Key information

Publication type: General

Contents

7 sections

1. Introduction: Why is this research important?

The people and organisations that run community-led and cultural spaces play a fundamental role in creating cultural, social and economic value for Londoners. Community-led and cultural spaces serve London’s diverse communities. They contribute positively to community cohesion and wellbeing, and provide opportunities for Londoners to represent their unique identities, and celebrate shared experiences.

The ability of all Londoners to access spaces representing their communities is key to their agency in telling London’s history, and shaping its future. These spaces are run by:

- charities

- community interest companies

- social enterprises

- independent businesses

- other types of organisations.

Community-led and cultural spaces are critical to realising the Mayor of London’s vision for good growth. Good growth means regeneration that is inclusive, protects London’s character and strengthens community cohesion and social integration. Evidence shows that when local groups are formally involved in the design, development, governance, management and importantly ownership of spaces, it can increase social capital and wellbeing in a community.Reference:1Protecting and growing the city’s cultural and social infrastructure is a cross-cutting priority across the Mayor’s policies (see Appendix 1).

Worryingly, over the past decade and a half, London’s community-led and cultural spaces have faced increasing risks. High land values, business rates, redevelopment pressures, funding reductions, the COVID-19 pandemic, and most recently, the cost-of-living crisis have challenged even the best-established spaces.

Since 2016, the Mayor’s Culture and Community Spaces at Risk programme has been providing information, advice, guidance, advocacy and policy work to help protect against threats to London’s community-led and cultural spaces. It has also been directly supporting organisations working to save spaces at risk. This involves collaborating with community-led and cultural organisations, local authorities, other public-sector bodies, businesses, sector partners and funders.

Evidence from direct engagement with organisations operating spaces indicates that spaces run by and serving Londoners who are more likely to face inequalities are at particular risk. This is because the operators of these spaces face additional challenges when interacting with the planning, licensing, funding, or property systems. While the Mayor's Culture and Community Spaces at Risk programme can support spaces at immediate risk, system change is needed to address the root causes. We commissioned research to understand the disparities that organisations led by underrepresented groups face in their ability to secure and sustain spaces for cultural and community uses.

This report is not an exhaustive review of all barriers to securing and sustaining spaces in London. Rather, it is a catalyst for change. The case studies featured in the report provide both inspiration and a call to action for stakeholders in central government, local authorities, funders, the GLA group, and other public-sector organisations to help reduce and ultimately remove the barriers.

2. Methodology: Co-created research

About this report

This report draws on research commissioned by the CCSaR programme.

An internal scoping study, exploring barriers in the planning system for community-led and cultural spaces, formed the basis of this report.

The Ubele Initiative and Locality developed an evidence base to:

- identify barriers to securing and sustaining community-led and cultural spaces, faced by underrepresented groups

- collect case study evidence.

The process drew on the lived experience and expertise of community-led and cultural organisations as active research participants, rather than passive subjects of the research.

The Ubele Initiative is an African diaspora-led, voluntary-sector infrastructure and delivery organisation. It acts as a catalyst for social and economic change, and aims to empower Black and racially minoritised communities in the UK, by supporting the growth of community-based organisations.

Locality is a national membership network supporting local community organisations through specialist advice, peer-learning, resources and campaigns.

The evidence base

This report draws on a diverse evidence base that includes:

- a literature review

- written summaries of 20 in-depth interviews of leaders from community-led and cultural spaces

- interviews with local authority officers

- a review of over 70 cases from the CCSaR programme between 2020 and 2021.

The Ubele Initiative and Locality established two steering groups to set out a research framework for developing the evidence base. One included leaders from London-based community-led and cultural organisations. The second included representatives from relevant policy organisations.

Each steering group held two meetings. The first meeting, at the outset, reviewed the initial themes and research framework. The second meeting, at the end of the evidence collection, evaluated findings and ideas for recommendations.

We have shared this final report, which brings the research together, with the steering groups for their review.

Terminology

This section provides definitions for the terminology used in this report. The report seeks to strike a balance between naming groups that are disproportionately impacted by inequalities, and avoiding generalisations about groups of Londoners.

Where the report draws on outside evidence or case studies, it uses the terms those authors use. We acknowledge that Londoners’ identities are as diverse as the city itself, and that attitudes towards the terms used in this report may evolve.

Underrepresented groups

Groups of people that face inequalities because they are not represented in political, business and/or financial leadership, or in public-sector decision-making.

Marginalisation

A situation that occurs where social systems act to exclude groups of people from resources, representation and/or participation.

Community

A group of people who share an interest or identity. This could mean living in a certain area, sharing an ethnic, national or religious background or being part of an organisation. It could also mean people who frequently visit a space, such as a pub, community centre or local shop. Communities are not uniform but are internally diverse. People may also belong to many different communities.

Protected characteristics

The nine characteristics currently protected by equality legislation. It is illegal to discriminate against someone based on their age, disability, sex, gender reassignment, ethnicity, pregnancy and maternity, religion and / or belief, marital status, or sexual orientation.Reference:2

This report calls for decision-makers to go above and beyond the recognition of protected characteristics, and recognise other inequalities that impact on Londoners – such as socioeconomic status.

Equality

Equality is about recognising and respecting differences, including diverse needs. This means everyone can live their lives free from discrimination, knows their rights will be protected and has a chance to succeed in life.Reference:3

Equity

Equity is about addressing the barriers that cause unequal outcomes between people. In an equitable situation, everyone has the resources they need to reach an equal outcome. This means taking action to help groups facing inequalities access the resources they need to overcome them.

An example of an equal but not equitable situation is where three organisations can bid for a building, but only one already has enough money to buy it.

Spaces included in the scope of this research

Community-led and cultural spaces are places for community organising, giving voice to communities and celebrating their cultures. The people and organisations that run them bring spaces to life with different activities.

Spaces enable organisations to:

-

provide services and bring communities together

-

earn income, and generate and retain wealth

-

reinvest in the services and activities they know their communities need.

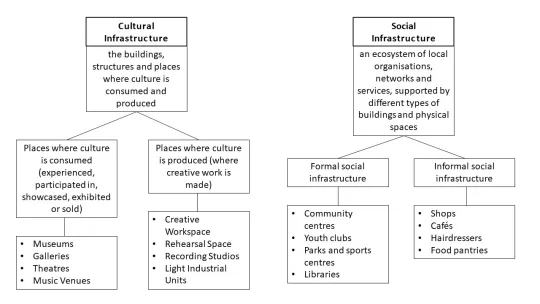

The Mayor’s policies describe community-led and cultural spaces as 'cultural infrastructure' or 'social infrastructure'. These categories exist to help policymakers understand the role that specific spaces play for different communities, and the organisations that run the spaces. However, across London, spaces may blur the boundaries between these definitions, and are hard to categorise in this way.

Cultural infrastructure: the buildings, structures and places where culture is consumed and produced

- Places where culture is consumed (experienced, participated in, showcased, exhibited or sold):

- Museums

- Galleries

- Theatres

- Music Venues

- Places where culture is produced (where creative work is made):

- Creative workspace

- Rehearsal space

- Recording studios

- Light industrial units

Social infrastructure: an ecosystem of local organisations, networks and services, supported by different types of buildings and physical spaces

- Formal social infrastructure:

- Community centre

- Youth club

- Parks and sports centres

- Libraries

- Informal social infrastructure:

- Shops

- Cafes

- Hairdressers

- Food pantries

For example, a music venue, theatre, or artists’ studio could offer training and skills-development opportunities, as well as opportunities to meet, create, and socialise.

A local restaurant could be a place where people go to find out about support services available in their native language. In some neighbourhoods, a café, a barber, or a tailor’s shop might hold significant cultural heritage value.

Locality, the national membership organisation for community organisations, found that their members provide 13 different services on average – including mental health support, employment advice, and health and social care.

Identifying spaces that hold cultural and community value is important in protecting them. Traditionally, heritage designation has focused on the physical qualities of spaces. However, evidence shows that communities also find other factors important to define what heritage is.

These factors include the use of a space, and what associations and meanings it has for people and communities.Reference:4

One of the four conservation values recognised by Historic England is communal value - what a place means to people and the relationship of a place to people’s collective experience. This includes the ways people draw their identity from their relationships with spaces.

Historic England recognises that heritage is linked to the specific communities that value a space, and the events associated with it.Reference:5

The Mayor’s Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Strategy states:

“London has a world-class cultural offer, but more needs to be done to help low-income groups, older people, disabled people and Black, Asian and minority ethnic groups to make the most of it. The cultural heritage of specific groups, for instance LGBTQ+ communities, also needs to be protected.”Reference:6

In neighbourhoods across London, communities have campaigned to protect spaces and places representing their communities’ unique cultural heritage. Examples of campaigns include:

- Bangladeshi-owned restaurants on Brick Lane in Tower Hamlets

- Black-owned bookseller and publisher in Finsbury Park

- LGBTQ+ pubs in Hackney.

More work must be done to identify and protect spaces that hold the rich histories of London’s diverse communities.

3. Context: Structural inequalities

London has high levels of inequality, impacting Londoners’ social and economic circumstances. Inequality affects Londoners’ income, employment, access to capital, wealth, housing and health.Reference:7 Reference:8 Reference:9

Race and ethnicity, gender, income level and class, disability, religion or belief, age, sexual orientation, gender identity, and other identity factors, impact how Londoners experience inequality.

London’s inequality is also intersectional. This means that a person identifying as part of two or more underrepresented groups – for example, someone who is from a Black, Asian or minority ethnic background, and who is also disabled – is more likely to face multiple kinds of disadvantage.Reference:10

Community-led and cultural spaces that provide opportunities to Londoners at the intersection of these disadvantages hold unique value. This is particularly true when these services are not available within mainstream provision.

For example, the London-based charity Sistah Space supports African and Caribbean-heritage women affected by domestic abuse. It also advocates to improve cultural awareness for Black women’s experiences in the wider violence against women and girls’ sector.

London’s inequalities are structural. This means they arise from historical situations and are deeply rooted in institutional systems that govern key factors in securing and sustaining cultural and community spaces – such as property ownership and finance.Reference:11

For example, previous government research found that Black African, Black Caribbean, Bangladeshi and Pakistani business loan applicants are more likely to have their applications rejected than Indian or White applicants.Reference:12

This disparity also impacts on the long-term sustainability of organisations. For example, 67 per cent of White business owners run established firms over 42 months old, compared to 43 per cent of Black business owners.Reference:13

Historic factors increase the challenges in accessing, securing and sustaining space. In 2019 it was widely reported that less than 1 per cent of England’s population own about half of the country’s land.Reference:14

Groups that historically have had less access to wealth creation and financial resources are less able to secure property in London, where land values are high. They are also more likely to lose access to property.

For example, between 2006 and 2016, London lost 56 per cent of its LGBTQ+ nightlife venues. In that period, the already-small number of venues specifically serving LGBTQ+ trans people, women and/or Black, Asian and minority ethnic Londoners were disproportionately affected by closures.Reference:15

A survey commissioned by the Mayor in spring 2022 found that, among spaces led by Londoners who identify as LGBTQ+, or as members of an ethnic minority, only 39 per cent are confident about operating in London in five years.Reference:16 Among organisations led by neither group, this rose to 57 per cent.

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and cost-of-living crisis

The COVID-19 pandemic emphasised the importance of grassroots, diverse-ledReference:17 organisations to London’s resilience. These organisations provide a range of services to their communities. They include:

- health and wellbeing support

- employment and entrepreneurship support

- legal advice

- workspaces

- cultural and educational activities.

Community-led and cultural spaces are strong indicators of communities’ overall resilience. Research found that areas with stronger community infrastructure saw higher rates of mutual aid and better wellbeing during the pandemic.Reference:18

During the pandemic, many organisations pivoted to deliver emergency support services, based on specialised knowledge of their communities’ needs.Reference:19 This was a crucial intervention as Londoners from underrepresented backgrounds faced disproportionate impacts from the pandemic. They experienced higher infection and death rates, greater increases in unemployment and higher levels of mental ill health.Reference:20 Reference:21 Reference:22

However, the pandemic has also revealed the vulnerability of these organisations and their spaces. Many lost key sources of income, from performance ticket sales to space hire.

Other spaces that were already experiencing financial precarity faced crisis. In early 2020, The Ubele Initiative reported that 87 per cent of Black, Asian and minority ethnic-led organisations could cease operation by early July, due to having few or no reserves.Reference:23

Research also found that, nationwide, two-thirds of Black, Asian and minority ethnic-owned businesses had been unable to access government support funding.Reference:24

Organisations disproportionately impacted by the pandemic have also been struggling to endure the cost-of-living crisis. According to the cultural spaces survey conducted in summer 2022, 71 per cent of spaces led by Londoners from a Black, Asian or minority ethnic background, and 69 per cent of spaces led by LGBTQ+ Londoners, report being in a worse financial situation after the pandemic.Reference:25

A survey of 84 community-led and cultural organisations, conducted by the CCSaR programme in autumn 2022, found that in the cost-of-living crisis, organisations led by and serving minority ethnicities, children and young people, or low-income groups are twice as likely to be at risk of closure within three months, without further energy-bills relief.

The crisis is particularly impacting smaller organisations with less turnover. Thirty organisations with less than £500k turnover (around half of those surveyed) said they were likely to close within a year, without support.

4. Rebalancing power: Removing barriers to property and space

The risks that London’s community-led and cultural spaces face overall are well documented. The evidence base for this report shows how discrimination and structural inequalities create conditions of risk for spaces led by underrepresented groups.

The report identifies barriers to achieving equity in access to space. Imbalance of power is a common theme in these barriers. This imbalance exists in the processes that affect London’s community-led and cultural spaces – for example planning, land and property ownership, and funding decisions.

Overcoming these barriers requires all stakeholders to consider how they can shift power to the operators and users of space. This shift should mean involving communities as partners when shaping plans and making decisions that affect their assets.

The recommendations in this report will guide stakeholders – such as local authorities, other public-sector bodies and funders – to meaningfully shift power to communities. The call to action focuses on strategic, operational and tactical interventions that stakeholders can undertake, while encouraging broader structural change. The recommendations are supported by case studies showcasing best practice in addressing barriers identified in the report. The recommendations also include specific actions for the GLA group to take forward.

Understanding the barriers faced by underrepresented groups in securing and sustaining spaces for cultural and community uses is a vital first step in making tangible change happen. We invite local authorities, other public-sector bodies and funders to consider the report findings and recommendations, to help achieve equity in access to space and to deliver good growth.

The Good Growth by Design: Connective Social Infrastructure report identifies ways that restrictive funding and barriers to public engagement harm London’s social infrastructure ecosystem.

The Mayor’s Cultural Infrastructure Plan identifies five 'underlying conditions' that threaten spaces’ survival:

- land value increases

- the national planning system

- business rate increases

- licensing restrictions

- funding reductions.

The sections below explore each underlying condition in the Cultural Infrastructure Plan. Plus one more condition around networks and relationships, from the perspective of community-led and cultural spaces.

Drawing on the extensive evidence base, it highlights key barriers that intensify the risks to spaces led by and serving underrepresented groups. These barriers are linked to London’s structural inequalities. This section shows how they impact on underrepresented groups’ ability to secure and sustain space in London.

4.1 Underlying condition: Land value and increases in business rates

London’s high land values pose one of the biggest challenges facing all community-led and cultural spaces in London. They create a property market with high barriers to entry for renting and owning property, and put existing spaces at risk due to unsustainable rents.

Community-led and cultural spaces with business functions see their viability threatened as rents become increasingly difficult to sustain. Charities that rely on grant funding must devote more and more of their resources to paying their rent, reducing the resource available to deliver their services. Owning assets protects organisations from rising rents, redevelopment pressures and property-owner management decisions. However, organisations wishing to purchase assets face an enormous barrier to entry, and often lack access to legal and property expertise required to navigate the process.

High land values also make it harder for community-led and cultural organisations to compete in the property market against more lucrative land uses – such as housing or commercial office space. With fewer properties available for cultural and community uses, organisations face severe challenges finding affordable spaces that meet their needs. Even when they find premises, organisations report increasing difficulty agreeing long-term secure leases. Many property owners, including local authorities, are unwilling to sign long-term leases with cultural and community organisations.

High land values also impact spaces’ relationships with their property owners. They have made London property attractive to high-net-worth investors – some of whom are based overseas. For example, in 2016 the Guardian identified a 9 per cent yearly increase in London properties owned by offshore companies.Reference:26 Tenants increasingly report difficulty engaging with property owners where they are based overseas, or have complex ownership structures. They face difficulty communicating and negotiating with their property owners. This is a particular risk during crisis periods (for example during the pandemic), when a fast and flexible response is needed.

Property owners based outside London also might hold less localised knowledge about the organisation they are renting to. They may not be aware of the services the space provides to London’s communities, or its place in the local economy. This increases risks to organisations if property owners perceive them as liabilities, instead of valuable contributors to local social and economic wellbeing.

Finally, high land values increase costs to spaces by causing increased business rates. Business rates are set based on property values – meaning that London’s spaces can face significant increases whenever rates are re-evaluated. Many community-led and cultural organisations operate with narrow profit margins, and have limited ability to support sudden cost increases. Also, there are limited options to respond locally to barriers created by business rates, as the rates are set nationally.

What organisations have told us about their experience

- A dance company aiming to heighten the profile of Black dance and dancers in the UK acts as a lead tenant and steward of a multi-purpose community centre. The organisation has a tenancy-at-will arrangement with the property owner, which affords less security than a full lease. For example, either party can end the arrangement at any time. This lack of security has an adverse impact on the organisation’s ability to plan, access long-term funding and manage the building’s upkeep.

-

A centre supporting young LGBTQ+ Londoners has had to relocate multiple times. Every new move required time and resources to make the space feel safe, comfortable and accessible. Space is synonymous with safety – more so for communities facing continuous marginalisation and discrimination. The lack of secure, owned space affects the organisation’s ability to focus on the long-term, strategic development of services.

- A community-led organisation set up to improve local amenities, promote recreation and support local people’s health and wellbeing manages an adventure playground in a dense inner London area, where development pressure is high. The organisation has ambitious plans to invest in the adventure playground, and has identified potential funding sources. Investing in the site’ infrastructure will also improve the organisation’s sustainability and revenue position. The current lease is too short to secure major grants, and negotiations with the property owner have progressed slowly.

- Across the capital, there is demand for services to support young people in achieving their best potential. A small west London organisation provides a range of services for marginalised young people from Somali and Asian backgrounds. Services are run from a temporary building on a five-year lease. The building needs investment, but funders generally require longer leases before they will invest. This limits the organisation in planning for the future and increasing its services to support young people.

- An organisation providing counselling services for the LGBTQ+ community – including mental health support, youth mentoring and domestic/sexual violence support – has been based in its current premises for over 20 years. The organisation is in a tenancy-at-will arrangement, which limits the security of its tenure in a market where commercial property values have risen. The organisation’s long-term vision is to operate an intergenerational community centre that provides support for LGBTQ+ people and their family and friends. The organisation has outgrown its current space. It is struggling to find another that meets the needs of service users, is affordable and is in a safe and accessible location. Being on a tenancy at will may limit the financial options, in terms of access to finance or funding opportunities to secure better premises.

- Local authorities across London are under financial pressure and are reviewing their property portfolios. A south London-based community organisation has been delivering after-school provision for local children since 1985. The organisation is in a property owned by the local authority and has been trying to secure a long-term lease for several years. This process has been delayed by a lengthy community premises review, which has put all negotiations on hold.

Barriers increasing this risk

- Discrimination in access to credit impacts the ability of groups from Black, Asian and minority ethnic backgrounds to secure spaces.

- These groups face negative perceptions in terms of their ability to pay rent, and of the audiences/groups that they serve.

- Organisations serving London-wide populations, such as LGBTQ+ venues, needing a central and accessible space, but those spaces being the most expensive.

- Underrepresented groups have limited access to professional legal and property expertise needed to secure favourable heads of terms on long-term leases, often placing them in insecure tenancy agreements.

- Having short-term, insecure leases limits organisations’ eligibility to apply for core funding and the ability to plan.

Good practice

Securing historic cultural space through a Community Asset Transfer Reference:27

198 Contemporary Arts and Learning is an exhibition space in Brixton founded in 1988, after the Brixton riots. It is in an area formerly known as the Frontline. Following the 1981 Scarman Report, funding for regeneration came into the area through Brixton City Challenge, particularly for spaces serving the Black community. 198 Contemporary Arts and Learning is especially important because it's an incubator of emerging talent from Black artists, curators and arts educators. The organisation was renting its premises from Lambeth Council for 27 years before completing an asset transfer for the freehold in 2015, under the council’s Community Asset Transfer programme.

Read case study: Securing historic cultural space through a Community Asset Transfer

Recommendations

- Public-sector bodies, including the GLA group, can ensure that Community Asset Transfer policies are underpinned by support and guidance for community-led and cultural organisations to successfully conduct the process.

- Local authorities, the GLA group and other public-sector bodies can – when acting as property owners – seek to offer secure, long-term leases to community-led and cultural organisations, considering social value, equity, and long-term sustainability and income-generation capacity. In doing so they can be mindful of, and address, historic inequalities in securing space faced by underrepresented groups.

- Local authorities, the GLA group and other public sector bodies can adopt the highest quality co-production methods in the development of asset strategies and redevelopment proposals for their own property portfolios.

- Trusts and foundations can introduce funding streams that allow organisations led by underrepresented groups to access the legal and property expertise often required to apply for larger grants.

4.2 Underlying condition: National planning system

National planning policy shapes planning and development conditions for community-led and cultural spaces. The current National Planning Policy Framework lacks specific protections for cultural and social infrastructure. Also, permitted development rights within this framework put community-led and cultural assets at risk. They allow landowners and developers to convert many types of commercial property to housing without planning permission. This means assets within those properties can easily be lost. Restaurant, pub and shop assets are vulnerable to conversion – as are offices, and artists’ and creative workspaces.

Viability assessment requirements in the current Framework also affect the delivery and protection of community-led and cultural spaces. This is a process of assessing whether the development value of a site, weighed against the development costs, makes it financially viable for developers. Development proposals will only go forward if they provide commercial returns to landowners and developers. Many local authorities rely on contributions from developers to fund and provide cultural and social infrastructure.

However, developers can reduce liability for contributions through viability assessments demonstrating that development would be hindered by developer contributions, including those towards cultural or social infrastructure. This is a particular risk in lower-income neighbourhoods, where developers can argue that lower land values mean lower financial returns. Planning policy guidance suggests that developer profit of 15 to 20 per cent should be applied in viability assessments. This makes it more difficult for local authorities to negotiate planning obligations requiring developers to pay for cultural and social infrastructure.Reference:28 There is also a risk that unsuitable or inappropriate space is secured within new development. Spaces that are unsuitable for community or cultural use then remain empty, and are later converted to other uses.

The current National Planning Policy Framework also requires local authorities to achieve significant housing delivery. Council funding is limited, so local authorities rely on private housing development to meet these targets. This can create risks for community-led and cultural spaces through increased development pressure. There is a risk that planning authorities will approve development schemes that displace valued local assets if they determine that new housing delivery outweighs the importance of protecting the assets. This is a particular risk if there are gaps in policies protecting community-led and cultural spaces.

The London Plan sets a strong strategic framework for the protection and development of cultural and social infrastructure, and provides guidance for local development plans. Local Plans determine how planning decisions are taken forward. They can set out how to prioritise existing community-led and cultural spaces when development schemes might put them at risk.

However, the inclusion of Local Plan policies for protecting social and cultural infrastructure varies across boroughs. Most Local Plans include policies for delivering community spaces, but less than a third link community space provision to addressing inequalities.Reference:29 One example of a Local Plan linking community space to social inclusion is Kingston’s Core Strategy. This includes a specific policy requirement to protect and expand community facility provision in deprived areas.

The way the planning system assesses value also impacts how it protects community-led and cultural spaces. It often relies on quantitative measures, such as:

- number of housing units

- square footage of workspace

- jobs created

- investment attracted.

However, across London, there is no consistent definition of social value applied in the planning system.

Also, it is difficult for communities to engage in planning processes, from developing Local Plans to consulting on individual development schemes. The processes are lengthy and technical, and require long-term engagement. Property developers are much better placed to advance their goals through the planning system, due to the expertise, time and financial resource they can invest in it.

What organisations have told us about their experience

- A group of diverse-led independent businesses has been concerned about a new development’s impact on rent and business rates, at a time when local independent businesses are particularly vulnerable and face financial hardship. Despite local business owners and residents contributing to the initial plans for the area, and building the area’s reputation as a place for tourists and workers to visit, they feel that they have not been fully consulted on subsequent planning decisions that have impacted the neighbourhood. They are concerned that the changes to the area may lead to rising rents and displacement of the existing business community.

- A youth and community organisation serving at-risk young people and residents is based in a purpose-built youth centre. The organisation was originally founded by Londoners of South Asian heritage, creating safe spaces for young people experiencing racism in other settings. The organisation relies on income from private hire to fund the building’s annual rent and the services it provides. It has plans to redesign certain areas to create space for additional income generation but is unsure about how to navigate the planning system, and reduce risks and costs associated with securing the required permissions.

Barriers increasing this risk

- According to analysis undertaken in 2019 by the Town and Country Planning Association, Camden was the only London borough whose Local Plan included specific protections for community spaces supporting groups with protected characteristics.Reference:30

- Spaces valued by underrepresented groups are often unknown to local authorities, and so may not be represented in the Local Plan. They may also lack institutional recognition for the specific value they provide to certain communities. In some cases, this may be because the community functions of cultural heritage spaces (such as shops and salons) may not be visible to those who don’t visit those spaces. Another possible reason is that organisations providing arts, cultural or community activities on a small scale, or at grassroots level, may go under the radar of larger institutions. If the workforce of a local authority does not reflect the communities it serves, this risk may increase.

- Many community-led and cultural organisations lack the capacity, time and resource to navigate the planning system, prepare representations and campaign to save spaces that are at risk from redevelopment.

- Organisations led by speakers of English as a second language find it harder to engage effectively with the planning system.Reference:31

- Many areas of London have seen the emergence of neighbourhood forums following the 2011 Localism Act. Neighbourhood planning gives communities direct power to develop a shared vision for their neighbourhood, and shape the development and growth of their local area. However, 2019 research by Neighbourhood Planners London and Publica found that neighbourhood forums in areas of London with high socio-economic deprivation can face additional challenges in developing neighbourhood plans. These include a lack of funds and costs, a lack of skills, and limited engagement and membership.Reference:32

- Even if a Local Plan requires cultural and community premises to be re-provided through redevelopment, groups with less financial resource often cannot afford the increased rental value of the new spaces.

Good practice

Assessing the equalities impacts of development to protect cultural and community spaces

The London Borough of Tower Hamlets has strengthened the way it considers the Public Sector Equality Duty (PSED) in the planning process.

The PSED requires public authorities to have due regard to the objectives set out in section 149 of the Equality Act 2010. This means they must consider the needs set in the objectives when making decisions or delivering services. The objectives are to eliminate discrimination, advance equality of opportunity and foster good relations. The PSED applies when local authorities assess planning applications and make decisions about them.

The way local planning authorities do this varies greatly. The strengthened approach in Tower Hamlets makes it easier to consider how the potential loss of community and cultural spaces may impact different groups of people.

Co-produced community facilities redevelopment

The Selby Trust manages the Selby Centre, a major multi-purpose community centre at the heart of Tottenham. The Selby Centre brings together a rich mix of individuals and organisations, primarily from racialised and other historically-excluded communities in Haringey, Enfield and beyond.

The building the centre uses is reaching the end of its useful life. At the same time, there is increasing pressure on land due to the housing shortage. Selby Trust runs the centre partnered with Haringey Council as freeholder, with investment allowing centre redevelopment.

The plans were co-produced with Selby Trust and the communities that use it. They include new housing, alongside a replacement community centre with sports hall, community hall and outdoor sporting facilities.

Read case study: Co-produced community facilities redevelopment

Protecting cultural and community facilities through planning policies

Environmental charity Fourth Reserve Foundation looks after, and campaigns to preserve, sites along the green railway corridor between Honor Oak Park and Brockley stations. It wishes to bring Gorne Wood into public open-space use. Gorne Wood has been owned by a housing developer for 20 years.

Fourth Reserve Foundation engaged with the planning process to achieve its long-term goal of acquiring the site for public access. The organisation successfully applied for the site to be designated as an ancient woodland by Natural England; and as an asset of community value, a Locally Important Geological Site and a Metropolitan Site of Importance for Nature Conservation by Lewisham Council.

The designation as Metropolitan Open Land is included in Lewisham’s draft Local Plan. The planning designations mean that residential development on the Gorne Wood site is not permitted. The organisation is working with Lewisham Council to acquire the land through compulsory purchase for wildlife protection & woodland conservation.

Read case study: Protecting cultural and community facilities through planning policies

Recommendations

-

Local planning authorities can include, in their Local Plans, specific protections for community-led and cultural spaces led by or serving underrepresented groups. As an example, the Camden Local Plan states: “The Council will … ensure existing community facilities are retained recognising their benefit to the community, including protected groups.”Reference:33

-

Local planning authorities can ensure that infrastructure mapping and delivery planning includes community-led and cultural spaces led by and serving underrepresented groups.Reference:34

-

Local planning authorities can employ co-designed and participatory research methods, working with underrepresented groups to identify community-led and cultural spaces that serve these groups.

-

Local planning authorities can develop specific targets and actions for actively involving underrepresented groups when developing planning policy.

-

Local planning authorities can consider Article 4 Directions to remove permitted development rights that place community-led and cultural spaces at risk, recognising that community-led and cultural spaces may occupy properties with different use classes.

-

Central government can consider developing guidance on cultural and community infrastructure mapping and planning.

4.3 Underlying condition: Licensing restrictions

Licensed venues have come under increased pressure in the past decade due to new residential development in mixed-use areas of London. Development has brought more residents near licensed premises. Because of this, spaces such as music venues, nightclubs and other entertainment premises have come under scrutiny for drawing late-night crowds and noise.

Licensing controls over these activities have become stricter. Restrictive licensing conditions can have a negative impact on the sustainability of late-night venues. For example, limiting a nightclub’s opening hours can make the space unviable if it cannot make enough money from drink sales during these hours. A music venue may also struggle to raise revenue from ticket sales if their licence limits the hours when they can play live music.

Some groups can face greater licensing scrutiny than others. One example of this is Form 696, a risk assessment form introduced by the Metropolitan Police in 2005 that required promoters to give information about the music genres and audience ethnicity of their club nights. The form was required for events that featured DJs and MCs, targeting predominantly Black-led music genres.

In 2009, questions asking for the telephone numbers of acts, the music genres and the audience ethnicity were removed. Although the form was officially scrapped in 2017, event organisers from underrepresented backgrounds report that they still often face heavy scrutiny from venue operators. This includes questions about the acts they are hiring, and requirements to pay for additional security services.

Licensed premises led by underrepresented groups can also face greater scrutiny from licensing authorities. One example is where licensing officers have conducted intensive crackdowns on shisha lounges’ smoking activities, without recognising the role that such spaces play as live music venues.

Overall, licensing authorities and policing tend to approach live entertainment and licensed premises from a risk assessment perspective, instead of an economic or cultural development perspective. This approach negatively impacts groups that authorities perceive to create more risk. It has also contributed to the low levels of trust in policing services cited in the Casey Report,Reference:35 particularly among Black and LGBTQ+ Londoners. Underrepresented groups involved in leading venues or events criticise inconsistencies in how authorities and operators apply licensing and risk assessment rules, which raise additional barriers to their operations.

What organisations have told us about their experience

- A night time venue operator that was struggling to attract their usual content branched out with six new events over 18 months. This triggered a visit by licensing police officers. The operators’s licensing consultant joined the visits. During the visits, the police indicated that they would not support certain types of music and the inclusion of certain types of music could lead to a review of the licence. Details of the proposed events, including risk assessments, were provided to the police, alongside details of the DJs. The police indicated that they would prefer no events of the proposed type. They also suggested that they would have insisted on weapons arches, increased security and drugs boxes as additional mitigations to any existing licensing conditions if they had anticipated the operator would pivot like this. The venue’s overarching owner was in full support of the events and their own licensing adviser confirmed that the operator would be complying with both the Licensing Act 2003 and the Equality Act at all times. The venue operator is now not programming the proposed type of events.

Barriers increasing this risk

- Venues led by and serving underrepresented groups, including Black groups, face increased scrutiny within the licensing system. They also have greater requirements placed on them to run events during late-night hours.Reference:36

- Local authority officers may be unfamiliar with the cultures represented in a space and the needs of those served by these spaces. An example of this is applying Sexual Entertainment Venue licensing requirements to alternative LGBTQ+ entertainment events.

- A lack of transparency in the licensing process, and the complexity of the licensing system, can prevent organisations from getting the licences they need, or from appealing licensing refusals.

Good practice

Helping night-time economy businesses navigate licensing and other regulations

Significant opportunity exists in London to become part of the night-time economy. Certain barriers can prevent entrepreneurs and businesses from creating a night-time offer, such as security concerns, information overload, unknown logistics, and a lack of existing local evening hubs or attractions.

Entrepreneurs and businesses come in all shapes and sizes, from private companies and limited partnerships to community organisations, sole traders and charities.

The Night Time Enterprise Zone Toolkit (NTEZT) brings together licensing, environmental health, trading standards and planning regulation guidance in one place. And explores key considerations and regulations for those looking to offer evening or night-time activities.

Read case study: Helping night-time economy businesses navigate licensing and other regulations

Recommendations

- Local licensing authorities can share best practice on supporting community-led and cultural organisations through licensing processes.

- Local licensing authorities can ensure that licensing officers understand the potential impacts of systemic historic inequality, the low level of trust towards public authorities in some communities, and unconscious bias by decision-makers on licensing decisions.

- Local licensing authorities can monitor and report on the impact of licensing policies and decisions on community-led and cultural spaces, especially those led by or serving underrepresented groups.

4.4 Underlying condition: Funding reductions and funding design

Austerity measures in recent years have significantly impacted funding and resources for local authorities and other public-sector organisations. Between 2010 and 2019, local authority spending fell by 35 per cent in real terms.Reference:37 The impact of council funding cuts continues to threaten community-led and cultural spaces. For example, funding cuts to local authorities have lowered investment in the physical maintenance of council-owned assets. Many organisations in council-owned spaces are working in outdated buildings or taking on the cost of carrying out repairs. Reductions in central government funding for local authorities can also lead to increased rents, as local authorities seek to generate more income to deliver core and statutory services.

Budget pressures have changed local authorities’ ability to retain council-owned properties. As London’s land values increase, local authorities have sold council-owned property to meet increasing financial pressures to deliver their core services with less funding. A 2018 study found that, since 2012, London’s council-owned assets had been sold at a rate of over 200 per year.Reference:38 Recent inflation and maintenance cost increases have increased this pressure on councils, leading some to put major buildings up for sale in efforts to avoid bankruptcy.

Previous government policies have redirected significant levels of funding away from the capital. London’s share of National Portfolio Organisation grants distributed by Arts Council England fell from 46 per cent to 40 per cent in the 2018 to 2022 funding round, and to 32 per cent for the 2023 to 2026 funding round.Reference:39 In addition, Arts Council England has made funds available for organisations to move outside London. This severely weakens the funding landscape for cultural and community organisations.

Restricted funding overall means there is increased competition for funds between organisations. This in turn increases the financial precarity of community-led and cultural organisations, on top of the burdens caused by cost and rent increases. As well as these limitations, it has become more difficult for groups to secure long-term funding agreements and core funding. An increasing proportion of the remaining funding is offered for one-off projects, rather than long-term initiatives.

Short-term, project-based funding requires organisations to devote staff resources to pursuing the next short-term funding opportunity and reporting on funding. This creates financial uncertainty for organisations and risks to their long-term survival. A briefing by research charity IVAR highlights that a funder preference for project-based funding can result in many charities not spending enough on overhead costs.Reference:40

Even where funding is intended to provide long-term certainty, its design and delivery can limit its success in reaching all communities. Funding must explicitly respond to the needs of underrepresented groups to address the barriers they face. For example, the Community Ownership Fund was a welcome step towards increasing community ownership of assets. However, the funding available did not reflect the higher funding needs for London’s context and the delivery speed required did not account for the capacity of community groups. Also, the funding did not require delivery partners to conduct outreach to underrepresented groups. This limited the fund’s ability to address inequalities in access to community ownership. In response to stakeholder and applicant feedback, the previous government extended the maximum capital funding available to new applicants up to £2m.Reference:41

Innovative approaches from funders to addressing historic inequalities are emerging. In July 2023, charitable grant-making foundation Lankelly Chase announced its plan to redistribute all its assets and close within five years. Lankelly Chase will give £8m (around 6 per cent of its total endowment fund) to the Baobab Foundation, an organisation working to support, grow and strengthen the work of Black and global majority communities.Reference:42 Recognising intersectionality between race and poverty in the UK, Trust for London and City Bridge Trust launched a £4m racial justice fund aimed at increasing economic empowerment among London’s Black and minoritised communities.Reference:43

What organisations have told us about their experience

- A community centre supporting young Londoners from marginalised backgrounds operates out of a space leased from the local authority. The building needs investment. The organisation has been successful in accessing different funds for projects working with young people. However, a lack of core funding makes it difficult to grow and invest in its delivery space. The organisation is ambitious and continues to support young people with their own enterprises – something they are experienced at, and trusted in doing. But the challenge of building up financial resilience, along with a lack of available suitable space, is making service delivery difficult.

- A cultural and community centre serving the Indian community in London has been struggling with the cost of mortgage payments. To meet the high demand for its services, the organisation obtained planning permission to build an additional floor in its centre, and would like to hire more staff. However, due to the lack of sustainable core funding, the organisation is unable to expand its services and improve its space.

- A women-led training and development co-operative that works with ethnically diverse and marginalised local women is based on the ground floor of a modern student housing block. The surrounding area is experiencing significant change, driving up rents. Rent now makes up an increasingly significant part of the co-operative’s costs. At the same time, it cannot secure core funding and relies on project funding. This limits its ability to recover ever-rising overheads, while making project delivery more expensive and less competitive.

- An organisation providing support, advice and training to racialised communities (including employment-related courses, help with housing and benefits, and interpreting services) operates across several inner London boroughs. For ten years, it has operated from a privately rented shop unit, paying commercial rent. The organisation is continuously fundraising to cover the rent. The property owner has provided some flexibility on rent payment, but the organisation is finding it difficult due to cashflow challenges. The constant focus on fundraising means the organisation cannot plan effectively, nor concentrate on delivering services to those relying on them.

Barriers increasing this risk

- Organisations led by underrepresented groups have, historically, less access to financial resources, and are more financially precarious. For example, voluntary and community sector organisations serving Black, Asian and minority ethnic people, on average, receive about half the sector-average funding levels.Reference:44

- Many funding applications use and require complex language that privileges organisations that have bid-writing expertise; can afford grant-writing consultants; or have long-standing relationships with funders.Reference:45

- Underrepresented groups operating spaces that provide services for those most impacted by the pandemic, and the cost-of-living crisis, experience an increased demand for these services, while needing to continuously fundraise.

- Underrepresented groups running community-led and cultural spaces often have less financial and staff capacity to invest in fundraising and to cover rising rents. They require funding for core costs to plan effectively - but often can only access restricted, short-term, project-based funding.

Good practice

Delivering equity in grant making

Making the application process equitable was a key consideration when designing the GLA’s £1m Untold Stories fund, part of the Commission for Diversity in the Public Realm.

The fund helps communities test, develop, create and grow projects that share their community’s stories with the city.

The GLA worked with inclusion partners Ubele Initiative, the Women’s Resource Centre and LGBT Consortium, which extended the fund’s reach. The inclusion partners helped the GLA by tapping into new networks and providing practical support on completing applications.

Recommendations

- Funders, including the GLA group, can consider how they can use their investment to address long-standing barriers to accessing space faced by underrepresented groups. This includes the provision of longer-term, less restrictive funding or endowments.

- Funders, including the GLA group, can recognise and address the potential impacts of systemic historic inequality, application process design, applicant capacity and unconscious bias by decision-makers on investment decisions.

- Funders, including the GLA group, can consider engaging with the London Funders network and resources to learn from, and share, best practice on grant-making.

4.5 Underlying condition: Networks and relationships

Community-led and cultural organisations work within a network of relationships. Typically, key stakeholders include:

- local authorities

- other public-sector bodies – for example, the NHS and Arts Council England

- multiplier organisations

- sector-specific network organisations

- property owners

- academia

- funders.

Having strong existing relationships with these stakeholders are mutually beneficial. For example, local authorities could see organisations as potential delivery partners, and organisations could help local authorities connect to local community groups and disseminate vital information. Property owners could see organisations as valued tenants who they can negotiate flexible arrangements with during times of financial stress. Strong relationships with funding bodies can also help organisations gain more security over long-term funding.

However, having underdeveloped or tense relationships with key stakeholders can create problems for community-led and cultural organisations. Lacking relationships with local authorities can mean council officers are unaware of a community space’s existence, or of the important services provided from spaces. This could lead the community to be left out of decision-making. Tense relationships with property owners can limit organisations’ ability to negotiate favourable lease terms, and can put organisations at risk of eviction if property owners are unwilling to grant flexibility. Lack of relationships with funders can make it more difficult for organisations to succeed in grant application awards.

What organisations have told us about their experience

- A community centre serving Londoners of Chinese heritage wants to expand its service offer and move to a new, bigger space to respond to a growing demand from the community. The organisation has been working with the local authority to undertake a community asset transfer. The process has been hampered by having to navigate multiple departments, provide the same information multiple times and build new relationships due to staff turnover.

- A faith group running a foodbank operates out of a building owned by a local authority. The local authority transferred the building to a housing association on a long-term lease, which then commissioned an asset management company to manage sub-lets. The complex nature of the lease arrangements makes it more difficult for the faith group to make a case for lower rent – one that recognises the social value they deliver. The organisation pays rent at a higher rate compared to other spaces paid for by community organisations in the borough.

- The boundaries between business and community activism can be blurred, especially within the more commercial parts of the creative sector. A north London centre for the UK’s pan-African community blends publishing, bookshop and community activities. The property is privately owned by the publisher, who wishes to establish a community-owned and managed space for future generations. The owner has set up a community interest company, with others, to progress their ambitious plans for a purpose-built centre. The organisation wishes to engage with local and regional government, but finds it difficult to understand how they could be supported by, and how to navigate, complex government organisations.

Barriers increasing this risk

- Limited representation on the boards of funding bodies and within local authority leadership roles.

- Limited relationships with property owners, meaning organisations lack influence over management decisions that affect their space. This, combined with a lack of visibility to local authorities and other key stakeholders, can lead to decisions that negatively impact organisations.

- Low levels of trust in local authorities and other public-sector bodies due to historical decisions or previous experiences of discrimination.

- Capacity challenges within local authorities, leading to high staff turnover and loss of institutional knowledge and relationships.

- Capacity challenges within organisations, leading to a lack of time and resources to build, maintain and manage relationships with key stakeholders.

- Lack of continued support, investment and capacity-building following on from councils’ historic engagement with communities of interest – for example difficulties securing long-term lease renewals for Black-led community centres established in the 1980s.

Good practice

Skills and resource sharing with organisations

The Skills Forum was a day of workshops run by the Mayor of London’s Culture and Community Spaces at Risk programme, which brought together 30 of London’s at-risk organisations.

The workshops were a mixture of peer-to-peer learning and subject matter experts, including planning officers, development managers, governance experts and communications professionals. The Skills Forum was an opportunity for organisations to gain new skills, share insights and network. Culture and community spaces in north London often face the same challenges as organisations in south London, but they aren’t aware of each other.

Read case study: Skills and resource sharing with organisations

Building alliances to secure space together

The African Educational Cultural Health Organisation (AECHO), formed in 2003, is a charitable organisation based in Merton. It aims to assist people of African descent, and other minority ethnic communities, offering training in basic skills, citizenship, identity, diversity, enterprise, parenting and counselling. It also runs projects promoting community cohesion. AECHO wishes to manage its own space in future, with greater tenure security. Recognising significant space competition, AECHO has formed an alliance with other likeminded organisations, advocating for space while potentially finding shared space for alliance members.

Read case study: Building alliances to secure space together

Strategic relationship building to secure space in a prime location

Croydon BME Forum is an umbrella organisation, supporting Black and minority ethnic voluntary sectors in Croydon. Established in 2003, it provides specialist infrastructure support (including community engagement and capacity building), and manages the Croydon Wellness Centre. It has a physical and digital space in the Whitgift Shopping Centre – an excellent location due to shopping footfall and good transport links. It is a one-stop shop for Black and minority ethnic community health and wellbeing services.

The organisation has developed good negotiation skills, and long-lease management expertise – using both to forge a strong working relationship with the shopping centre landlord. Alongside this are strategic local authority and NHS partnerships (both funders of the space). Croydon BME Forum now hopes to establish a second health and wellbeing hub, in another part of the borough.

Read case study: Strategic relationship building to secure space in a prime location

Recommendations

- Community-led and cultural organisations can proactively assess the risks that may arise and lead to a loss of space. By doing so, they can identify issues that may need external help.

- Community-led and cultural organisations can use existing opportunities, and develop new ones, to network with peer organisations and key stakeholders to share best practice and local insights.

5. Summary of recommendations

Underlying condition: Land value and increases in business rates

-

Public-sector bodies, including the GLA group, can ensure that Community Asset Transfer policies are underpinned by support and guidance for community-led and cultural organisations to successfully conduct the process.

-

Local authorities, the GLA group and other public-sector bodies can – when acting as property owners – seek to offer secure, long-term leases to community-led and cultural organisations, considering social value, equity, and long-term sustainability and income-generation capacity. In doing so they can be mindful of, and address, historic inequalities in securing space faced by underrepresented groups.

-

Local authorities, the GLA group and other public sector bodies can adopt the highest quality co-production methods in the development of asset strategies and redevelopment proposals for their own property portfolios.

-

Trusts and foundations can introduce funding streams that allow organisations led by underrepresented groups to access the legal and property expertise often required to apply for larger grants.

Underlying condition: National planning system

-

Local planning authorities can include, in their Local Plans, specific protections for community-led and cultural spaces led by or serving underrepresented groups. As an example, the Camden Local Plan states: “The Council will … ensure existing community facilities are retained recognising their benefit to the community, including protected groups.”Reference:46

-

Local planning authorities can ensure that infrastructure mapping and infrastructure delivery planning includes community-led and cultural spaces led by and serving underrepresented groups.Reference:47

-

Local planning authorities can employ co-designed and participatory research methods working with underrepresented groups to identify community-led and cultural spaces that serve these groups.

-

Local planning authorities can develop specific targets and actions for actively involving underrepresented groups when developing planning policy.

-

Local planning authorities can consider Article 4 Directions to remove permitted development rights that place community-led and cultural spaces at risk, recognising that community-led and cultural spaces may occupy properties with different use classes.

-

Central government can consider developing guidance on cultural and community infrastructure mapping and planning.

Underlying condition: Licensing restrictions

-

Local licensing authorities can share best practice on supporting community-led and cultural organisations through licensing processes.

-

Local licensing authorities can ensure that licensing officers understand the potential impacts of systemic historic inequality, the low level of trust towards public authorities in some communities, and unconscious bias by decision-makers on licensing decisions.

-

Local licensing authorities can monitor and report on the impact of licensing policies and decisions on community-led and cultural spaces, especially those led by or serving underrepresented groups.

Underlying condition: Funding reductions and funding design

-

Funders, including the GLA group, can consider how they can use their investment to address long-standing barriers to accessing space faced by underrepresented groups. This includes the provision of longer-term, less restrictive funding or endowments.

-

Funders, including the GLA group, can recognise and address the potential impacts of systemic historic inequality, application process design, applicant capacity and unconscious bias by decision-makers on investment decisions.

-

Funders, including the GLA group, can consider engaging with the London Funders network and resources to learn from, and share, best practice on grant-making.

Underlying condition: Networks and relationships

-

Community-led and cultural organisations can proactively assess the risks that may arise and lead to a loss of space. By doing so, they can identify issues that may need external help.

-

Community-led and cultural organisations can use existing opportunities, and develop new ones, to network with peer organisations and key stakeholders to share best practice and local insights.

6. Contributors and thanks

Consultant team

- Annabel Osborne, Locality

- David Moynihan, Locality

- Ed Wallis, Locality

- Stephen Rolph, Locality

- Karl Murray, The Ubele Initiative

- Saphia Youssef, The Ubele Initiative

- Yvonne Field, The Ubele Initiative

- Celine Lessard, independent researcher

Steering Group 1 – cultural and community organisations

- Account3

- AECHO

- The Africa Centre

- Brent Indian Association

- Camberwell After School Project

- Communities Welfare Network

- Golden Opportunity Skills and Development

- House of Rainbow CIC

- Maa Maat Community Centre

Steering Group 2 – representatives from policy organisations

- James Parkinson, GLA

- Ellie Howard, GLA

- Malene Bratlie, London Funders

- Alisha Pomells, London Funders

- Yolande Burgess, London Councils

- Poppy Thomas, London Borough of Haringey

- Annais Nourry, London Borough of Haringey

- Hannah S, London Plus

GLA Client Team

- Arman Nouri, Culture and Creative Industries and 24 hour London

- Joanna Kozak, Culture and Creative Industries and 24 hour London

- Mohamed-Zain Dada, Culture and Creative Industries and 24 hour London

- Phil Tulba, Culture and Community Spaces at Risk programme consultant

- Raja Moussaoui, Culture and Creative Industries and 24 hour London

Copyright

Greater London Authority 2024

Published by

Greater London Authority

www.london.gov.uk

The team would like to thank all the organisations who contributed their time and expertise as part of this research.

7. Appendix 1

Below is a summary of Mayoral policies working to protect, sustain and grow London’s valued cultural and social infrastructure.

Policy HC5: Supporting London’s culture and creative industries.

The continued growth and evolution of London’s diverse cultural facilities and creative industries is supported.

Development Plans and development proposals should:

1. protect existing cultural venues, facilities and uses where appropriate and support the development of new cultural venues in town centres and places with good public transport connectivity. To support this, boroughs are encouraged to develop an understanding of the existing cultural offer in their areas, evaluate what is unique or important to residents, workers and visitors and develop policies to protect those cultural assets and community spaces.

Policy S1: Developing London’s Social Infrastructure

A. When preparing Development Plans, boroughs should ensure the social infrastructure needs of London’s diverse communities are met, informed by a needs assessment of social infrastructure.

C. Development proposals that provide high quality, inclusive social infrastructure that addresses a local or strategic need and supports service delivery strategies should be supported.

Policy D1: London’s Form, Character and Capacity for Growth

Boroughs should undertake area assessments to define the characteristics, qualities and value of different places within the plan area to develop an understanding of different areas’ capacity for growth. Area assessments should cover the elements listed below:

1. demographic make-up and socio-economic data (such as Indices of Multiple Deprivation, health and wellbeing indicators, population density, employment data, educational qualifications, crime statistics)

7. historical evolution and heritage assets (including an assessment of their significance and contribution to local character)

Good Growth means safeguarding the unique character of local neighbourhoods. It means balancing the new and the old and ensuring new buildings do not shut down existing cultural facilities.

The Mayor calls on local authorities, community groups, architects, planning agents and developers to:

-

work with his office when matters arise and have a designated local Culture at Risk contact within the local authority

-

work in a joined-up way across planning and licensing

-

ensure existing infrastructure is considered within developments and planning application assessments and apply the draft new London Plan policies to protect existing uses

-

use the option of applying the Asset of Community Value designation to cultural infrastructure

-

apply targeted Article 4 Directions to protect against further losses

-

reduce commercial risks for cultural tenants, for example through affordable rent levels and business rate relief where appropriate.

Social infrastructure covers a range of services and facilities that meet local and strategic needs and contribute towards a good quality of life, facilitating new and supporting existing relationships, encouraging participation and civic action, overcoming barriers and mitigating inequalities, and together contributing to resilient communities. Alongside more formal provision of services, there are informal networks and community support that play an important role in the lives of Londoners

Areas of Action

Accessibility: A range of accessible and affordable social infrastructure is needed in a neighbourhood. The needs of groups that may be excluded by spatial, social, or financial constraints must be considered sensitively. These barriers to access should be included in assessments of local needs and provision.

Inclusivity: The audience that spaces and services are catering to must be considered as well as whether needs are being met across different groups. It is not necessary for all spaces to deliver all functions to all people, however within a local ecosystem of social infrastructure, the needs of all parts of the local community should be met.

Safety: Some groups within the local community need safe spaces outside the home and it is important that this is available in the local ecosystem. Vulnerable groups may need particular spaces to feel safe.

In addition to these policies, the Mayor has a dedicated team within his Culture and Creative Industries unit to protect and grow cultural infrastructure. The Making Space for Culture team delivers a suite of programmes aimed at achieving this goal.

References

- Reference:1Mayor of London, Good Growth by Design: Connective Social Infrastructure, 2020, p.72

- Reference:2Parliament of the United Kingdom, Equality Act 2010

- Reference:3Mayor of London, Good Growth By Design Handbook: Supporting Diversity, 2021

- Reference:4Australia International Council on Monuments and Sites, The Burra Charter, 2013

- Reference:5Historic England, Conservation Principles, Policies and Guidance, 2008

- Reference:6Mayor of London, Inclusive London: The Mayor’s Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Strategy, 2018

- Reference:7GLA Intelligence: London Datastore, Economic Fairness: Labour Market, 2021

- Reference:8GLA, The London Health Inequalities Strategy, 2018

- Reference:9Trust for London, London’s Poverty Profile 2022: COVID-19 and poverty in London, 2022

- Reference:10Runnymede Trust and the Centre for Labour and Social Studies, We are Ghosts: Race, Class and Institutional Prejudice, 2019

- Reference:11Ibid.

- Reference:12Department for Communities and Local Government, Ethnic Minority Business and Access to Finance, 2013

- Reference:13Centre for Research in Ethnic Minority Entrepreneurship, Time to Change: A Blueprint for Advancing the UK’s Ethnic Minority Businesses, 2022

- Reference:14Guy Shrubsole, Who owns England?: How we lost our green and pleasant land, and how to take it back, London: William Collins.

- Reference:15Ben Campkin and Laura Marshall, LGBTQ+ Cultural Infrastructure in London: Night Venues, 2006–present, 2017

- Reference:16Mayor of London and WMT Urban Research Unit, Cultural Spaces Health Check, 2023

- Reference:17We use the term ‘diverse’ to describe an organisation where 51 per cent or more of its leadership (for example, board and senior management) identify as women, people with disabilities, members of the LGBTQ+ community, belonging to an ethnic minority, or sharing other protected characteristic

- Reference:18The British Academy, Shaping the Covid Decade: Addressing the long-term societal impacts of COVID-19, 2021

- Reference:19Caroline Macfarland, Matilda Agace and Chris Hayes, Creativity, Culture and Connection. Responses from arts and culture organisations in the COVID-19 crisis, 2020

- Reference:20Kevin Fenton/UK Health Security Agency, Tackling London’s ongoing Covid-19 health inequalities, 2021

- Reference:21GLA, Health Inequalities Strategy Implementation Plan 2021-24, 2021

- Reference:22Matthew Oakley et al/WPI Economics, Inequality and Poverty in Central London before and during the Covid-19 pandemic, 2021

- Reference:23Karl Murray/The Ubele Initiative, Impact of COVID-19 on the BAME community and voluntary sector: Final report of the research conducted between 19 March and 4 April 2020, 2020

- Reference:24Race Equality Foundation, Coronavirus (Covid-19) and how it affects Black, Asian and minority ethnic people and communities, 2020

- Reference:25GLA and WMT Urban Research Unit, Cultural Spaces Health Check, 2023

- Reference:26The Guardian, 9% rise in London properties owned by offshore firms, 26 May 2016

- Reference:27Community Asset Transfer is ‘an established mechanism used to enable the community ownership and management of publicly owned land and buildings.’ See: My Community, Understanding Community Asset Transfer, 13 May 2020