Key information

Publication type: The London Plan

Publication status: Adopted

Publication date:

Contents

9 sections

Policy G1 Green infrastructure

8.1.1 A green infrastructure approach recognises that the network of green and blue spaces,[133] street trees, green roofs and other major assets such as natural or semi-natural drainage features must be planned, designed and managed in an integrated way. Policy G1 sets out the strategic green infrastructure approach and provides a framework for how this can be assessed and planned for. The remaining policies in this chapter provide more detail on specific aspects of green infrastructure, which work alongside other policies in the Plan to achieve multiple objectives. Objectives include: promoting mental and physical health and wellbeing; adapting to the impacts of climate change and the urban heat-island effect; improving air and water quality; encouraging walking and cycling; supporting landscape and heritage conservation; learning about the environment; supporting food growing and conserving and enhancing biodiversity and ecological resilience alongside more traditional functions of green space such as play, sport and recreation.

8.1.2 All development takes place within a wider environment and green infrastructure should be an integral element and not an ‘add-on’. Its economic and social value should be recognised as highlighted in the London i-Tree Assessment[134] and the Natural Capital Account for London’s Public Parks.[135]

8.1.3 To help deliver on his manifesto commitment to make more than half of London green by 2050, the Mayor will review and update existing Supplementary Planning Guidance on the All London Green Grid – London’s strategic green infrastructure framework – to provide guidance on the strategic green infrastructure network and the preparation of green infrastructure strategies.

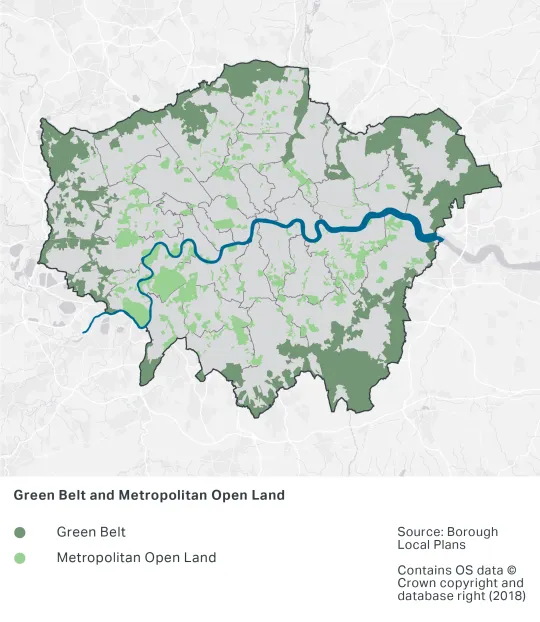

Policy G2 London’s Green Belt

8.2.1 The Mayor strongly supports the continued protection of London’s Green Belt. The NPPF provides a clear direction for the management of development within the Green Belt and sets out the processes and considerations for defining Green Belt boundaries. London’s Green Belt makes up 22 per cent of London’s land area and performs multiple beneficial functions for London, such as combating the urban heat island effect, growing food, and providing space for recreation. It also provides the vital function of containing the further expansion of built development. This has helped to drive the re-use and intensification of London’s previously developed brownfield land to ensure London makes efficient use of its land and infrastructure, and that inner urban areas benefit from regeneration and investment.

8.2.2 Openness and permanence are essential characteristics of the Green Belt, but, despite being open in character, some parts of the Green Belt do not provide significant benefits to Londoners as they have become derelict and unsightly. This is not, however, an acceptable reason to allow development to take place. These derelict sites may be making positive contributions to biodiversity, flood prevention, and climate resilience. The Mayor will work with boroughs and other strategic partners to enhance access to the Green Belt and to improve the quality of these areas in ways that are appropriate within the Green Belt.

Figure 8.1 - Green Belt and Metropolitan Open Land

Policy G3 Metropolitan Open Land

8.3.1 Metropolitan Open Land is strategic open land within the urban area. It plays an important role in London’s green infrastructure – the network of green spaces, features and places around and within urban areas. MOL protects and enhances the open environment and improves Londoners’ quality of life by providing localities which offer sporting and leisure use, heritage value, biodiversity, food growing, and health benefits through encouraging walking, running and other physical activity.

8.3.2 Metropolitan Open Land is afforded the same status and protection as Green Belt land. Any proposed changes to existing MOL boundaries must be accompanied by thorough evidence which demonstrates that there are exceptional circumstances consistent with the requirements of national policy.

8.3.3 Additional stretches of the River Thames should not be designated as Metropolitan Open Land, as this may restrict the use of the river for transport infrastructure related uses. In considering whether there are exceptional circumstances to change MOL boundaries alongside the Thames and other waterways, boroughs should have regard to Policy SI 14 Waterways – strategic role to Policy SI 17 Protecting and enhancing London’s waterways and the need for certain types of development to help maximise the multifunctional benefits of waterways including their role in transporting passengers and freight.

8.3.4 Proposals to enhance access to MOL and to improve poorer quality areas such that they provide a wider range of benefits for Londoners that are appropriate within MOL will be encouraged. Examples include improved public access for all, inclusive design, recreation facilities, habitat creation, landscaping improvement and flood storage.

Policy G4 Open space

8.4.1 Open spaces, particularly those planned, designed and managed as green infrastructure – provide a wide range of social, health and environmental benefits, and are a vital component of London’s infrastructure. All types of open space, regardless of their function, are valuable in their ability to connect Londoners to open spaces at the neighbourhood level. Connectivity across the network of open spaces is particularly important as this provides opportunities for walking and cycling. Green spaces are especially important for improving wildlife corridors.

8.4.2 Boroughs should undertake an open space needs assessment, which should be in-line with objectives in green infrastructure strategies (Policy G1 Green infrastructure) (drawing from existing strategies such as play, trees and playing pitches). These strategies and assessments should inform each other to deliver multiple benefits in recognition of the cross-borough function and benefits of some forms of green infrastructure. Assessments should take into account all types of open space, including open space that is not publicly accessible, to inform local plan policies and designations.

8.4.3 The creation of new open space, particularly green space, is essential in helping to meet the Mayor’s target of making more than 50 per cent of London green by 2050. New provision or improved public access should be particularly encouraged in areas of deficiency in access to public open space. It is important to secure appropriate management and maintenance of open spaces to ensure that a wide range of benefits can be secured and any conflicts between uses are minimised.

8.4.4 Proposals to enhance open spaces to provide a wider range of benefits for Londoners will be encouraged. Examples could include improved public access, inclusive design, recreation facilities, habitat creation, landscaping improvement or Sustainable Drainage Systems (SuDS).

Table 8.1 - Public open space categorisation

This table gives examples of typical open space typologies in London; other open space types may be included to reflect local circumstances

Policy G5 Urban greening

8.5.1 The inclusion of urban greening measures in new development will result in an increase in green cover, and should be integral to planning the layout and design of new buildings and developments. This should be considered from the beginning of the design process.

8.5.2 Urban greening covers a wide range of options including, but not limited to, street trees, green roofs, green walls, and rain gardens. It can help to meet other policy requirements and provide a range of benefits including amenity space, enhanced biodiversity, addressing the urban heat island effect, sustainable drainage and amenity – the latter being especially important in the most densely developed parts of the city where traditional green space is limited. The management and ongoing maintenance of green infrastructure should be considered and secured through the planning system where appropriate.

8.5.3 A number of cities have successfully adopted a ‘green space factor’ to encourage more and better urban greening. The Mayor has developed a generic Urban Greening Factor model to assist boroughs and developers in determining the appropriate provision of urban greening for new developments. This is based on a review of green space factors in other cities.[137] The factors outlined in Table 8.2 are a simplified measure of various benefits provided by soils, vegetation and water based on their potential for rainwater infiltration as a proxy to provide a range of benefits such as improved health, climate change adaption and biodiversity conservation.

8.5.4 The UGF is currently only applied to major applications, but may eventually be applied to applications below this threshold as boroughs develop their own models. London is a diverse city so it is appropriate that each borough develops its own approach in response to its local circumstances. However, the challenges of climate change, poor air quality and deficiencies in green space need to be tackled now, so while each borough develops its own bespoke approach the Mayor has recommended the standards set out above. Further guidance will be developed to support implementation of the Urban Greening Factor.

8.5.5 Residential development places greater demands on existing green infrastructure and, as such, a higher standard is justified. Commercial development includes a range of uses and a variety of development typologies where the approach to urban greening will vary. Whilst the target score of 0.3 does not apply to B2 and B8 uses, these uses will still be expected to set out what measures they have taken to achieve urban greening on-site and quantify what their UGF score is.

8.5.6 The Urban Greening Factor for a proposed development is calculated in the following way:

(Factor A x Area) + (Factor B x Area) + (Factor C x Area) etc. divided by Total Site Area.

So, for example, an office development with a 600 sq.m. footprint on a site of 1,000 sq.m. including a green roof, 250 sq.m. car parking, 100 sq.m. open water and 50 sq.m. of amenity grassland would score the following;

(0.7 x 600) + (0.0 x 250) + (1 x 100) + (0.4 x 50) / 1000 = 0.54

8.5.7 So, in this example, the proposed office development exceeds the interim target score of 0.3 for a predominately commercial development under Part B of Policy G5 Urban greening.

Table 8.2 - Urban Greening Factors

Notes for Table 8.2

A. Living roofs - Intensive green roofs

B. Trees in hard landscapes -Guide for delivery

F. RHS - Hedges

Policy G6 Biodiversity and access to nature

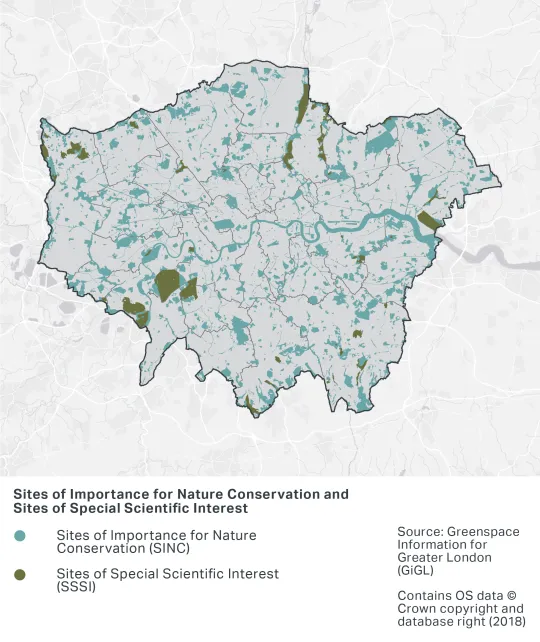

8.6.1 Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation (SINCs) comprise:

- Sites of Metropolitan Importance – strategically-important conservation sites for London

- Sites of Borough Importance – sites which support habitats or species of value at the borough level

- Sites of Local Importance – sites which are important for the provision of access to nature at the neighbourhood level.

Several Sites of Metropolitan Importance also have statutory European or national nature conservation designations (see paragraph 8.6.3)

8.6.2 The level of protection afforded to SINCS should be commensurate with their status and the contribution they make to wider ecological networks. When undertaking comprehensive reviews of SINCs across a borough, or when identifying or amending Sites of Metropolitan Importance, boroughs should consult the London Wildlife Sites Board.

8.6.3 Sites with a formal European or national designation (including Special Protection Areas, Special Areas of Conservation, Sites of Special Scientific Interest, National Nature Reserves and Local Reserves) are protected by legislation. There are legal provisions which ensure these sites are not harmed by development; there is a duty to consult Natural England on proposals that might affect these sites, and undertake an appropriate assessment of the potential impacts on European sites if a plan or project is likely to have a significant effect on the integrity of a European site.

8.6.4 Although heavily urbanised, London consists of a wide variety of important wildlife habitats, including a number of sites which have national and international protection. These habitats range from semi-natural features such as chalk grasslands and ancient woodlands to more urban habitats such as reservoirs and vegetated railway corridors. The wildlife value of these sites must be protected and appropriate maintenance regimes should be established to maintain or enhance the wildlife value of sites, recognising the additional pressure some sites may experience due to London’s projected growth. Improved sustainable access to wildlife sites should be secured, where appropriate, so that Londoners can better experience and appreciate the natural environment within the city. The connections between protected sites – green corridors – are often critical in helping to sustain wildlife populations that would be vulnerable if they were confined to isolated areas of habitat. London’s water spaces make up an important set of habitats in London. Policy SI 17 Protecting and enhancing London’s waterways addresses the protection of water spaces, with a particular priority for improving and restoring them. The habitat value of waterways is a key element of their future management.

8.6.5 Development proposals that are adjacent to or near SINCs or green corridors should consider the potential impact of indirect effects to the site, such as noise, shading or lighting. There may also be opportunities for new development to contribute to enhancing the nature conservation value of an adjacent SINC or green corridor by, for example, sympathetic landscaping that provides complementary habitat. The London Environment Strategy includes guidance on identifying SINCs (Appendix 5) as well as habitat creation targets and a comprehensive list of priority species and habitats that require particular consideration when planning decisions are made. The London Wildlife Sites Board offers help and guidance to boroughs on the selection of SINCs.[138]

Figure 8.2 - Designated nature conservation sites

8.6.6 Biodiversity net gain is an approach to development that leaves biodiversity in a better state than before. This means that where biodiversity is lost as a result of a development, the compensation provided should be of an overall greater biodiversity value than that which is lost. This approach does not change the fact that losses should be avoided, and biodiversity offsetting is the option of last resort. The Mayor will be producing guidance to set out how biodiversity net gain applies in London.

Policy G7 Trees and woodlands

8.7.1 Trees and woodlands play an important role within the urban environment. They help to trap air pollutants, add to amenity, provide shading, absorb rainwater and filter noise. They also provide extensive areas of habitat for wildlife, especially mature trees. The urban forest is an important element of London’s green infrastructure and comprises all the trees in the urban realm, in both public and private spaces, along linear routes and waterways, and in amenity areas. The Mayor and Forestry Commission have previously published a London Tree and Woodland Framework and Supplementary Planning Guidance on preparing tree strategies to help boroughs plan for the management of the urban forest.[141] These, and their successor documents, should inform policies and proposals in boroughs’ wider green infrastructure strategies.

8.7.2 The Mayor wants to increase tree canopy cover in London by 10 per cent by 2050. Green infrastructure strategies can be used to help boroughs identify locations where there are strategic opportunities for tree planting to maximise potential benefits. Trees should be designed into developments from the outset to maximise tree planting opportunities and optimise establishment and vigorous growth. When preparing more detailed planning guidance boroughs are also advised to refer to sources such as Right Trees for a Changing Climate[142] and guidance produced by the Trees and Design Action Group.[143]

8.7.3 An i-Tree Eco Assessment of London’s trees quantified the benefits and services provided by the capital’s urban forest.[144] This demonstrated that London’s existing trees and woodlands provide services (such as pollution removal, carbon storage, and storm water attenuation) valued at £133 million per year. The cost of replacing these services if the urban forest was lost was calculated at £6.12 billion. Consequently, when trees are removed the asset is degraded and the compensation required in terms of substitute planting to replace services lost should be based on a recognised tree valuation method such as CAVAT[145] or i-Tree Eco.[146]

Policy G8 Food growing

8.8.1 Providing land for food growing helps to support the creation of a healthier food environment. At the local scale, it can help promote more active lifestyles and better diets, and improve food security. Community food growing not only helps to improve social integration and community cohesion but can also contribute to improved mental and physical health and wellbeing.

8.8.2 As provision for small-scale food growing becomes harder to deliver, innovative solutions to its delivery should be considered, such as green roofs and walls, re-utilising existing under-used spaces and incorporating spaces for food growing in community schemes such as in schools. Where sites are made available for food growing on a temporary basis landowners/developers will need to be explicit over how long sites will be available to the community.

8.8.3 At a more macro scale, providing land for food growing helps to support farming and agriculture. Providing food closer to source helps to create a sustainable food network for the city, supports the local economy, and reduces the need to transport food, thereby reducing transport emissions and helping to address climate change. There are also longer-term biodiversity benefits, and farmers adopting agri-environmental stewardship schemes are more likely to deliver good environmental practice. For all food growing, consideration should be given to the historic use of the land and any potential contamination.

8.8.4 The Mayor’s Food Strategy prioritises the need to help all Londoners to be healthier and for the food system to have less of a negative environmental impact.

8.8.5 The Capital Growth network is London’s food growing network, which continues to promote community food growing across the capital, as well as delivering food-growing skills and employment opportunities for Londoners.

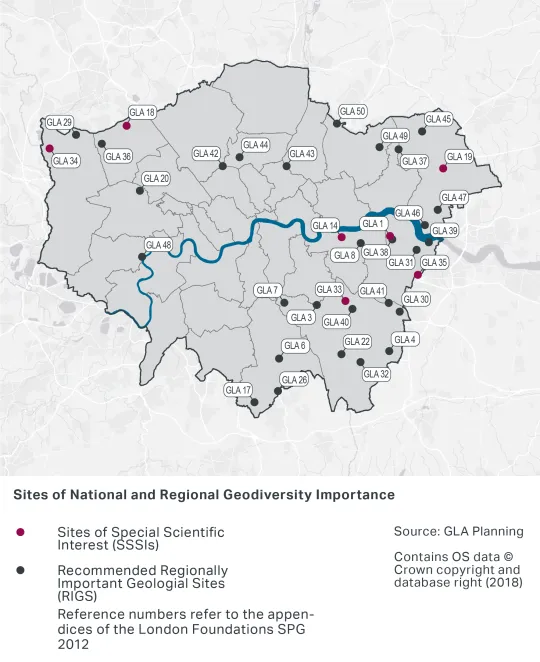

Policy G9 Geodiversity

8.9.1 Geodiversity is a fundamental cornerstone of our everyday lives. Geology affects where we build, how we construct buildings and how we deliver associated services. It influences the design and layout of infrastructure, filters our drinking water and underpins the landscape around us. Geodiversity cannot be replaced or recreated (other than on geological timescales).

8.9.2 London’s geodiversity sites are shown in Figure 8.3. Geodiversity sites with existing or proposed European or national designations are Sites of Special Scientific Interest and subject to statutory protection. Boroughs should protect and enhance RIGSs and LIGSs through their Development Plans. The Mayor will continue to work with the London Geodiversity Partnership to promote geodiversity and will prepare updated Supplementary Planning Guidance as necessary.

8.9.3 Geodiversity sites should be recognised for their importance in providing habitats for biodiversity and in allowing delivery of ecosystem services.

8.9.4 Where appropriate, access should be provided to geodiversity sites, although it is recognised that this is not always desirable. Geological sites will require appropriate maintenance regimes to ensure that these assets are properly protected and managed.

Figure 8.3 - Geodiversity sites

[133] London’s waterways and their multifunctional role are specifically addressed in Policy SI 14 Waterways – strategic role to Policy SI 17 Protecting and enhancing London’s waterways.

[134] Valuing London's Urban Forest - Results of the London i-Tree Eco Project, Treeconomics, 2015, https://www.london.gov.uk/WHAT-WE-DO/environment/environment-publications/valuing-londons-urban-forest

[135] Natural capital accounts for public green space in London, Vivid Economics, 2017, https://www.london.gov.uk/what-we-do/environment/parks-green-spaces-and-biodiversity/green-infrastructure/natural-capital-account-london?source=vanityurl

[136] Areas of Deficiency in Access to Public Open Space, GiGL, https://www.gigl.org.uk/open-spaces/areas-of-deficiency-in-access-to-public-open-space/?highlight=open%20space%20deficiency

[137] Urban Greening Factor for London, The Ecology Consultancy, 2017, https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/urban_greening_factor_for_london_final_report.pdf

[138] Tree and Woodland Strategy Guidance, Mayor of London, 2013, [https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/sinc_selection_process_2019_update_.pdf]

[139] Forestry Commission/Natural England (2018): Ancient woodland and veteran trees; protecting them from development, https://www.gov.uk/guidance/planning-applications-affecting-trees-and-woodland

[140] Category A, B and lesser category trees where these are considered by the local planning authority to be of importance to amenity and biodiversity, as defined by BS 5837:2012

[141] Tree and Woodland Strategy Guidance, Mayor of London, 2013, https://www.london.gov.uk/what-we-do/planning/implementing-london-plan/london-plan-guidance-and-spgs/tree-and-woodland

[142] The Right Trees for Changing Climate Database, http://www.righttrees4cc.org.uk/

[143] Trees and Design Action Group guidance, http://www.tdag.org.uk/guides--resources.html

[144] Valuing London's Urban Forest - Results of the London i-Tree Eco Project, Treeconomics, 2015, https://www.london.gov.uk/WHAT-WE-DO/environment/environment-publications/valuing-londons-urban-forest

[146] i-Tree Eco, https://www.itreetools.org/