to a variety of street-facing site types, including:

-

Conversion of houses into flats

-

Additions to the front or side of an existing property or within the curtilage of one

-

Demolition and redevelopment of existing homes

-

Redevelopment of flats and non-residential buildings with a street-facing condition.

Frontage line

Consideration should be given to the frontage lines of any new development that faces the street. Infill development should generally be consistent with the existing frontage line of the street within which it is located.

Typically, terraced housing has a regular, unbroken frontage line and any development should align with this unless it can be demonstrated that a different approach would not negatively impact the character of the street.

Streets of semi-detached and detached houses may have more variation in their frontage line, allowing flexibility in the positioning of new development in relation to the street. However, the frontage line of new development should not negatively impact the street scene or harm either the privacy or the daylight and sunlight enjoyed by occupiers of existing nearby dwellings. Nor should it create or exacerbate street canyons in areas of existing poor air quality. Small developments that bookend a street, or are located on a corner site, may have the opportunity to accommodate additional depth due to their potential for dual-aspect and prominent townscape position. In these locations, a frontage line that steps out in relation to adjacent buildings could be considered appropriate. Development on plots located at the junction between two different frontage lines should justify their alignment with either frontage line.

In town centre and high street contexts with mixed-use ground floors, building frontage lines often have a direct relationship with the pavement and do not include defensible space (i.e. an area clearly owned and maintained by an identifiable household). Consideration should be given to upper level balconies, which may need to be inset in order to avoid overhanging the pavement.

Consideration should also be given to describing measures to produce defensible space. This may be achieved through boundary treatment and physical distance, but may be produced by other means, e.g. material change at pavement level to signify division between public and semi-public space.

Relevant case studies:

D2.3 Adolphus Road

D3.5 Barretts Grove

Figure 3.4: Illustration B4

Front-to-front distances

Where small development infills a plot within an existing street, front-to-front distances will be governed by the character of the existing street and associated frontage lines. Where small housing developments can create a new streetscape, the street width (i.e. the separation distance between two facing building elevations) should generally be no less than the height of the facing buildings. This distance could be reduced if further testing of proposals and innovative design responses (e.g. articulated rooflines) can demonstrate that good levels of daylight, sunlight and privacy can be achieved.

Where existing building heights are greater than the width of the street, particular attention should be paid to designing new development to ensure that appropriate levels of daylight and sunlight can be achieved, and retained, for both new and existing homes respectively. Where testing demonstrates that neighbouring buildings’ heights to the front and rear produce overshadowing, distances between buildings may have to be increased.

Relevant case studies:

D4.2 Dujardin Mews

Figure 3.5: Illustration B.5 Frontage distances, terraced

Building height

The height of street-facing, small housing developments should purposefully address existing building height. For example, a key characteristic of terraced streets is their consistent eaves and roofline. This consistency presents opportunities to promote continuity by requiring mid-terrace developments to predominantly be equal in height with adjacent properties. However, it may also be appropriate to signal positive change by enabling end of terrace locations to accommodate a full additional storey in relation to the adjacent terrace.

Where appropriate, design codes may enable incremental intensification in response to known demand by describing principles for relative increases in height. In this way, a new, consistent eave height and roofline may be established. In all circumstances, it is critical to ensure that with increasing height all existing and surrounding properties will continue to receive good levels of daylight and sunlight.

In semi-detached contexts, new development should seek to accommodate a full additional storey. This should be partially contained within the roof space if possible to ensure that the characteristic scale of the buildings along the street is maintained.

In town centres, proposals with building heights that exceed their surroundings should demonstrate how the additional height does not negatively impact on the street character and the collective urban arrangement. The height of new development should not unreasonably impact on the daylight and sunlight enjoyed by existing residential properties. Nor should it increase the depth of existing street canyons, or create new street canyons, where existing poor air quality might be exacerbated by the canyon effect.

Relevant case studies:

D3.4 Two Family Houses

Figure 3.6: Illustration B.6 Building heights, semi-detached

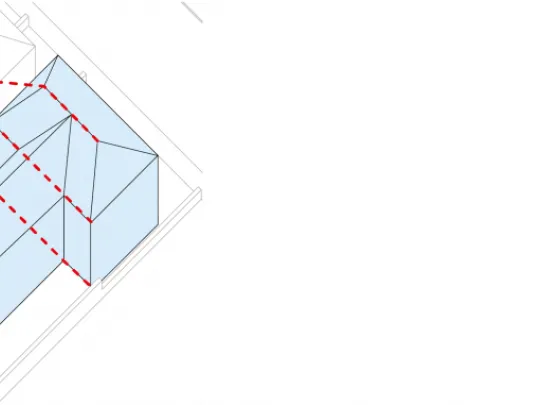

Rear building line projection

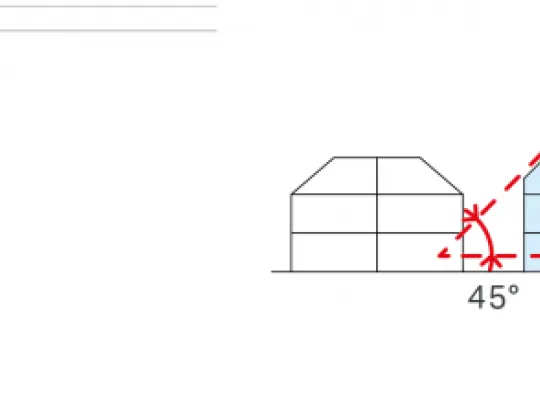

Where a development projects beyond a rear building line, it should be demonstrated that there would be no unreasonable impact on the amenity of neighbouring homes in relation to daylight, sunlight and privacy.

A good rule of thumb would be to follow the 45-degree rule illustrated below. In this, the height and the depth of the projection should not breach a 45-degree line drawn from the centre of the window of the lowest, and closest, habitable room on the neighbouring property.

Figure 3.7: Illustration B.7 Rear building line projection, semi-detached (depth)

Rear projections should be carefully considered as part of the overall massing of the proposal and avoid complex stepping within the 45-degree lines. The flank elevations of any projections should be carefully designed to ensure the privacy of neighbouring homes is maintained.

Figure 3.8: Illustration B.8 Rear building line projection, semi-detached

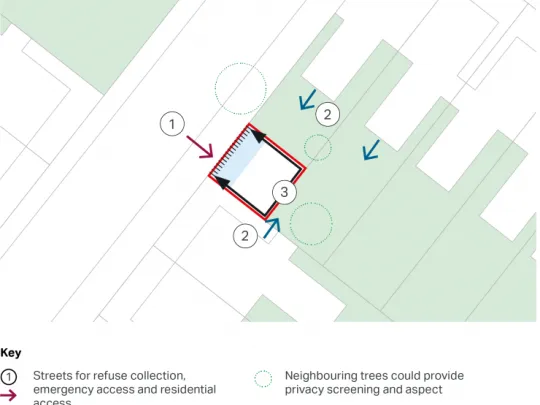

3.4 Backland conditions

Whereas developments in street-facing conditions are generally governed by a clearer set of rules established by the urban order of an existing streetscape, backland sites require more innovation and reinterpretation to enable development. Consideration of access and servicing and the inter-relationship between overlooking, privacy, aspect and daylight, and sunlight are paramount to the success and acceptability of new development in backland locations.

The same considerations will apply to a variety of backland site types, including:

-

Backland infill development on vacant or underused sites

-

Redevelopment of garage sites

-

Infill development within the curtilage of a house.

Figure 3.9: Illustration B.9 Backland conditions, relationship with existing buildings (terraced)

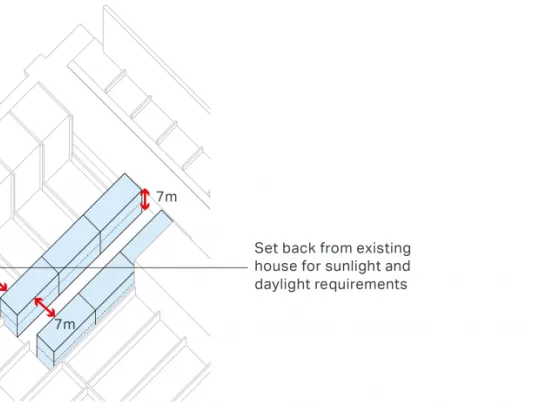

Daylight, sunlight and privacy

Where proposed development is in close proximity to the rear elevations of neighbouring existing homes and typical separation distances cannot be achieved, there are two key considerations that will shape the scale and massing of the proposal:

-

Adequate daylight and sunlight should be ensured for future residents as well as no unacceptable loss of daylight or sunlight for neighbours

-

Adequate privacy should be maintained for both future and existing residents.

The two considerations are clearly related - windows allow daylight and sunlight into the home and yet they also allow aspect into and out of the home. The design response should carefully balance both considerations to reach a successful solution.

Proposed homes in close proximity to existing homes will need to allow adequate daylight and sunlight to reach the façades of neighbouring homes. In addition, proposals that are close to existing homes should ensure adequate privacy for all residents by avoiding windows serving habitable rooms that directly face windows that serve habitable rooms in neighbouring homes.

This could be achieved through a combination of design techniques such as:

-

Orientating new homes so they are directed away from existing neighbouring homes

-

Using courtyards to provide aspect to outdoor spaces and to bring in daylight (care should be taken to ensure that emission sources, such as boilers, are positioned to avoid accumulation of air pollution in courtyards)

-

Using rooflights to bring light into the home

- Screening windows and amenity spaces to avoid direct overlooking.

Relevant case studies

D2.3 Adolphus Road

D4.1 Foundry Mews

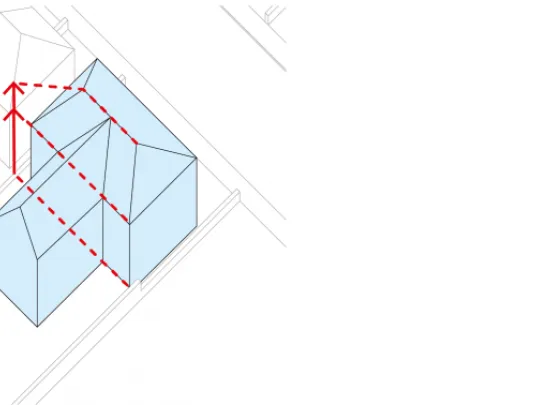

Building height

Consideration should be given to the height of backland development to ensure a sense of openness is maintained on small plots, and also to avoid unreasonable impact on the daylight and sunlight enjoyed by existing homes.

If a site is within close proximity to rear residential building lines, clever use of roof space and form can help to accommodate additional floor space or taller floor-to-ceiling heights, whilst still being sensitive and respectful to neighbouring properties.

Where backland sites are big enough to accommodate development of a larger scale and where separation distances allow, height should be in line with the predominant surrounding building height. Where additional height is proposed, proposals should demonstrate how the massing of the building has been developed to ensure long views are maintained. This could be through stepping rooflines, allowing light and views between buildings.

Relevant case studies

D3.1 Otts Yard

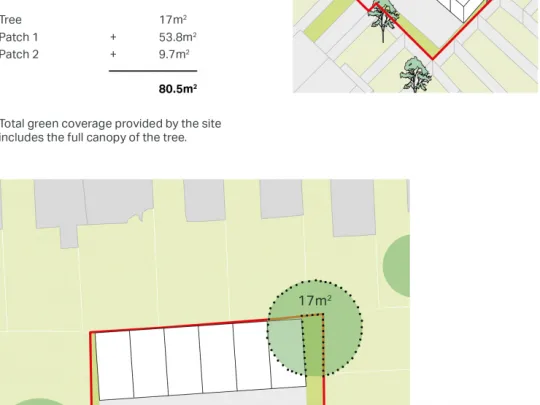

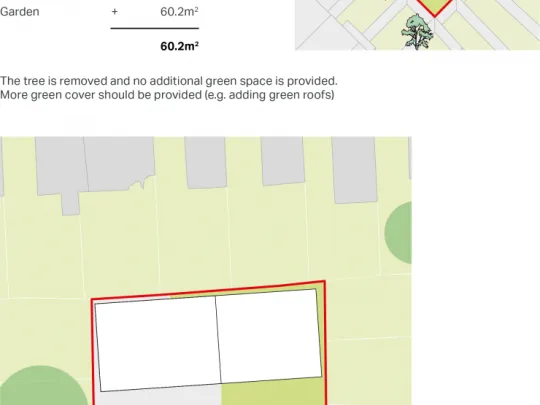

Green cover

In considering the development of backland sites regard should be had to urban greening. For major developments (10 units and above) the Urban Greening Factor will apply and for smaller housing developments there should be no net loss of green cover as set out in Module C. There are multiple ways to achieve this, for example providing green amenity space, planting trees, incorporating green roofs and including other greening measures such as sustainable drainage systems. Priority should be given to retaining or providing green features that have multiple green infrastructure benefits. Examples of how to achieve this are presented in the diagrams overleaf.

In developing design codes boroughs should consider how local evidence and green infrastructure strategies inform greening opportunities and specific mitigation measures for different areas.

Roof form

Innovative use of roof space and form will be key to the success of small backland developments. Adopting a lower roof height and profile can help make new buildings subservient to their neighbours, reduce overshadowing, and maintain privacy. Roofs also provide opportunities to bring light into the home (e.g. through roof lights). Green roofs can provide valuable green infrastructure and increase biodiversity, ensuring no net loss of overall green cover when taking advantage of opportunities for backland development. Examples of how to achieve this are presented by the diagrams overleaf. Roofs can also be used for the installation of renewable technologies such as solar PV panels.

Relevant case studies

D1.2 Garden House

Worked example of backland conditions

Existing site

Figure 3.10: Illustration B.10

Proposal A

Figure 3.11: Illustration B.11

Proposal B

Figure 3.12: Illustration B.12

Proposal C

Figure 3.13: Illustration B.13

4. Example Design Codes for Small Housing Development

This section presents design codes to be used for small housing developments: street-facing upward extension (Section 4.1) and street-facing infill within curtilage (Section 4.2). Each design code is preceded by example analysis describing the characteristics of a selected scenario and an illustrated demonstration of how key design principles within the scenario may be applied. This preceding information provides a professional context for decision-making. Design codes for each small housing development context correspond to performance against quality measures within the Housing Design-Quality and Standards (Module C).

This information may also provide a useful basis for the development of area- specific design codes. The level of detail and degree of prescription contained within a code should be proportionate and tailored to the circumstances of each place. It should also allow a suitable degree of variety where this would be justified. An area-wide design code should cover analysis of opportunities and constraints, the resulting design principles, and the key parameters for development in relation to the Housing Design-Quality and Standards (Module C). Not all sections of Module C will be relevant to the form of development and location covered by a particular design code.

As a minimum, developments should adhere to all relevant London Plan policies including minimum space standards.

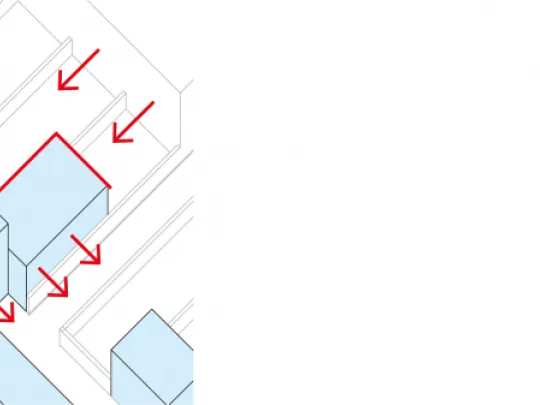

4.1 Street-facing upward extension

Site type description and analysis

Upward extension of existing terraced housing to release new homes.

Figure 4.1: Illustration B.14

Figure 4.2: Illustration B.15 Example site photograph

Figure 4.3: Illustration B.16 Potential opportunities across wider area

Key Principles

Figure 4.4: Illustration B.17

Design code performance against housing design standards

Below are the relevant housing standards from Module C which need to be met in order to accord with this design code.

C1 Shaping Good Places

C1.1 Response to character and context

-

Frontage line should be consistent with existing terrace.

-

One storey is allowed if this results in an increased number of dwellings. Additional storeys, e.g. at the end of terraces, to increase the number of dwellings will be permitted where additional height does not negatively impact on the character of the street.

-

Roof form, eaves and ridge heights should aim to achieve consistency with the terrace, so that a uniform height is reestablished over time as more properties in the terrace are extended.

-

Materiality, detailing and fenestration should reference the surrounding scale and character of neighbouring development.

C3 From Street to Front Door

C3.1 Access and servicing

-

Refuse access from street, front garden and/or yard should be shared between both dwellings to provide adequate space for waste storage.

-

Residential access from the street and emergency access from the street should be preserved.

C3.2 Safety and security

- Dwellings can share the entrance hallway but must have separate secure entrance doors.

C3.3 Cycle parking

- As a minimum, cycle parking must be provided in accordance with the London Plan Policy T5 and guidance contained in the London Cycling Design Standards.

C3.4 Car parking

- Parking should be provided at or below the maximum standards set out in London Plan Policy T6.1, including provision of disabled persons parking where applicable.

C4 Dwelling Space Standards

C4.1 Private internal space

- Must meet London Plan space standards.

C4.2 Private outside space

-

Must meet minimum London Plan standards.

-

There should be no projecting balconies over existing frontage lines.

-

New external amenity space should be well integrated and avoid reductions in privacy for neighbouring buildings, i.e. external amenity space for upper extensions should be in the form of a set-back terrace on the top floor to minimise overlooking and overshadowing of downstairs amenity space.

C4.3 Spatial quality

- Proposal should demonstrate high quality internal spaces that achieve good levels of daylight and sunlight, aspect and privacy.

C5 Home as a Place of Retreat

C5.1 Privacy

-

Existing street widths, back-to-back distances and window sizes should set acceptable levels of privacy. The upward extension should not negatively impact on the privacy or overlooking of neighbouring properties.

-

The upward extension should not negatively impact on the privacy or overlooking of neighbouring properties.

C5.2 Aspect and outlook

- Aspect to be street-facing or rear-garden facing.

C5.3 Daylight, sunlight and overshadowing

-

Consider the use of roof lights on the top floor.

-

Upward extensions must not result in unacceptable impacts to daylight and sunlight for surrounding properties.

-

Use existing street widths as a baseline to inform acceptable heights.

C6 Living Sustainably

C6.1 Environmental sustainability

-

Use sustainable materials.

-

Ensure high levels of fabric efficiency and energy efficient fixtures and fittings to reduce energy demand.

-

Supply energy efficiently and cleanly and maximise opportunity for renewable energy, where possible.

-

Overheating risk should be designed out and the need for active cooling avoided.

C6.2 Biodiversity and urban greening

- Green roofs should be incorporated where roof form and character and context allow.

C6.4 Air pollutant emissions

- Car-free developments are assumed to meet the transport emissions benchmark.

- Developments must meet the Air Quality Neutral benchmarks. On smaller housing developments, the building benchmarks can be met by using ultra- low NOx boilers or other less polluting technologies. These could include heat pumps, connection to an existing district heating scheme, fuel cells or renewables (excluding biomass).

C7 Future Proofing

C7.1 Flexibility and adaptability

- Dwelling layouts should demonstrate rooms are capable of flexible use and future adaptation.

C7.2 Safeguarding development potential

- Upward extension should only have windows facing the street or rear gardens, to safeguard the development potential of adjacent houses.

- Flank walls should be built to enable the upward extension of adjacent houses.

C7.3 Quality, maintenance and management

- Upward extensions should be constructed from materials that are robust, high quality, and reference the local context.

4.2 Street-facing infill within underused in-curtilage site

Site type description and analysis

Development of a garage plot or other backland with a street facing elevation, at the junction of two terraced streets.

Figure 4.5: Illustration B.18

Figure 4.6: Illustration B.19 Example site photograph

Figure 4.7: Illustration B.20 Potential opportunities

Key Principles

Figure 4.8: Illustration B.21

Design code performance against housing design standards

Below are the relevant housing standards from Module C which need to be met in order to accord with this design code.

C1 Shaping Good Places

C1.1 Response to character and context

-

Proposal should be subservient to the surrounding building, unless it is demonstrated that the form of the building would not negatively impact on the character of the street or amenity of neighbouring properties.

-

Frontage line at ground floor should align with the back of the pavement to maximise use of site footprint.

-

Two storeys allowed above street level.

-

Upper level must be set back from the street.

-

Basement level allowed if there is no risk of flooding.

-

Proposals should demonstrate how materials and fenestration have been used to reference surrounding scale.

C3 From Street to Front Door

C3.1 Access and servicing

- Refuse store accessible from the street.

- Refuse store to be integrated into building form.

- Emergency access should be provided from the street.

- Residential access should be provided from the street.

C3.2 Safety and security

- Improve natural surveillance of the street through entrance and aspect.

C3.3 Cycle parking

- As a minimum, cycle parking must be provided in accordance with the London Plan Policy T5 and guidance contained in the London Cycling Design Standards.

C3.4 Car parking

- Parking should be provided at or below the maximum standards set out in London Plan Policy T6.1, including provision of disabled persons parking where applicable.

C4 Dwelling Space Standards

C4.1 Private internal space

- All dwellings must meet London Plan space standards.

C4.2 Private outside space

- Must meet minimum London Plan requirements.

- There should be no projecting balconies.

- Proposals should demonstrate how private open space has been integrated.

C4.3 Spatial quality

- Proposal should demonstrate high quality internal spaces that achieve good levels of daylight and sunlight, aspect and privacy, despite the constraints of the site.

C5 Home as a Place of Retreat

C5.1 Privacy

-

Primary aspect should be towards the street.

-

All other facades should consider mitigation of overlooking of neighbouring properties.

-

Roof lights should be considered.

C5.3 Daylight, sunlight and overshadowing

-

Access to natural daylight should be maximised while preserving privacy for neighbouring properties.

-

Use of roof lights may contribute to this.

-

Building orientation and glazing should reduce the risks of overheating and support energy efficiency in use.

C6 Living Sustainably

C6.1 Environmental sustainability

-

Use sustainable materials.

-

Ensure high levels of fabric efficiency and energy efficient fixtures and fittings to reduce energy demand.

-

Supply energy efficiently and cleanly, and maximise opportunities for renewable energy where possible.

-

Overheating risk should be designed out and the need for active cooling avoided.

-

Developments must meet the Air Quality Neutral benchmarks. On smaller housing developments, the building benchmarks can be met by using ultra- low NOx boilers or other less polluting technologies, which could include heat pumps, connection to an existing district heating scheme, fuel cells or renewables (excluding biomass).

C6.2 Biodiversity and urban greening

- Urban greening (e.g. green roofs, green walls, street trees) should be used to ensure that there is no net loss of green cover. This greening also addresses local environmental needs such as mitigating flooding or urban heat, improving air quality or enhancing biodiversity.

C6.3 Flood Mitigation and SuDS

- If within a high flood risk area, incorporate property flood resilience measures.

- Incorporate sustainable drainage.

C6.4 Air pollutant emissions

- Car-free developments are assumed to meet the transport emissions benchmark.

C7 Future Proofing

C7.3 Quality, maintenance and management

- Developments should be constructed from materials that are robust, high quality, and reference the context.

5. Contributors and Thanks

This suite of guidance documents has been led by GLA’s Planning team

with the input and support of the GLA’s Housing and Land, Environment and Regeneration teams. It draws on the findings of the Good Growth by Design Housing Design and Quality of life Inquiry and input from a range of contributors including the Stephen Lawrence Trust and Urban Design London members. The guidance documents have been prepared by a consultant team led by Mae Architects Ltd in close liaison with the GLA.

Mae Architects Ltd team included CMA Planning, Max Fordham, Point 2, Dhruv Sookhoo, Pamela Buxton, Atwork

The GGbD Sounding Board was comprised of Claire Bennie MDA, Dipa Joshi MDA, David Ogunmuyiwa MDA, Julia Park MDA, Neil Smith MDA, Manisha Patel MDA, Dinah Bornat MDA, Rachel Bagenal MDA, Jo Negrini LB Croydon, Andy Reid Fairview Homes, Esther Kurland, Urban Design London.

References

- Reference:1Guidance relates to the following policies within the London Plan (Greater London Authority, 2019): Policy D1: London’s form, character and capacity for growth, Policy D2A: Infrastructure requirements for sustainable densities, Policy D3: Optimising site capacity through the design-led approach, and D4: Delivering good design (Policy H2: Small Sites).

- Reference:2Good Growth by Design: A Built Environment for All Londoners (Mayor of London, 2017).