Key information

Publication type: Consultation

Start date: Friday 9 May

End date: Sunday 22 June 2025

Contents

9 sections

How to comment on this document

Mayor’s Foreword

Throughout history, London has evolved to meet the challenges presented by each new age – and we must do so again if we are to ensure every Londoner can afford somewhere they can call home.

This document sets out a path towards my next London Plan, the strategic framework that will guide and shape our city’s development in the years ahead.

The next London Plan will be a blueprint for how we can continue to build the fairer, greener city that Londoners deserve. It will aim to make the best possible use of City Hall’s planning powers to achieve two key objectives. These are to fix the housing crisis in London and deliver sustainable economic growth that benefits Londoners across our city, all while ensuring we continue to meet our ambitious climate commitments and improve our environment and green spaces.

Since 2016, we have worked hard to get London building again. We hit the target of starting 116,000 new genuinely affordable homes, and have also ushered in a new golden era of council housebuilding, taking council homebuilding to the highest level since the 1970s. That’s double the rate of the rest of the country last year combined. However, we now face a difficult period for housebuilding in the capital. This is due to a lack of national funding by the previous government and the economic legacy of low-growth, high interest rates and the rise in the cost of construction materials.

When I was elected for a third term as Mayor, I said I wanted to make London the best city in the world to grow up in and to ensure all Londoners have the chance to reach their potential. To do this, we must do everything we can to build the affordable homes to buy and rent that Londoners desperately need.

At present, over 90,000 children are officially homeless and living in temporary accommodation in London. Tens of thousands more are in overcrowded housing. Young couples are having to move out of London to afford a family home. And high housing costs are increasingly becoming a barrier to moving to London to study or work in the first place. We cannot let this continue.

Addressing the housing crisis will also be critical to growing our economy, increasing productivity, raising living standards and reducing inequality in our city. That’s why, working with local councils, business, and others, we have put affordable housing and the built environment at the heart of our new growth plan for London. We know that good quality housing is not only essential for Londoners, but for attracting and retaining talent, unlocking employment opportunities, and revitalising neighbourhoods.

Our previous London Plans have helped us to increase the number and quality of new affordable homes in London. But given the scale of the challenge we now face and our bold plans for growth, the next London Plan will need to go further.

The government has said London needs 88,000 new homes per year. So the next London Plan needs to plan for 880,000 homes, ten years’ supply. This is far more than we have ever built before. London has only ever built at anything approaching this rate in the 1930s when there was a housing boom across the country. A large percentage of Londoners today live in the homes built during this time, particularly in outer London.

It's clear we face an extraordinary challenge, but one we must do everything we can to meet. We have no time to waste. That’s why, in the short-term, I want to see local planning become more flexible and focused on securing permissions for housing development.

I also want to ensure we look at how we can make better use of the land we have, take opportunities to increase the density of housing developments and work with local councils to substantially increase the rate of building in every borough.

My preference will always be for us to secure as many new homes as we can on brownfield sites – both large and small – and ensuring that delivery is accelerated wherever possible. But this alone will not be enough. That’s why the government has changed the national policy on potential development sites. This includes cities and local authorities exploring the potential release of parts of the green belt for development, particularly lower quality land.

As Mayor, I want to ensure that any release of the green belt to help address the housing crisis makes the best use of land and meets strict requirements. This includes maximising the level of affordable housing; ensuring high-quality housing design and good transport connectivity; and increasing biodiversity and access to good-quality green spaces as part any developments. The truth is that some land designated ‘green belt’ in London is low quality, poorly maintained and rarely enjoyed by Londoners. If built in the right locations, with close access to public transport infrastructure, new developments on parts of the green belt could deliver tens of thousands of new affordable homes for Londoners. They could also help to reduce carbon emissions, improve the quality of our green spaces, and increase biodiversity.

To achieve these aims of building more affordable homes, unlocking economic growth and increasing access to good-quality green spaces, the London Plan must become more streamlined and focused. This will remove duplication of national policies where these are equally relevant to our city. In some cases, we will need to go further than national guidance, recognising the unique challenges and opportunities of a global city like London. But in doing so, we must carefully consider the impact of policies on the costs and viability of new developments to ensure we don’t hamper growth.

It’s important to note that this is a consultation document, which looks at different options, trade-offs, and some potentially difficult choices. Not everything in this document can or will be taken forward.

I hope you consider the options we set out carefully and encourage you to take part in the consultation as we work towards our next London Plan. This will help us to build a brighter, fairer, and more prosperous London for everyone, where no one is left behind.

1. Introduction

1.1 What is the London Plan?

The London Plan is a document prepared by the Mayor of London. It is the strategic, spatial plan for Greater London, setting out the strategy and requirements for homes, jobs, transport, and other infrastructure, as well as policies to ensure quality development. It has two roles relating to the planning system:

- Policies in the London Plan are used to help shape and determine development proposals for all planning applications across Greater London, and any conditions or legal obligations that may be applied. The London Plan is part of the ‘development plan’ together with the local plan for the area and any neighbourhood plans. Planning applications must be determined in accordance with the development plan unless material considerations indicate otherwise.

- When local authorities write their own plans, they must be in ‘general conformity’ with the London Plan. This broadly means that the local policies can’t harm implementation of the London Plan.

The London Plan must be reviewed every five years. The current plan was published in March 2021. We will publish a draft new plan in 2026 for consultation.

1.2 What years will the new London Plan cover?

The new London Plan will run from adoption in 2027 to 2050. This enables us to properly plan ahead, particularly given that things like major transport infrastructure take many years to plan and deliver.

For housing targets, the plan will run from 2026-27 for 10 years. Many of the measures needed to increase housing supply need more time to put in place, so measures needed beyond 10 years will also be planned for.

1.3 How many homes will it plan for?

London's population has grown by 1.5 million over the last 20 years, reaching a record high of almost nine million by 2023. Though growth has slowed in recent years, London's population is still expected to rise by a further million over the period covered by the next plan. A huge increase in housing delivery is needed both to accommodate future growth and to address the chronic shortage of homes for existing residents.

New rules have been put in place about how much housing different areas in England have to plan for. In London, we have been told by the government that housing need in London is 87,992 new homes per year.

Unlike other parts of the country, the London Plan sets housing targets for each borough to achieve. This is based on where those homes can be built, rather than necessarily where the need for those homes arises locally. This means we can better plan where new development happens and make it more likely we can meet London’s overall housing needs. For planning, London is treated as one large housing market.

1.4 Viability and delivery

There are a significant number of development sites across London and a large pipeline of new housing schemes which have received planning permission. However, there are a range of challenges currently affecting housing delivery in London. These include the increase in construction costs seen in recent years, labour shortages in the construction sector, the impact of higher interest rates, a shortage of national government funding, recent regulatory changes, market absorption rates and general economic uncertainty. Together, all have impacted the pace of housing delivery. In some cases, new housing developments which were in the process of being built have stalled, leaving partly built developments on vacant construction sites.

There are indications that market conditions are improving, and London has a proven track record of being a very adaptable and resilient city. However, the new London Plan will be produced at a time when challenges will remain.

It is vital that we have an ambitious approach to quality, and we continue to deliver key objectives, like meeting our climate commitments and increasing inclusion, health, and wellbeing. In doing so, we must carefully consider the impact of policies, individually and cumulatively, on the costs and viability of development. Much is expected of what can be delivered through the planning system. At the same time, there are also constraints in terms of the cost of building homes, workplaces, and infrastructure.

The policies adopted in the plan will need to be considered in this context, as well as across the overall plan period. This will be informed by an assessment of the viability of development, and the delivery approaches that best support an increase in housing supply for London and the provision of sustainable development.

The London Plan will need to identify the capacity to deliver 880,000 homes over 10 years and how we can achieve Good Growth. It will also need to show that the policies in it are viable in the context of our ambition to accelerate housing delivery. However, it is not a delivery plan: there are many other factors that will need to be in place alongside the plan. These include funding for affordable housing and transport, and the delivery of sufficient energy, water, education and healthcare and other infrastructure capacity needed.

The next London Plan will not increase the overall burden of planning policy requirements on development under the current circumstances. Opportunities will also be taken to streamline requirements and speed up consideration of planning applications. Some policy requirements may be phased so they start to apply at a later date or, for example, when economic conditions or technologies improve.

1.5 What is this document about?

This document sets out key new ideas that the new plan might include for you to consider and comment on.

It is important to note that it does not include all of the policy matters covered by the current London Plan. This document focuses on a range of more significant potential options and changes. However, there will still be changes that will affect the rest of the plan, including the wording and other technical changes to make an existing policy work better. You are welcome to comment on any matters relevant to the next London Plan, whether they are covered in this document or not.

The document sets out a range of options for consideration and discussion, but not all of them will be taken forward in the final plan.

It builds on the engagement we have been doing since December 2021 which includes:

- In-person all-day ‘deliberative events’ with groups of Londoners, independently selected to be representative of the city’s wider population. These explored key dilemmas facing London, including where new housing could be built and related aspects of transport, the economy and environment.

- Stakeholder events open to all, exploring similar themes to the deliberative events.

- Co-design events and programmes run by the London Sustainability Commission, New London Architecture and the London Housing Panel.

- Engagement with young Londoner’s through the Mayor’s Design Future London programme.

- Online engagement via Talk London, City Hall’s online community, the GLA engagement portal and a call for evidence through the GLA website.

Read more about the engagement process here.

Many of the issues covered in this document are challenging and have been included to stimulate discussion about difficult choices. Some of the options come from earlier engagement and feedback. The options do not necessarily represent the Mayor’s views or preferred direction.

The document also sets out some key issues raised since the publication of the current London Plan. These include significant concerns voiced by the government and developers about the difficulties of delivering new homes and the necessity for change to increase housing delivery. Equally, it explores how we can ensure the quality of development and the environment and make London an even better place to live, work and enjoy.

In some cases, it may be possible to target policies better or streamline how they are applied to reduce costs and speed up the planning process. Other choices will be more fundamental. This is particularly important where new national approaches have been put in place since the current plan was written.

For some issues, such as the need to have a credible plan for 880,000 homes, we have indicated a proposed direction. For others, there are clear choices about the future approach, and we are seeking to reflect the different views, considerations and options for discussion and views. The Mayor is keen to hear from Londoners and stakeholders about what their priorities are and where the balance should lie.

How is a new London Plan prepared?

1.6 Legal and procedural requirements

Before it can be adopted, the London Plan must meet a number of requirements. These will be tested by Planning Inspectors at an independent examination. The plan must also be agreed by the Secretary of State and the London Assembly.

Legal and procedural requirements include:

- consultation

- supporting assessments (see below)

- evidence

- viability testing of the plan as a whole

- coordination with neighbouring authorities

During the examination, the Inspectors will check the plan is ‘sound’. That means it is:

- Positively prepared – a strategy which seeks to meet London’s needs as a minimum. It also coordinates with authorities outside London and provides for their unmet needs as well (for housing or workplaces for example) where this is practical and achieves sustainable development.

- Justified – an appropriate strategy, taking into account reasonable alternatives, and based on proportionate evidence.

- Effective – deliverable over the plan period. It is also based on effective joint working to deal with cross-boundary matters.

- Consistent with national policy – the plan enables delivery of sustainable development in accordance with national planning policies.

1.7 Integrated Impact Assessment (IIA)

The IIA will support the plan. There may be changes to how this is done in future due to changes to legislation in 2023, but these changes have not been brought in yet. It covers:

- Sustainability Appraisal – considering social, economic, and environmental impacts. The Sustainability Appraisal also includes the Strategic Environmental Assessment which is required by law, and focuses on environmental impacts.

- Equalities Impact Assessment – assessing impacts in relation to the Public Sector Equality Duty.

- Health Impact Assessment – assessing impacts on health and health inequalities.

The IIA is a series of assessments prepared throughout the development of the plan. The first stage is the Scoping Report. This sets out baseline information so the impacts can be assessed and what objectives the plan will be measured against.

The IIA Scoping Report will be published later this year.

1.8 Habitats Regulations Assessment (HRA)

This considers whether the plan is likely to have a significant effect on a protected habitats site (either individually or in combination with other plans or projects) as set out in national policy. This will be prepared and published with the draft London Plan.

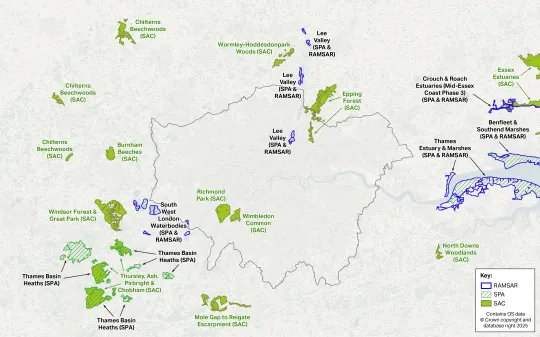

Sites relevant to the Habitat Regulations for London

Figure summary: Map including the following: Special Areas of Conservation (SACs) wholly or partly within London: Richmond Park, Wimbledon Common and Epping Forest. Special Protection Areas (SPA) and Ramsar sites wholly or partly within London: Lee Valley and South West London Waterbodies. SACs outside London: Burnham Beeches, Mole Gap to Reigate Escarpment, Wormley-Hoddesdonpark Woods, Windsor Forest and Great Park and Thursley, Ash, Pirbright and Chobham. SPAs outside London: Thames Estuary and Marshes (also Ramsar) and Thames Basin Heaths.

1.9 Beyond London

National government is making many changes to the planning system and this will impact on the development of the London Plan. This includes changes to national policy, housing requirements and new national development management policies which will supersede London Plan policies that cover the same matters. The government will also be introducing strategic planning across the rest of England. These will align better with the strategic planning already in place in London through the Mayor of London and Greater London Authority (GLA).

London also has inextricable links with the neighbouring regions, the South East and East of England. The government is proposing the South East region delivers 71,000 homes per year and the East of England deliver 45,000 homes per year. Together with the requirement for London of 88,000 homes per year, these three regions are expected to meet 55 per cent of the housing delivery for England. There may be opportunities for joint work to plan for growth across London’s boundary.

Progress on the current London Plan

1.10 Good Growth objectives

The current London Plan is based on Good Growth – growth that is socially and economically inclusive and environmentally sustainable. It is informed by six Good Growth objectives as set out in the current London Plan:

- Building strong and inclusive communities

- Making the best use of land

- Creating a healthy city

- Delivering the homes Londoners need

- Growing a good economy

- Increasing efficiency and resilience

Find out more about Good Growth objectives here. As the Mayor has highlighted, delivering the homes Londoners need and growing a good economy are critical priorities for this next London Plan. At the same time, it remains vital to build strong and inclusive communities, help to tackle the climate crisis and ensure a healthy and resilient city. Overall, these remain sound principles to underpin the next London Plan, but nevertheless we welcome comments and views on these key plan objectives.

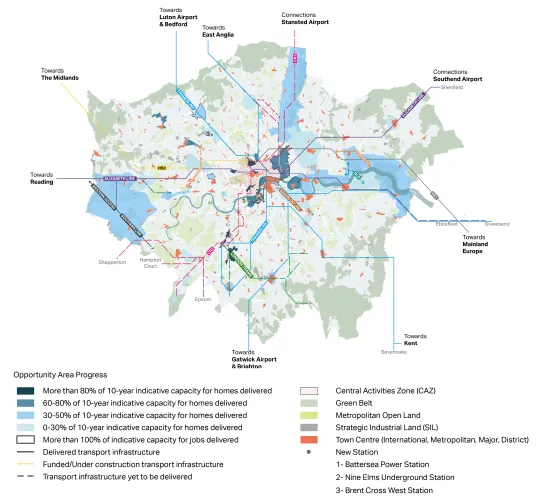

1.11 The Key Diagram

The current London Plan has a Key Diagram, showing the spatial vision for the plan. The figure below shows the progress that has been made on that vision. This includes:

- progress against indicative capacities for housing and jobs in Opportunity Areas

- completed transport infrastructure - Elizabeth line, Thameslink, Northern line extension to Battersea, London Overground extension to Barking Riverside, the Silvertown Tunnel, High Speed rail to Mainland Europe and new stations at Battersea, Nine Elms and Brent Cross West

- transport infrastructure projects that are under construction - High Speed Rail 2

The diagram also shows transport infrastructure projects that remain unfunded or have not yet progressed. This includes Docklands Light Rail (DLR) extension across the Thames to Thamesmead and Abbey Wood, the Bakerloo line extension to New Cross, Lewisham and Catford, the Overground extension between Wembley and the Great West Corridor (now referred to as West London Orbital), London Trams, Western Access and Southern Link from Heathrow and Crossrail 2 linking Surrey with Hertfordshire running from the south west to north east of London.

As the Mayor highlighted in the London Growth Plan, we will need to extend and upgrade the public transport network. Key initial priorities include the DLR extension, West London Orbital, metroisation of suburban rail and the Bakerloo line extension (see section 4.3 below). The role of these and other projects will be identified alongside the development of the next London Plan’s spatial vision.

Progress on the London Plan - Key Diagram

Figure summary: Key Diagram from the 2021 London Plan annotated to show the progress against the indicative capacities and transport infrastructure committed to in the current Plan. The illustration highlights the following: Opportunity Areas with more than 80% of their 10-year indicative capacity for homes delivered include the Wimbledon/Colliers Wood/South Wimbledon, Victoria, Tottenham Court Road, Euston and Paddington Opportunity Areas. Opportunity Areas with between 60-80% of their 10-year indicative capacity for homes delivered include the City Fringe/Tech City, Waterloo, Vauxhall Nine Elms Battersea, Canada Water and Wembley Opportunity Areas. Other Opportunity Areas with less delivery are also shown. Transport infrastructure projects which have been delivered, funded, under construction and yet to be delivered are also highlighted.

2. Increasing London’s housing supply

London has been delivering between about 30,000 and 45,000 homes a year for the last decade, rates of housing delivery not seen since the 1970s. This includes market and affordable homes, as well as specialist housing like student housing or homes for older people. This has however slowed recently due to several factors including rising construction costs, interest rates, a lack of national funding by the previous government and inflation, and uncertainties about how buildings should be designed, such as new fire safety regulations.

The government has set out new national requirements for the number of homes to be delivered across England. Over the ten-year period of the next London Plan, the government has said the housing need in London is 880,000 new homes. They have also changed the approach to the green belt. London will be required to review and release green belt to meet housing and other development needs where those needs cannot be met in other ways, such as redevelopment within London’s existing built area.

For London, this increase is very significant (over double the current rate of housebuilding) and requires new approaches to building homes beyond the current mechanisms. London has only ever built at anything approaching this rate in the 1930s when there was a major expansion of London’s built-up area. This was driven by the rapid extension of the transport network, very low interest rates and other factors very different to today.

Estimated number of homes built per year in London (1871 to 2023/24)

Figure summary: graph showing housing development between 1871 and 2023/24, with a peak at 80,612 in 1934, 78,838 in 1936, 75,676 in 1935, dropping to 55,512 in 1931. The peak in recent years was 45,676 in 2019 and 44,366 in 2016. The previous peak before this was 37,436 in 1970. That peak, between 1960 and 1979, was made up of a very high proportion of local authority building.

Achieving this level of housebuilding is clearly not just about the London Plan, or even planning more widely. It involves a range of other significant factors. For example, economic conditions, the availability of workers and materials, whether people can afford the homes once they are built, funding for affordable housing, and the delivery of the right supporting infrastructure.

Different types of housing and housebuilders are needed to accelerate and increase supply. There is a limited ‘effective’ demand for newly built market housing (because many people, while they need a home, cannot afford to buy). It therefore tends to be built and phased to match demand and maintain the values agreed at planning application stage. Building affordable housing can increase supply because there will always be people who need those homes. This will rely on increased public subsidy, especially as affordable housing providers are increasingly needing to invest in improving the condition of their existing homes. Diversifying housebuilders such as small and medium housebuilders, build to rent providers, government, councils, and other public sector landowners can also help increase housing supply. The GLA is working with the government and partners on ways to increase the build rate.

The Mayor is clear that achieving higher rates of housebuilding also depends on funding for vital transport improvements to unlock additional capacity for these homes. Higher volumes of development, as well as its sustainability, critically depend on good public transport connections and a high-quality safe environment for walking and cycling. This principle will underpin the new London Plan because development that is not dependent on cars can deliver significantly more homes on the same area. It makes best use of precious land, while also underpinning ambitions to reach net zero.

These issues and challenges will need to be addressed. Alongside this, we need to put a new London Plan in place that sets out how we can plan for 880,000 homes or ten years’ supply, as required by the government. Being able to build this scale of housing over the decade from 2027 would need planning permissions in London to reach even higher numbers sooner and remain at that level. This is because there is a significant time-lag in getting homes built. But we must get plans in place now to build towards delivery and bring forward as many homes as possible as early as possible.

2.1 A brownfield first approach

The London Plan will prioritise opportunities to plan for and deliver homes within London’s existing urban extent first. This includes positive policies, identifying land supply and other measures to increase the build rate and ensure that the homes are built in the right places, supported by public transport. The following sources of housing all need to be optimised to make the biggest contribution possible towards 880,000 homes.

Increased density will need to be part of the solution and this document sets out key options to consider in this section and Section 4 below. Alongside this, the London Plan will need to ensure the quality of places and be clear about what is needed to support higher density living. Much of this development potential is linked to public transport improvements and, in many areas, cannot be realised without funding for this.

Current brownfield housing delivery and new national housing need

Figure summary: Graph showing the current contribution from the different housing sources described in paragraphs 2.3 to 2.7 below, and the cumulative amount of housing this would provide at 400,000 homes compared to the national housing need figure of 880,000 homes.

2.2 London’s call for sites - LAND4LDN

London’s call for sites was launched in autumn 2024 and over 750 sites were submitted by developers, landowners, boroughs, and members of the public. We have also worked with boroughs to bring together all their information about housing land supply, and how this has changed since 2017 (when it was last done).

These sites are being assessed to estimate how many homes they might deliver. The site information will also be used to help model how different policy levers might impact housing delivery.

These include existing permissions for over 250,000 homes on large sites that have not been completed. It also includes sites that have been identified and allocated by London’s planning authorities. The Mayor is working with boroughs and the government to unlock as much of this as possible.

2.3 Opportunity Areas

Opportunity Areas (OAs) are areas with the potential to deliver a substantial amount of new development to provide homes and jobs. The first 28 OAs were defined in 2004 and there are 47 OAs in the current plan.

About 250,000 homes have been built in London’s OAs over this 21-year period, with almost 100,000 of these homes being completed within the current London Plan monitoring period (from 2019-20). However, there are also over 200,000 homes with planning permission which have yet to be built (shown in Figure 2.2 above). We are now working to understand how many of these could be built over the next London Plan period, and what mechanisms and investment are needed.

OAs are different from each other in terms of their mix of uses. Some, for example, are focused on economic growth and employment as well as housing. OAs have different infrastructure requirements, timescales for delivery, and local context and communities too. They also have different stages of maturityReference:1.

In the current London Plan, OAs are grouped under eight broad areas, principally related to significant transport infrastructure investment such as the DLR extension, Bakerloo line extension, and High Speed 2. The Mayor is clear that many of the homes and jobs planned in the Opportunity Areas can only be realised if the transport infrastructure is built, unlocking viability, higher densities and ensuring sustainable development. The GLA is working with the government and boroughs to look at how these can be funded and bought forward.

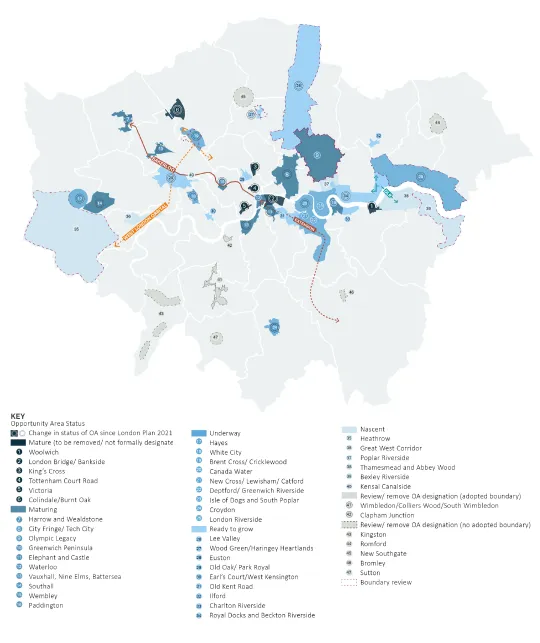

The new London Plan will consider streamlining and updating the status of the OAs, as shown in Figure 2.3 below, for example, because OAs are now mature. It could also de-designate some OAs because circumstances have changed, and they are no longer very different from other town centre and London locations. This will include considering how to deal with areas where transport infrastructure schemes are now less certain or will only be delivered beyond the next decade (for example Crossrail 2, a new train line from Enfield to Kingston, that will be similar to the Elizabeth line).

We will also explore whether and how the government’s New Towns Taskforce work might apply within London’s current urban area to certain OAs of significant scale. This includes asking whether this would bring any additional benefits to the approach.

Potential changes to Opportunity Areas

Figure summary: map showing London’s Opportunity Areas with the following changes to current status: 1) Maturing becomes Mature: proposed for Woolwich, London Bridge/Bankside, King’s Cross, Tottenham Court Road, Victoria and Colindale/Burnt Oak. 2) Underway becomes Maturing: proposed for Harrow and Wealdstone, City Fringe/Tech City, Olympic Legacy, Greenwich Peninsula, Elephant & Castle, Vauxhall, Nine Elms & Battersea, Southall, Wembley and Paddington: 3) Ready to grow becomes Underway: proposed for Hayes, White City, Brent Cross/Cricklewood, Canada Water, Croydon and London Riverside: 4) Nascent becomes Ready to grow: proposed for Lee Valley, Wood Green/Haringey Heartlands, Old Oak/Park Royal, Royal Docks and Beckton Riverside; 5) Review/remove OA designation: proposed for Wimbledon/Colliers Wood/Morden, Clapham Junction, Kingston, Romford, New Southgate, Bromley and Sutton.

The current brownfield housing figure for Opportunity Areas shown in Figure 2.2 above is based on the delivery of key transport improvements. These need the DLR extension to Thamesmead and Abbey Wood to unlock an additional 25,000 to 30,000 homes and the Bakerloo line extension to Lewisham and onto Catford, Hayes and Beckenham Junction to unlock an additional 20,400 homes (and there may be scope to deliver more). Other mechanisms outside planning will also be needed to unlock some of these areas and bring forward development.

We would welcome views on this alongside evidence from implementation of OAs. In particular, we’d like to hear if any other areas should be considered for new OAs and are there other levers that could help us realise their potential.

2.4 Central Activities Zone

The CAZ needs to continue to function as the UK’s economic powerhouse and at the forefront of London’s global city offer (as set in Section 3 below).

Within this context, London’s Central Activities Zone (CAZ), including the Northern Isle of Dogs, has almost 300,000 residents. Around 4,000 new homes are delivered here annually, almost one in every 10 homes across London (shown on Figure 2.2 above). This trend is expected to continue.

The scope to significantly increase delivery beyond this may be limited by a range of factors. These include challenges around affordability and the need for development capacity for commercial activity. In addition, we must also manage the risk of new residents seeking to restrict the functioning of the CAZ due to noise and disruption.

Constraints imposed by London’s strategic views and their viewing corridors have also been raised by stakeholders. The Mayor is clear that valued strategic views will continue to play an important role in protecting London’s heritage, the ability to appreciate it and its contribution to London. London’s viewing corridors also converge on key assets such as St Paul’s Cathedral. This means that changes to one corridor do not necessarily create additional development capacity because the land lies under several viewing corridors. We are currently reviewing the guidance set out in the London View Management Framework to bring it up to date. We could also consider more detailed aspects and how the policy works in practice to ensure its impact is proportionate.

Within this there will continue to be a role for housing. Some areas, such as Kings Cross, have now redeveloped much of their supply of land. Other areas, such as the Northern Isle of Dogs, may become more mixed in future, bringing new opportunities such as increased housing. The London Plan could consider whether amendments should be made to the CAZ boundary to better match areas with a concentration and mix of uses which is unique to the CAZ. This would exclude areas that are mainly residential in character which instead could play a greater role in housing delivery. There may also be opportunities for re-purposing lower grade office stock for housing in appropriate areas or for more affordable workspace or other uses.

2.5 Town centres and high streets

London’s town centres and high streets have a mix of uses including many homes and residents, often above commercial premises. These locations often have good access to public transport and provide a denser, walkable urban environment. Across London, about 7,700 homes are delivered every year in town centres and high streets, often with shops or other active uses at ground floor. Of these, about 5,300 are also in Opportunity Areas. These past trends are reflected in Figure 2.2 above.

The potential of our town centres and high streets to increase their contribution to housing is set out in this document. This is particularly in relation to increasing densities where there is good access to public transport (see Section 4 below).

2.6 Industrial land

The current London Plan allows co-location of homes and substitution of land in some circumstances, to enable homes to come forward alongside industrial uses and land swaps to release land for housing. Over the current plan period, since 2019-20, an estimated 4,500 homes a year were given planning permission in co-location schemes. However, less than 40 percent are currently under construction or built.

Over the last 10 years, an average of 1,500 homes a year have been delivered on designated industrial land, as shown in Figure 2.2 above. However, over the current plan period about 4,500 homes a year have also replaced industrial uses on land not designated for industrial.

However, around 18 per cent of London’s industrial use has been lost since 2001, and this rate is not sustainable. London needs sufficient industrial capacity to meet business needs and enable our city’s economy to function and grow.

Nonetheless, it may still be possible to deliver homes from this source. There may, for example, be opportunities to provide additional, or swap, industrial capacity in London’s grey belt - especially in locations that are less suitable for housing. For example, areas with high noise levels or better connections to the road network rather than public transport. This could allow some well-connected brownfield sites to be released for housing. A strategic, London-wide approach to London’s industrial capacity, as we set out later, could also allow the need for industrial capacity to be met in locations that are most suitable. This would free up sites that are less suitable and make a greater contribution to housing.

2.7 Wider urban and suburban London

About 14,400 homes a year are delivered across London’s neighbourhoods, outside the designated areas set out above. The current London Plan has a particular focus on small sites within 800 metres of a town centre or station, and this source of housing makes up most of these homes (about 12,000 homes a year). The rest are either from large sites or small sites that are further away from stations and town centres. This is reflected in Figure 2.2 above.

There have been different approaches to intensifying existing urban neighbourhoods, often set out by boroughs in planning guidance. Some have encouraged extensions to existing homes or using land between or beside existing housing to provide new homes. Other guidance has gone further to support the redevelopment of single homes for a significantly larger number of homes on the same site.

There is also a range of under-used sites such as low-density retail parks and car parks which offer potential for housing / mixed uses.

As this document sets out, we are considering various opportunities and approaches to bring forward more homes in the next plan. We are also assessing possible improvements to public transport to support these opportunities. This includes extending current lines, strategic bus services and providing more metro-type services on (current) National Rail lines (replicating the success of London Overground).

2.8 Other sources of housing supply

The current London Plan expects all housing supply to come from sites that are not designated as Metropolitan Open Land or green belt. This was based on a need for 66,000 homes per year and a housing target of 52,000 homes per year. Current delivery rates are below 40,000 homes a year. Even a big increase from brownfield supply will not deliver 88,000 homes a year wholly within London’s existing urban extent.

New national policy means that the green belt should be reviewed. This includes altering green belt boundaries to meet London’s housing need in full if it cannot be met in other ways.

Therefore, in line with the government’s requirements, the Mayor has commissioned a London-wide green belt review. He is clear that any green belt release should be based on building sustainable, liveable neighbourhoods with access to public and active travel options, making the best use of land. It must also deliver improved access to green space and nature (potentially including a new generation of enhanced or new public parks for Londoners subject to funding) and gains in biodiversity.

2.9 Beyond London’s existing urban area

National planning policy and guidance introduces a new concept of ‘grey belt’. These are green belt areas that have either been previously developed (PDL) or don’t strongly contribute to any of the three green belt purposes:

- to check the unrestricted sprawl of London

- to stop neighbouring towns merging into one another

- to preserve the setting and special character of historic towns.

The strategic green belt review will include identifying ‘grey belt’ land across London. This will help understand the potential capacity from housing on London’s grey belt, and other uses, as part of strategic planning for different land uses. These include industrial capacity, data centres or energy and other infrastructure.

2.10 Large-scale urban extensions in the green belt

Given the government’s proposed approach to the green belt, the Mayor is clear on how any homes in London’s green belt should be delivered. They must be focused on creating affordable, well-planned, well-connected neighbourhoods with densities that support public transport and a local economy. These would also be expected to meet the new national ‘golden rules’ for green belt development including affordable housing, infrastructure and new or improved accessible green spaces.

Opportunities for large-scale development (10,000+ homes in each location) in London’s green belt are being considered in areas with good public transport access (or where this could feasibly be delivered). There is also significant potential with the government’s New Towns Taskforce, which we will be engaging with. However, any new homes delivered would need to count towards, not be additional to, meeting London’s nationally-established housing need of 88,000 homes per year.

We are also starting to explore at a strategic level potential new public transport that could unlock further housing capacity. This includes, for example new stations, increasing rail frequencies, and possibly extending existing lines. It is important to note that there are no proposals yet and any schemes have not been tested. We must also be careful not to divert the investment needed for transport improvements to support brownfield development.

A strategic approach will also be needed to join up consideration of green belt development and these large-scale settlements with the Local Nature Recovery Strategies (LNRS) and other programmes and opportunities. The green belt’s original purpose was to prevent urban sprawl. This is still reflected in national policy today. However, our approach now must be allied with a clear focus on supporting nature and the environment and improving access to good-quality green spaces for Londoners. Large-scale urban extensions could enable us to deliver a programme to enhance, expand or establish regionally protected parks (Metropolitan Open Land) and other open spaces accessible for Londoners (as part of an overall infrastructure package with available funding), boost biodiversity outcomes and improve nature in other ways.

South East green belt with Greater London boundary

Figure summary: Map of London’s green belt and including the Greater London Authority boundary showing that most of the green belt is outside the Greater London area.

2.11 Metropolitan Open Land

London relies heavily on its designated open spaces to create a liveable city. Metropolitan Open Land (MOL) is the strategic level of open space, designated with specific criteria in mind. Unlike green belt purposes, MOL criteria does involve environmental considerations.

The Mayor will continue to give protection to MOL given its vital role for Londoners and providing a liveable city as London grows. However, some areas of MOL, such as certain golf courses are not accessible to the wider public and have limited biodiversity value. This undermines the purpose of the designation. These areas could be assessed to understand whether they should be released from MOL. They may be able to help to meet London’s housing and accessible open space provision (for example opening up strategic new open spaces accessible to Londoners alongside new homes). At the same time, they could improve biodiversity through landscape-led redevelopment. Clearly there are key issues to explore. For example, could golf courses with Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation (SINC) designations be released (with compensatory biodiversity uplift), and if so, in what circumstances.

2.12 Affordable housing

The Mayor is determined to make housing more affordable to Londoners on low and middle incomes. Not having enough good quality affordable homes is impacting Londoners and the capital overall in many ways:

- Over 183,000 Londoners are estimated to be homeless and living in temporary accommodation. Collectively, this is recently costing boroughs about £100m a month.

- Poor housing impacts physical and mental health, with unaffordable (and unstable / low quality) housing linked to increased stress, anxiety, and depression. Poor housing in London costs the NHS an estimated £100m a year due to falls, excess cold and/or heat and a range of other hazards.

- Housing affordability is having an impact on the productivity and growth of the capital. It is estimated that if housing affordability was improved by one per cent, this would create an additional £7.3bn GVA over 10 years.

The current London Plan has played a key role in significantly driving up the proportion and number of affordable homes in recent years. The next London Plan will need to continue to do this.

Council homebuilding has been boosted to the highest level since the 1970s. The ambitious target of starting work on 116,000 new genuinely affordable homes was exceeded in 2023.

However, in recent years, affordable housing delivery has been strained by a challenging delivery environment. This includes:

- a lack of national funding by the previous government

- high interest rates and the increased cost of building homes

- regulatory uncertainty, such as fire safety requirements

- challenges around the quality, building safety and sustainability of existing homes, and insufficient social rent settlements. This limits the ability of social landlords to invest in new affordable homes.

2.13 Planning for affordable housing

A further step change is required to build the affordable and good quality homes London needs. The focus must be on delivering affordable housing, not simply building more market homes. Put simply, even if the rate of market housebuilding significantly increases, house prices will remain unaffordable to most people who need a home.

Affordable housing delivery also plays an essential role in supporting the overall supply and build-out-rate of housing in London. This is because it doesn’t rely on buyers and therefore has an almost unlimited number of potential occupiers. As such, it will be crucial to meeting the ambition of building 88,000 homes a year.

All sources of affordable housing supply will be needed. This includes affordable homes secured through the planning system and those funded through affordable housing grant, by councils or by housing associations, as well as new delivery models.

The Mayor is clear that the London Plan must continue to drive delivery of affordable housing. It is important to note that policies need to work effectively and consistently over time to enable them to be embedded in land values. Within this, the Mayor recognises the current challenging economic and delivery context and scale of the challenge. This will need careful balancing of ambition and practical implementation.

The Mayor’s threshold approach to affordable housing, has helped to embed affordable housing requirements into land values and speed up the planning process. It incentivises developers to provide higher levels of affordable housing by offering a faster and simpler route to approval. To avoid submitting viability information, schemes need to provide 35 per cent affordable housing. This threshold level is higher for public land and industrial land, at 50 per cent. These thresholds also apply to Build to Rent, purpose-built student accommodation and housing for older people.

We will review threshold requirements when developing the next London Plan to make sure that they still provide the right incentives to support affordable housing needs and delivery. This includes identifying whether some types of development are very challenging to deliver. It will also identify where sites might not be optimised due to the requirement to include affordable housing at 10 units. This can have a disproportionate cost in terms of value and delay to the planning application process.

We welcome evidence and experience of implementation to help inform this review.

It is also noted that where different thresholds are set at a local level, this undermines the benefit and incentive of the threshold approach. In practice, this tends to result in delivering less affordable housing. The London Plan could be clearer about the need to consistently apply this incentive across all boroughs to avoid this.

We need to ensure that any green belt development or land released from the green belt delivers significant levels of affordable housing. This must be embedded in land values. National policy requires higher affordable housing requirements to be set for any development in these circumstances. This is some 15 percentage points higher than the highest existing local requirement, up to a maximum of 50 per cent. The London Plan could set this requirement at 50 per cent and could require different proportions of affordable housing types in different areas.

Different types of affordable housing meet different needs, and it is important to get the balance right between low-cost rent and intermediate homes. Low-cost rent are homes available to people on low incomes to rent, usually social housing. Intermediate homes may be to rent or buy and are for people on moderate incomes who cannot afford market homes. Intermediate homes include intermediate rent (provided at a discount to market rent) and Shared Ownership housing, a part-buy part-rent product.

The greatest affordable housing need is for social rent homes. A future approach could put more emphasis on this housing tenure in line with national policy. This includes setting specific targets for social rent and increasing the proportion of social rented homes secured through the planning system.

We welcome evidence and experience of implementation to help inform this approach.

The role of intermediate affordable housing tenures will also be crucial for middle income earners including key workers. The London Plan could build on work already done by the Mayor and introduce Key Worker Living Rent (based on key workers’ incomes) as a new tenure. This would provide more housing options for middle income households and London’s essential workers.

2.14 Estate regeneration

The regeneration of London’s social housing estates can play a valuable role in ensuring existing homes are well-maintained and safe. It can increase the number of new and affordable homes and improve both the quality of housing and the environment homes are located in.

The current London Plan requires full replacement of affordable housing floorspace. As such, the loss of existing social rent homes through estate regeneration schemes has reduced in recent years. However, the current plan only requires social rented homes to be re-provided as social rent if the occupiers have a right to return. If there isn’t a right of return, the floorspace can be re-provided as either social rent or London Affordable Rent. The next London Plan could require full replacement of social rent homes. This would ensure it is based on floorspace, not just where there is a right to return.

We welcome evidence and experience of implementation to help inform this approach.

2.15 Build to rent

To increase the supply of new homes, more diversity is needed in the market. Build to rent is housing purpose-built as a rental product. It is owned and managed for that purpose. This is a way to deliver housing that is not connected to the sales market.

As such, it may help to increase delivery. This is particularly where demand for buying market homes (and therefore the rate at which that housing is brought forward) is constrained by affordability. Build to Rent mainly provides housing that addresses intermediate housing need.

When large housing schemes are built, a much greater number of those homes are sold to Build to Rent providers than individual buyers or small-scale landlords.

Method of sale for new market homes on large developments

Note: Large developments are defined here as 12 or more homes. Build to rent refers to new homes built specifically to be rented and new homes built for sale but sold to large-scale landlords.

Figure summary: Clustered line chart showing Build to rent providers purchases fluctuating but making up a relatively significant proportion of total sales. It shows a significant drop in sales through Help to Buy when the scheme ended (Q3 2022) and corresponding drop in overall sales. It also shows homeowners without Help to Buy and small scale landlords make up a smaller proportion of sales, but making up a more significant proportion since Q1 2024.

The current London Plan specifies Build to Rent schemes as being at least 50 units. However, this limit does not necessarily need to apply. If Build to Rent is to become more important in meeting housing needs, this definition could be expanded to support more diverse types of development.

We welcome evidence and experience of implementation to help inform this approach and if there are other ways to support an expanded role for Build to Rent.

Alongside affordable housing thresholds, there may be additional models to provide genuinely affordable housing as part of Build to Rent developments to explore. These would help meet housing need and align to the delivery and management model.

We welcome evidence and experience of implementation to help inform this approach.

2.16 Other housing options

Ensuring everyone has a place to call home is also about recognising and planning for London’s varied housing needs. Creating truly mixed and inclusive neighbourhoods enables everyone to meet their potential. It also supports vital economic sectors and reduces pressure on the health service and wider private rental sector.

Increasing choice and better meeting people’s specific needs can also help with overall housing delivery, reducing dependency on major housebuilders.

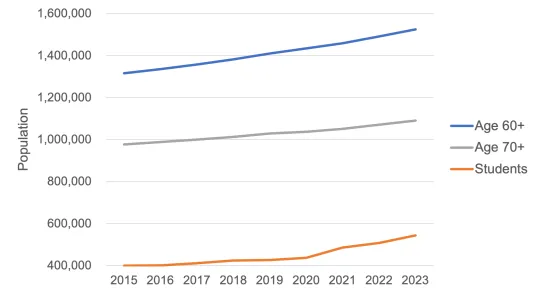

Delivery of many types of more specialised housing has not kept pace with changes in London’s population. These include a large increase in students, a greater proportion of older people, and more people with a disability. New provision has not offset losses of existing stock which may fall short of the standards we expect today. Sometimes this need is hidden as people remain in housing which is not best suited to their needs. In some cases, this housing could better meet other people’s needs.

Population of students and older people in London (1,000s)

Figure summary: Line chart showing the population of older people, 70 years or older, increased from 977,000 in 2015 to 1,090,000 in 2023 and the population of students increased from 400,000 in 2019 to 544,000 in 2023, showing a steeper increase from 2020.

Sometimes, market conditions and other factors can mean that some types of housing (such as co-living) dominate new supply, at least in some areas. Sometimes, housing is aimed at a very particular part of the population (for example, students). When general housing needs are acute, this can raise questions about whether the balance is right or if planning needs to adjust it.

2.17 Specialist and supported housing and housing London’s older population

More flexible housing stock suitable for a wider range of people’s needs and changing household circumstances continues to be an ambition. But we know that there are limits to that flexibility, and sometimes more specialist and/or supported provision is needed. In turn, this provision and choice can significantly improve people’s health and wellbeing, and in some cases free-up much needed family-sized housing.

One challenge is how to know how much of each type of housing is required to best meet the needs of the overall population. The Mayor has heard different views about how best to achieve this. On one hand, defining this at a local level through borough local plans ensures decision-making is informed by local or very specific needs. Alternatively, the London Plan could introduce a more strategic approach to meeting these housing needs to ensure the right housing mix overall across London is delivered. This may be particularly relevant when competition for suitable sites and funding is intense and there may not be a level playing field with general needs housing.

We welcome evidence and experience of implementation to help inform this approach.

Traditionally, planning has made a distinction between someone’s home, and more institutional ways of living and providing care. But in many cases a ‘care home’ may, as the name implies, also be someone’s permanent home, and is distinct from hospital care. It has been suggested that these distinctions, and budget concerns, are getting in the way of best providing for people’s needs. This particularly affects continuity of care and social networks. Different ways of planning for these needs raise important questions about how the care is funded. How do we ensure that provision is available (for example affordable) to all, and how will it be delivered.

We welcome evidence and views about what might be the right approach.

The Mayor is committed to providing housing support for those who need it the most. This includes people who are or have experienced rough sleeping, victims of domestic abuse and those with mental health needs for example.

We welcome evidence and views about what might be the right approach in the London Plan to help meet these housing needs.

2.18 Purpose-built student accommodation and other forms of shared housing

Planning for the right amount of purpose-built student housing, allowing for the fact that some students will always live in conventional housing, can be difficult. Other types of shared housing, whether on a large scale (‘co-living’) or smaller scale (hostels and Houses of Multiple Occupation) can also need similar balancing.

Too much, and these types of development have the potential to crowd-out general needs and family housing. If unmanaged, they can alter the character of an area given their intense occupation. Equally their loss or lack of provision may reduce choice for some people. Purpose-built student housing can provide a well-managed alternative to private renting in a flat share, and can free up those homes for others. It is also critical to support London’s universities and other tertiary institutions and the knowledge sector’s key contribution to London’s economy. However, in some places this makes up most planning applications and development capacity with few other forms of housing coming forward.

HMOs are a relatively affordable form of private rent for some people, although their quality can be a concern. Large-scale co-living developments and student accommodation may contribute important accessible options and wellbeing support which are lacking in the traditional private rental sector.

Given the challenges in balancing these requirements and concerns raised, the London Plan could set this balance and expected quality at a London-wide level (for example, through borough targets or a requirement for site allocations), helping to address the combined impact from many smaller decisions. Or it could be left for Local Plans alone, given this is not an issue felt everywhere. There could also be some aspects left to licensing policy as a more effective way to ensure quality.

We are seeking views as to where the right balance lies.

For specialist student housing, the current London Plan aims to link developments to universities and their student recruitment plans. However, when these are used for market provision (instead of just the affordable rooms), they may create a barrier to delivery. This is because of the commercial risks involved. Therefore, these ‘nominations’ arrangements may be best suited to just the affordable student accommodation.

We welcome evidence and experience of implementation to inform our approach.

More broadly, the London Plan could help balance provision for different needs by ensuring that these housing types contribute to wider affordable housing provision. This would need to address questions about how much should be affordable general housing and how much affordable student or shared housing. It would also be important to set affordable ‘asks’ carefully to avoid unintentionally favouring delivery of some types of housing over others.

We welcome evidence and experience of implementation to help inform this approach.

2.19 Gypsies, Travellers and Travelling Showpeople

While the London Plan requires boroughs to plan to meet need, the number of new pitches being provided remains small. This means it falls far short of what is needed.

Compared with Londoners on average, Gypsies and Travellers are more likely to live in overcrowded accommodation. They also experience worse outcomes in terms of health, employment, and education.

Between 2008 and 2022 there was an estimated loss of around 60 Travelling Showpeople plots. Over this period, the number of boroughs containing Travelling Showpeople yards more than halved, from 14 in 2008 to five in 2022.

London has no transit pitches. This means that currently Gypsies and Travellers and Travelling Showpeople lack legal, safe stopping places, except in places which have adopted negotiated stopping arrangements.

There have been changes in 2024 to a more inclusive definition of Gypsies and Travellers. This now provides a good basis for establishing targets for pitches.

The current plan includes need figures for permanent pitches but does not include targets for permanent pitches and plots as this is left to the boroughs. The new London Plan could set these targets so that there is better provision to meet needs, including where there is competition from other land uses, including other types of housing.

We are seeking views about where the right balance lies.

The plan could also require boroughs to consider granting permanent permission for suitable sites which currently have temporary planning permission. This would help to contribute towards meeting identified need.

Transit provision can take the form of negotiated stopping or transit sites or a combination of both. The plan could include a London-wide target for transit pitches and provision for negotiated stopping arrangements. This could include consideration of the use of meanwhile sites.

We welcome evidence and experience of implementation to help inform this approach.

3. Growing London’s economy

London’s economy was worth almost £500bn in 2022, accounting for around 25 per cent of UK economic output. It has strengths in many different sectors including finance, professional services, sciences, innovation, tech, health, education, social care, hospitality, creative and green industries.

The government published its national Industrial Strategy which prioritises key growth-driving sectors for ambitious and targeted interventions to unlock growth. Many of these are important for London. The Mayor and London boroughs have published a London Growth Plan. It has a mission to grow the economy and increase productivity, improve the lives of all Londoners and drive green growth. It aims to support prosperity in London and across the UK. This highlights London’s key growth sectors:

- Financial, professional, and business services

- Creative industries

- Experience economy

- International education

- Life sciences

- Climate and Nature

Planning has a role to play to support the development of these growth sectors. This is alongside supporting housing delivery, identified in the London Growth Plan as a key constraint and priority. It includes unlocking infrastructure development and providing a range of premises across London. For example, offices, lab space, industrial and creative industries workspace, leisure outlets and shops. It also includes ensuring that land is available for critical infrastructure (such as energy) and other needs.

Like all economies across the globe, London’s economy was impacted by the pandemic. But it recovered strongly, returning to pre-pandemic annual output levels by 2024. There were 6.4 million workforce jobs in London at the last count and latest forecasts suggest employment could grow by around 800,000 jobs by 2050.

Economic activity in London takes place in a range of locations such as:

- the Central Activities Zone (including the Northern Isle of Dogs)

- specialist clusters of economic activity

- town centres and high streets

- industrial land.

The Central Activities Zone (CAZ) remains uniquely important to London and the country overall. However, London’s economy should also be supported by economic growth across its Opportunity Areas, town centres and industrial locations. This enables jobs, services, and business opportunities near to people’s homes.

In 2020, the government introduced a new planning use called Class E, which covers a range of commercial, business and service uses. These include shops, cafes and restaurants, indoor sport, health centres, nurseries, offices, research facilities and light industrial. Class E uses can change to any other use within this class without planning permission. This means business premises can adapt to changing circumstances and this flexibility can reduce the likelihood of commercial premises being left vacant. In some circumstances, these Use Class E uses can also be converted to housing without needing planning permission.

Although these changes were introduced before the current London Plan was finalised, it was too late to change it. This means that many of the policies in the current plan are based on the old use classes which were less flexible. A new policy approach is therefore needed, reflecting these national changes.

It is also noted that over one million square metres of building stock (equivalent to about nine Shards) do not meet upcoming energy requirements. These require about £350m of investment to upgrade them and about half of this space is at risk of becoming obsolete. It is vital to ensure this stock continues to contribute to London’s development capacity, either through upgrades or repurposing for other uses.

3.1 The Central Activities Zone

The Central Activities Zone (CAZ) is a defined area of central London which contains a unique concentration and mix of business, cultural, shopping and entertainment uses. It includes places like the West End, Oxford Street, the City of London, South Bank and Knightsbridge. Around a third of London’s jobs are within the CAZ. Together with the Northern Isle of Dogs, it generates more than 11 per cent of the UK’s economic output. These areas are also home to almost 300,000 residents.

It is important that the CAZ can continue to function and evolve and to recover from the pandemic. To improve its resilience, we need to safeguard and enhance the unique concentrations of employment, business, culture, and night-time uses in the CAZ. We must also ensure there is enough floorspace provided across the area to meet future demand for these uses. There are still many debates about the future of office working. However, there is high demand for high quality, well-connected commercial floorspace (primarily office) which is driving investment, renewal, and demand. It offers an unparalleled labour and visitor catchment area, underpinned by the very high public transport connectivity and capacity. Together, these are uniquely important for driving productivity and supporting world city functions.

The London Plan could identify key areas with high demand and concentrations of economic activity and further prioritise commercial development and CAZ functions there. One example is the new Mayoral Development Corporation to deliver a reinvigorated hub for leisure, culture, and retail in Oxford Street. There are also other locations such as the areas around key stations like Euston. It could include strengthening ‘agent of change’ protections for cultural and night-time economic uses to ensure their operation is not impacted by new residential development.

As set out in Section 2 above, we could also consider whether amendments should be made to the CAZ boundary. This could help to better reflect areas with the concentration and mix of uses that are unique to the CAZ. It would exclude areas that are predominantly residential in character.

Additionally, we could consider if centrally located affordable workspace should refocus on the types of uses critical to CAZ and the area’s success, including culture and hospitality. Affordable workspace is discussed in more detail below.

We welcome evidence and views about how we might best balance key objectives for CAZ and support its unique role and benefits to the economy.

3.2 Specialist clusters of economic activity

London contains various areas and clusters of economic activity. These include scientific, innovation and technology clusters such as the Knowledge Quarter, MedCity, Tech City and the Cancer hub. London has long been home to financial services clusters in the City, Canary Wharf and Central London (Westminster). There are creative and cultural clusters too, identified by the 12 Creative Enterprise Zones and the Thames Estuary Production Corridor. There are also night-time economy clusters such as the West End, Shoreditch, and Camden Town. Many of these activities were highlighted in the recently consulted national industrial strategy.

Many clusters are found in the Central Activities Zone. Others are covered by Opportunity Area, town centre or industrial designations, reflecting their role as key locations for economic activity. However, there are also clusters that don’t match well with existing designations. For example, the life sciences clusters emerging at White City and Whitechapel, or the East London Fashion District in and around Stratford.

The next plan could identify all clusters of economic activity beyond CAZ, recognising that some are not well-suited to a town centre or industrial designation. The approach could provide a new, flexible recognition of the range of locations that support London’s economy. Care would need to be taken to ensure that the approach did not deter investment from other sectors or result in stagnation.

This approach could also provide support for the development and evolution of new economic clusters in accessible locations. These new clusters could provide more jobs in varied locations in London. However, they may need investment, for example in transport and infrastructure, to enable them to fully develop.

We are seeking views about the value of these approaches, including any impact on other uses. We further welcome evidence and experience of implementation to help inform the approach.

3.3 Town centres and high streets

London has a network of over 240 town centres and more than 600 high streets, each performing different roles and functions. Over time, they have faced many challenges, but they have adapted, proved to be resilient and are valued by Londoners. Ninety per cent of Londoners live within a ten-minute walk of a town centre or high street.

In the next plan we want to continue to help ensure that high streets remain a central feature of London’s economic and civic life. This must support town centre locations to adapt to include a much wider range of businesses, jobs, and commercial activity. For example, light industrial, life sciences and laboratories, data centres, leisure, circular economy activity and last mile logistics. As highlighted in Section 2 above, housing will also play an important role in town centres. This is because it brings more footfall and demand for local shops and other local businesses and improves viability of services such as bus routes.

Responding to these challenges and changes to introduce Use Class E, the London Plan could take a very flexible approach to the range of businesses in town centres and high streets. This would explicitly enable any commercial and other appropriate development (such as places of worship, health and educational uses, nursing homes) in any strategic town centre (International to District town centres). It would be a significant change from the current plan. This sets out differences in the type and scale of development expected in different town centres and establishes a hierarchy that can be a barrier to development and investment. For example, it would remove the inference that office headquarters should only be in International town centres or that District town centres should not have offices in well-connected locations.

We welcome evidence and experience of implementation to help inform this approach.

If this approach was taken, some requirements and restrictions could still be put in place. These could include conditions on planning permission or planning legal agreements. Another example is where there are different use classes such as betting shops, pay day loan shops or hot food takeaways. Restrictions could also be put in place where new premises are re-provided in a development specifically to replace lost facilities, such as artists’ studios or maker space or social or community infrastructure. There may also be some town centre classifications that might be considered differently in future, such as those in CAZ.

The plan could also require the ground floor of buildings in key locations to be designed in a way that allowed more flexibility between uses such as shops, healthcare facilities or light industrial uses. It could also require active frontages in some town centre locations or designate some town centres areas as suitable for late night uses.

We are seeking views as to where the right balance lies and evidence and views about what the right approach might be.

The London Plan could also require boroughs to set out clear plans for key town centres to accommodate growth. This could include economic growth, transport networks and public realm, greening and resilience (from environmental risks such as flooding and heat risk), and areas suitable for 24-hour activity, light industrial, other business uses that don’t need high footfall, and for housing.

We welcome evidence and experience of implementation to help inform this approach.

The previous government made significant expansions to rights to convert business premises into homes without planning permission (using permitted development rights). The London Plan could be clearer about the circumstances when town centre boundaries are redefined to release poorly performing areas, and how housing can come forward in released areas and in designated town centres. This might incentivise more housing to come forward by planning permission, which is better quality and includes affordable housing. It might also prompt boroughs to apply to restrict permitted development rights if this is alongside a clear and positive route for housing delivery in town centres through planning permissions.

We are seeking views about where the right balance lies.

There are currently several high streets that are not designated, and the plan could require boroughs to review these areas. They could then either designate them as part of the town centre network or release them for other uses such as light industrial, social and community uses and new homes.

At the same time, there are parts of London, particularly in outer areas, that are poorly served by local shops and services. Some locations are also dominated by out-of-town retail parks which provide shopping but not a functional town centre. This increases car dependency and has a particular impact on older and disabled Londoners, expectant mothers, and families with children. For these groups, it can create barriers in accessing local shopping and services.

We will review town centre designations and welcome views about changes to existing town centre classifications or improvements in access to existing high streets. We also welcome views about where new town centres or local parades should be supported or required in areas that are currently deficient or where significant growth is planned.

We could also consider approaches to help reactivate high street properties if they are vacant for an extended time, including for meanwhile uses. This could provide more opportunities for affordable business and community space. It could also help high streets across the capital to remain vibrant, attractive, inclusive, and safe hubs for residents, workers, and visitors. Powers outside planning may also be relevant. Examples include new powers for high street rental auctions that give businesses and community groups a ‘right to rent’ long-neglected town-centre commercial properties.

We welcome evidence and views about what approaches might be used in the London Plan.

3.4 Industrial land

The capital cannot function without sufficient land to service residents, businesses, and visitors. However, London has lost 18 per cent of its industrial land between 2001 and 2020. Two thirds of the remaining industrial capacity is on designated industrial land, where less than 10 per cent is not in industrial use.